SIGIRIYA city , palace , gardens monasteries, paintings

- ADMIN

- Aug 8, 2021

- 48 min read

Updated: Aug 28, 2021

Senake Bandaranayake

CONTENTS

Plan of Sigiriya 6

Sigiriya - World Heritage city 9

Historical periods 12

Urban form 16

Inner and outer city 18

Royal gardens 23

Water gardens 23

Moated palaces 24

Miniature water garden 26

Citadel and monastery 28

Boulder gardens 30

Terrace gardens 33

The climb to the summit 34

Mirror wall 35

Lion staircase 37

Paintings and poems 38

Meaning and style 42

Boulder garden paintings 46

Graffiti poems 48

Palace 51

Archaeological finds 53

Souvenir sculptures-‘Art about art’ 55

The Sigiriya earring 58

Inscriptions 59

Cultural landscape: the Sigiriya hinterland 62

Pidurangala and Ramakale 65

Environment and bio-diversity 67

Acknowledgements 70

SIGIRIYA-WORLD HERITAGE CITY

One of Asia’s major archaeological sites, the World Heritage city and palace at Sigiriya (the ‘Lion Mountain’) are a unique combination of 5th century urban planning, architecture, engineering, hydraulics, garden design, painting, sculpture and poetry. It has attracted the attention of modem antiquarians and archaeologists since the early 19th century and from the 1890s has been the subject of intense archaeological activity.

How this book is arranged

After a brief introduction to the site, its history (page 10), general plan and urban layout (page 16), the main features at Sigiriya are described in the order that the visitor would follow when entering from the Western Entrance or the Southern Gate. The sequence is as follows:

1. Ramparts, moats and gateways - page 20

2. Water gardens and moated palaces - page 23

3. Inner citadel wall and monastery complex - page 28

4. Boulder and terrace gardens - page 30 (The paintings in the boulder gardens are described on pages 46-47.)

5. Mirror wall gallery - page 35 (The paintings above the mirror wall and the graffiti poems are described on pages 38-45 and 48.)

6. Lion staircase terrace -page 37 7. Palace on the summit - page 51

There are also short sections on archaeological finds (page 53), souvenir sculptures (page 55), the Sigiriya earring (page 58), ins criptions (page 59) and the Sigiriya hinterland (page 62).

Surrounded by forests and set in a cultural landscape of remarkable natural beauty and historic interest, the ancient city, palace and garden complex is centred on the Sigiriya rock, an inselberg rising aboutl 80 metres (600 feet) above the surrounding plain. The site itself goes back to pre- and proto-historic times. The area around the main Sigiriya rock was the location of a Buddhist rock-shelter monastery from the last few centuries BC. The present city, palace and garden remains date from the time of their creator, Kasyapa 1 (477-495 AC). Opposite page'. Fig. 2 Inner moat (from north-west comer)

HISTORY

The history of Sigiriya extends from prehistoric times to the 17th and 18th centuries. Excavations in rock-shelters and the investigation of open air sites in and around Sigiriya have yielded stone and bone tools and human and faunal remains from the prehistoric period. The earliest evidence of human habitation within the environs of the main rock is in the Aligala rock-shelter, which lies immediately to the east of the Sigiriya rock. This is a major prehistoric site with an occupational sequence starting nearly 5000 years ago and extending up to early historic times. It is also one of the sites associated with early iron production in Sri Lanka, dating from around 900 BC.

The use of iron is one of the key technologies connected with the proto- historic transition from itinerant food gathering and hunting to village settlement, agriculture - especially the cultivation of millet and rice - and irrigation. The earliest monuments in the Sigiriya region are megalithic cemetery sites, one example of which is Ibbankatuva, near Dambulla. They provide evidence of the presence of early farming and iron producing communities in Sigiriya and its environs, from about 1000 BC onwards.

The historical period at Sigiriya begins about the 3rd century BC with the establishment of a Buddhist monastic settlement on the rock-strewn western and northern slopes around the base of the rock. As in other similar sites of this period, partially man-made rock-shelters or ‘caves’, with deeply incised protective grooves or drip-ledges, were created in the bases of several large boulders. There are altogether 30 such shelters at Sigiriya. Several are dated to a period between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC by the donatory inscriptions carved in the rock face near their drip-ledges. The inscriptions record the granting of these caves to the Buddhist monastic order to be used as residences.

Starting from its proto-historic origins, the Sigiriya region was to become one of the major centres of iron production in Sri Lanka in the early historic period, especially between the 1st and 4th centuries AC. Also dating from this time is the construction of the Mapagala fortified complex, with its ‘cyclopean’ walls made of massive stone blocks, the first expression of large-scale architectural construction at Sigiriya.

Kasyapa I (477-495AC)

Sigiriya comes dramatically, if tragically, into the political history of Sri Lanka in the last quarter of the 5th century during the reign of King Dhatusena I (459 - 477) who ruled from the ancient capital at Anuradhapura. A palace coup by Prince Kasyapa, the king’s son by a non-royal consort, and Migara, the king’s nephew and army commander, led to the seizure of the throne and ultimately to the execution of Dhatusena. Kasyapa, much reviled for his patricide, established a new capital at Sigiriya, while the crown prince, his half-brother Moggallana, went into exile in India. The chronicles ascribe a period of 18 years to Kasyapa’s reign, calculated by historians to extend from 477 to 495, although it is possible that he ruled for a somewhat longer period. The king and his master-builders gave the site its present name, ‘Simha-giri’ or ‘Lion-Mountain’, and were re sponsible for most of the structures and the complex plan that we see at Sigiriya today. His reign came to an end with the return of Moggallana, and Kasyapa’s defeat and suicide on the battlefield.

Sigiriya after Kasyapa

This brief Kasyapa episode was in fact the golden age of Sigiriya. In the post- Kasyapa period, Sigiriya reverted to being a monastic centre. Monasteries were located within the Inner Citadel area, and in the neighbouring sites of Pidurangala and Ramakale. The innermost royal precincts, consisting of the palace itself and the access to the summit, seem to have been little used or, more likely, abandoned. The city and its suburbs, however, continued to be occupied, and visitors to the city climbed the rock to view the paintings, the Lion Staircase and the palace.

This epoch lasts till about the 13th or 14th century, after which Sigiriya disappears for a time from the history of Sri Lanka. It appears again, first in the reign of Rajasimha I of Sitavaka (1551-93) and then as a distant outpost and military centre of the Kingdom of Kandy, in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Modern recovery

The city’s name, location and royal connections were never forgotten, but it had reverted to being a small village settlement until the early 19th century when antiquarians, including a scholar monk from the neighbouring temple at Pidurangala, began to take an interest in the site.

They were followed several decades later by archaeologists, who have now been working there in research and conservation programs, for over 100 years, since the 1890s. Successive Commissioners of the«Archaeological Department were responsible for directing research, restoration and conservation over the decades. Major contributions were by H.C.P. Bell (mainly from 1894 to 1900, who restores the access to the palace, excavates the summit and maps the entire complex) and Senarat Paranavitana (1930s and1946-54; the doyen of Sri Lankan archaeology, who deciphers the graffiti, identifies and excavates the Water Gardens and the ' western sector, and re-interprets the paintings and the site)

The Central Cultural Fund’s wide spectrum Cultural Triangle heritage management program began work at Sigiriya in 1982. This involved the first large-scale, controlled, stratigraphic excavations at the site and extensive conservation and preservation action. It focused attention not only on the best- known and most striking aspects of Sigiriya - the royal complex of rock, palace, gardens and the western fortifications - but also on the entire city and its rural hinterland. Archaeological direction and multi-disciplinary team research were bv the University of Kelaniya Archaeological Team and, later, the university s Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology (PGIAR). A ‘total archaeological landscape’ survey was initiated in 1988.

HISTORICAL PERIODS

Sigiriya as we see it today is essentially the creation of Kasyapa I (477-495 AC) and his master-builders, but the site has a many layered history. Over the millennia it has undergone many transformations due to both natural and human activity. The geological origins of the Sigiriya rock go back to Middle Pre Cambrian times, between 3500 and 2000 million years ago. At present, the first traces of human activity are from about 5000 BC. The main rock itself was first occupied during Kasyapa’s reign. As the chronicles record, he shifted the capital from the ancient city of Anuradhapura to Sigiriya, and built the palace on the summit, laying out the fortified city and garden complex around the rock. However, the site has a rich pre-Kasyapa and post- Kasyapa history which has been reconstructed by archaeological investigation, including the most recent research over a 20-year period under the Central Cultural Fund’s Cultural Triangle program. The transformations at Sigiriya cover at least twelve distinct periods of human activity. These provide a working periodisation that can be summarised in the following way :

Period 1: Prehistory.

Sigiriya and the surrounding area were probably occupicdby prehistoric humans from between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago, although the earliest dates available from present investigations go back to about 5000 BC.

Period 2: Proto-history.

Significant developments took place in the Sigiriya region during the proto-historic transformation. This involved a fundamental change from itinerant food gathering and hunting to agriculture - especially the cultivation of millet and rice - village settlement, irrigation and the production and use of iron, during the period between about 1000 and 300 BC.

Period 3: Early monastic.

History begins from about the 3rd century BC. This is marked by the establishment and proliferation of early Buddhist monastic settlements dating from the 3rd to the 1 st century BC. These developed around rock-shelter residences with donatory inscriptions recording the granting of these shelters to the Buddhist monastic order.

Period 4: Pre-Kasyapa.

The period between the 1st and 5th centuries AC sees the development of large-scale iron production in the area around Sigiriya, and the construction of the fortified Mapagala complex, with its ‘cyclopean’ walls and terraces, located immediately to the south of the Sigiriya rock. Settlement sites from this period have been found on the slopes around the rock itself and in the immediate vicinity of Sigiriya.

Period 5: Kasyapa I (477-495AC).

This is the major construction phase at Sigiriya. The dates for Kasyapa’s reign are approximate ones, based on the chronicles. He may well have ruled for a longer period, although the material and managerial resources he could command had the potential to construct what we see at Sigiriya today during a reign of 18 years. Nearly two decades of extensive excavation and research since 1982, have given clear evidence of many sub-phases of construction during the overall Kasyapa phase - and also indicate that the complex.was not completed when this major construction effort came to an end.

Period 6: Later Monastic A.

The first phase of the later monastery period, from the 6th to the early 8th century, sees the foundation of a new Buddhist monastery in the western sector and the Boulder Garden area. It also sees new developments in the monastery at Pidurangala and probably the foundation of the Ramakale monastery to the south. Technologically, the period is marked by the beginnings of the use of dressed gneissic-granites in building construction. The urban complex and the artistic traditions of the ‘School of Sigiriya’, both painting and terracotta sculpture, continue to flourish. The period also has sub-phases of collapse, destruction and rebuilding whose exact chronology and trajectory are yet to be firmly established. The earliest graffiti by visitors to the site date from the last years of the 5th or the early 6th century.

Period 7: Later Monastic B.

The period from about the 8th to the 10th century is characterised by similar but less clear alternation of phases of development, collapse and reconstruc tion. The monasteries of Pidurangala and Ramakale are marked by a high level of building activity. Inscriptions in the form of‘immunity grants’ indicate the power and wealth of these monasteries. The Water Gardens at Sigiriya are modified. The rock, the abandoned palace and the paintings become the focus of great visitor interest. The poetry in the graffiti often displays high literary qualities.

Period 8: Polonnaruva period.

The period from the 11th to the 13th century is coeval with the rise of Polonnaruva as a major urban centre and the political capital of the country. During this time there is clearly a decline in the construe- i tional activity of the monasteries in and around Sigiriya, ex cept in centres such as Dambulla, which enjoy royal patron age. New building technologies, however, such as the renewed and improved use of brick masonry, plaster walls and stucco mouldings, and changes in tile and pottery forms, are indi cated by surface remains and excavations at Sigiriya, Pidurangala and elsewhere in the region.

Period 9: ‘Abandonment’.

The period from about the late 13th or early 14th century to the 16th/17th century appears in the present archaeological, epigraphical and historical record as an era of abandonment of the urban and monastic centres at Sigiriya and in the Sigiriya region. The area, no doubt, continued to have its rural settlements and local irrigation systems. The last phase of Period 8 - or the first phase of Period 9 - is marked by the appearance of a final layer of paintings (sketches) in the Boulder Gardens showing an interesting ‘weakening’ of the classic realist style of the Sigiriya tradition. Excavations have shown similar modifications in garden arrangements in the Water and Boulder Gardens.

Period 10: The Kandyan kingdom.

Sigiriya and its surrounding area appear once again in the historical and archaeological record as part of an outer province of the kingdom of Kandy. It is remembered in Kandyan historical writings as one of the great urban centres of earlier times, and functions as a regional military centre and staging point in the communication network of the kingdom.

Period 11: Antiquarian interest.

The first phase in the modem recovery ofSigiriya is in the early 19th century-following renewed royal interest in the great temple at Dambulla, and the Buddhist revival of the late 18th century. Many ancient rock-shelter monasteries in the region are re-occupied. A scholar monk at Pidurangala copies the inscriptions in the area, and modem antiquarians ‘re-discover’ the site.

Period 12: Modern recovery.

Archaeological investigation, restoration and conservation work by the Archaeological Department begins in 1894. This includes major periods of activity under successive Archaeological Commissioners, notably H.C.P. Bell (mainly 1894 to 1900) and Senarat Paranavitana (mainly 1946 to 1954). Work continues from the mid- 1950s during the tenure ofC.E. Godakumbure (late 1950s, 1960s), Raja de Silva (1970s) and Roland Silva (1980s, 1990s). An entirely new phase of multi disciplinary team research and extensive preservation and conservation action begins in 1982, under the heritage management master plan of the Central Cultural Fund’s Cultural Triangle program and the archaeological direction of the University of Kelaniya and the PGIAR (Archaeological Director: Senake Bandaranayake, 1982-1999; S. Epitawatte 1999-).

THE SIGIRIYA COMPLEX

Often wrongly described as a fortress or castle, Sigiriya is in fact a well-planned royal city and a multi-faceted, multi-period settle ment, several square kilometres in extent. The entire archaeologi cal complex consists of the following elements:

1. The central core around the rock and the palace

2. The western sector - essentially the water gardens

3. The eastern sector - the inner and outer cities

4. The Mapagala fortified complex

5. The Pidurangala monastery

6. The Ramakale monastery

7. The Sigiriya lake (Sigiri Mahavava) and canal system.

Urban form

The royal complex and the city, ramparts, moats, gateways and gar dens of Sigiriya together form one of the best-preserved and most magnificent examples of ancient urban planning and palace and garden architecture in South Asia.

The remains of the palace are located on the summit of the Sigiriya rock. The rock and the palace form the centre of an elabo rate city complex, consisting of two large urban and garden zones, lying respectively to the east and west of the central core.

The original plan of the city was in the form of a regular rectan gle with five main sectors, consisting of:

(a) the palace and palace gardens on the summit of the rock, with intricate staircases and galleries leading up to it;

(b) a fortified inner royal precinct or citadel in the area around the base of the rock, which also incorporated terrace and boulder gardens and, on the highest terrace, the massive Lion Staircase leading to the gallery giving access to the summit;

(c) the inner city (or ceremonial precinct);

(d) outer city zones to the east of the royal centre, surrounded by suburban settlements outside the ramparts; and

(e)the western precinct, laid out as an extensive water gar den system with its own palace buildings and pavilions.

The city is designed on a square module, approximately 2750 metres from east to west and 925 metres from north to south. The east-west and north-south axes of the module meet at the centre of the palace on the summit. All eastern and western entrances are directly aligned with the central east-west axis, and in the western sector an ‘echo’ plan duplicates the layout on either side of east-west and north-south axes. The city is surrounded by moats and ramparts, including a double moat and triple rampart on the west.

In its total conception, Sigiriya presents a brilliant combination of symmetry and asymmetry in a deliberate interlocking of geometrical plan and natural form. It is an outstanding example of mid-first millennium planning mathematics, displaying a high degree of sensitivity to the incorporation of irregular, organic natural features in a plan based on an intricate square module.

To the south of the urban zone, as demarcated by the ramparts and moats, lies the fortified Mapagala complex, now found to pre date the Sigiriya city. Adjoining it is the city’s main reservoir, the Sigiri-vava, formed by a seven-kilometre long earth dam, fed by local precipitation and a canal system. To the north and south of Sigiriya, respectively, are the Pidurangala and Ramakale monas teries, the former predating and also contemporaneous with the royal city.

Sigiriya, like the ancient capital at Anuradhapura and the 12th century city of Polonnaruva, provides us with a clear model of a Sri Lankan royal city, with its well defined zonal divisions and many urban elements, such as the palace, royal precincts, ram parts, moats, gateways, gardens, hydraulic systems, outlying mon asteries and suburban settlements.

Inner and Outer City

Visitors to Sigiriya walk across the Water Gardens of the western sector and the Citadel and Boulder Gardens on the way to the rock and the summit. Hidden under heavy forest to the east of the rock and the Citadel extend the outlines of the Inner and Outer City.

The Inner City measures about 700 metres from east to west and 500 metres from north to south, with a high earthen rampart, gate ways and a buried moat. On a low rock outcrop in the centre of the Inner City is evidence of a pavilion, directly aligned with the east ward-oriented throne on the summit, suggesting that this area was a ceremonial precinct connected visually and symbolically with the palace on the top of the rock. Beyond this Inner City is the Outer City area, a rectangle about 1500 by 1000 metres. Excava tions and surveys in this area have also indicated suburban set tlements beyond the walls.

We still have no precise idea how these two urban zones func tioned internally, or the exact nature of their relationship with the royal citadel, the rock, the palace and pleasure gardens to the west, apart from the clear spatial zoning of the urban plan. It seems likely that this eastern area was the ‘metropolis’ of the Sigiriya complex, where the bulk of the city’s population lived-nobles, officials, traders, craftsmen, soldiers, servants and slaves.

Fig. 4 Planning module

RAMPARTS, MOATS AND GATEWAYS

The limits of the Sigiriya complex are clearly demarcated by an intricate system of moats and ramparts, lying mainly to the east and west, but also to the north and south of the rock. The best- preserved and most elaborate are those of the western precinct, which include a substantially excavated and restored inner moat and a high earth embankment with stone retaining walls forming the inner rampart.

A middle rampart extends over a substantial section of the western area. Beyond it are the outer moat and a low earth embankment or outer rampart. The total length of the ramparts around Sigiriya, excluding the stone boundary wall of the Citadel and the Mapagala fortifica tions, is about ten kilometres, while the moats, when fully plotted, may add up to nearly eight kilometres. The moats were fed by the man-made lake or reservoir, the Sigiri Vava, lying to the south of the main rock. The earth dam of this great reservoir extends from the Sigiriya rock to the Mapagala and then continues southward for another eight kilometres.

Fig. 5 Inner moat and rampart (from south-west comer)

Fig. 6 Southern entrance

It is possible today to walk the more than one kilometre length of the inner rampart, the most accessible section of which is to the right just inside the western entrance.

The inner and middle ramparts had tile-roofed walkways along their length. It is likely that the middle and outer ramparts and the outer moat were incomplete and that construction was interrupted with the sudden and dramatic termination of Kasyapa’s reign.

Three excavated and conserved entrances are found in this west ern area: the great northern and southern gateways, large enough for vehicular traffic, and the small western entrance or ‘water- gate’. The original access to this water-gate was by a causeway across the outer moat, a wide entrance in the middle rampart and probably a drawbridge across the inner moat.

ROYAL GARDENS

Sigiriya provides us with a unique and relatively little-known ex ample of what is one of the world’s oldest historic gardens, and the oldest surviving large-scale garden form in Asia, whose lay out and internal features are still in a fair state of preservation. Three distinct but inter-linked garden types are found here: water gardens, boulder gardens, and stepped or terrace gardens encir cling the rock. A combination of these three garden types is also seen on a reduced scale in the palace gardens on the summit of the rock.

Water Gardens

The Water Gardens are the most extensive and intricate garden form at Sigiriya. They occupy the central section of the western precinct. Three principle gardens lie along the central east-west axis.

Garden 1, the largest of these, consists of a central island sur rounded by water and linked to the main precinct by cardinally- oriented causeways. The quartered mandala or char bagh plan thus created constitutes a well-known ancient Asian garden form of which the Sigiriya version is the oldest surviving example. The entire garden is a walled enclosure with gateways placed at the head of each causeway. The largest of these gateways, to the west, has a triple entrance. The cavity left by the massive timber door posts indicates that it was an elaborate gatehouse of timber and brick masonry, with multiple, tiled roofs.

Garden 2, the ‘Fountain Garden’, is a narrow precinct on two levels. The lower, western half has two long deep pools with stepped cross-sections. Flowing into the pools are shallow ser pentine ‘streams’ paved with marble slabs and kerbs. Fountains, consisting of circular limestone plates with symmetrical perfora tions, punctuate these serpentines. They are fed by underground water conduits and operate on a simple principle of gravity and pressure. With the cleaning and repair of the underground con duits, in rainy weather the fountains operate even today.

Two relatively shallow limestone cisterns are placed on oppo site sides of the garden. Square in plan and carefully constructed, they may well have originally functioned as storage or pressure chambers for the serpentines and the fountains. The eastern half of the garden, which is raided above the western section, has few distinctive features: a serpentine stream and a pavilion with a lime stone throne being almost all that is visible today

Garden 3 is on a higher level and consists of an extensive area of terraces, halls and pools. In its north-eastern comer is a large oc tagonal pool and terrace at the base of a towering boulder, a theat rical juxtaposition of rock and water at the very point at which the Water Gardens and Boulder Gardens meet. A raised podium and a drip-ledge for a lean-to roof are the remains of a ‘bathing pavil ion’ on the far side of the pool. The central feature of Garden 3 is two ‘L’-shaped pools which define the area in front of the en trance to the Citadel.

These ‘L’-shaped pools are at the eastern limit of Garden 3. Be yond them are the steps of the entrance and massive brick and stone wall of the Citadel. This towering citadel wall, now reduced to less than half its original height, was once a dramatic backdrop to the Water Gardens, echoing an even more dramatic view of the great rock and the palace on its summit further to the east.

When seen from the Water Gardens, the wall extends from the tall boulder above the Octagonal Pool to a matching bastion on the south-east formed by wide brick walls, and a series of boul ders which surround a cave containing a rock-cut throne. The pools and other water-retainir.g features of the gardens were interlinked by a network of underground conduits, initially fed by the Sigiriya lake and probably connected at various points with the surrounding moats.

Moated Palaces

The three water gardens constitute a dominant series of rectangu lar enclosures of varying size and character, joined together along a central east-west axis. Moving away from this to the wider con ception of the western precinct as a whole, we see that its other significant feature is a sequence of four moated islands, at right angles to the central axis of the Water Gardens. These follow the principle of symmetrical repetition or ‘echo planning’ - the two inner islands, on the one hand, and the two outer islands, on the other, forming pairs.

Fig. 8 Inner moat and rampart

Fig 9 Cistern and vertical drain in Boulder Gardens

Fig. 10 Moated palace

Fig. 11 Fountains in Water Garden 2

The two inner islands, closely abutting the Fountain Garden on either side, are partially built up on surfacing bedrock. They are surrounded by high rubble walls and wide moats. The flat tened surface of the islands were occupied by ‘water palaces’ or ‘cool palaces’. Bridges, built or cut into the surface rock, pro vided access. Further to the north and south, almost abutting the ramparts, are the two other moated islands, still unexcavated but clearly displaying the quartered or char bagh plan.

Intricately connected with the water gardens of the western precinct are the double moat surrounding it and the great artifi cial lake extending southward from the Sigiriya rock.

Miniature Water Garden

Just inside the western entrance, to the west of Water Garden 1, is a garden very different in character from those described above. This was discovered during excavations in the 1980s. It contains at least five distinct units, each consisting of pavilions of brick and limestone surrounded by paved water pools and winding wa ter-courses. The two units at the northern and southern extremi ties are badly eroded, but the general layout of the major portion of the garden and of the three central units is clear.

A striking feature of this ‘miniature’ garden (it is in fact about 90 by 30 metres) is the use of water-surrounds with pebble or polished marble floors, covered by shallow, slowly moving water. These probably served as a cooling device, but at the same time had great aesthetic appeal, creating interesting visual effects, en hanced by the sound of moving water. In the south-eastern comer of the garden is a deep cistem for water storage. Cavities in its thick brick walls indicate that it once had a structure, probably of wood, which supported a roof or, more likely, a water-lifting device

Fig. 12 ‘Miniature’Water Garden

Another distinctive aspect of this complex is the geometrical intricacy of the garden layout. While displaying the symmetry and ‘echo-planning’ characteristic of the Sigiriya water gardens as a whole, this miniature garden has a far more complex inter play of tile-roofed buildings, water-retaining structures and wa ter-courses than is seen elsewhere in Sigiriya.

More than one phase of construction is evident here. The garden was originally laid out as an extension and ‘miniaturised’ refine ment of the main water garden macro-plan and belongs essen tially to the last quarter of the 5th century. Added to in later years and remodelled, it was subsequently abandoned and again par tially built over in the last phases of the post-Kasyapa period be tween the 10th and 13 th centuries

It is almost certain that a similar garden lies buried beneath the lawns of the unexcavated parallel sector in the northern half of the water-gardens, an ‘echo’ or ‘twin’ of this miniature garden.

Citadel and Monastery

At the eastern extremity of the Water Gardens, are the main en trance steps to the Citadel, a walled, inner, royal precinct, cover ing an area of about 15 hectares. It has a broadly elliptical plan, more or less defining the outer limits of the hill slopes around the base of the rock. This boulder-strewn hillside has been fashioned into a series of terraces, forming not only a clearly defined and protected area but also boulder and terrace gardens around the rock.

The Citadel is entered today from the Water Gardens, over the broad steps of its western entrance. (An alternative modem path way also connects it directly with the inner, southern car park.) On either side of these steps are the vestigial remains of the citadel wall. Built, like the steps themselves, of rough-hewn blocks of stone, and originally faced with brickwork and plaster, it also incorporated large natural boulders that lay in its path. The result of many phases of construction and decay, the original 5th century base of this once-towering wall (see also page 24) lay several metres below the present ground level.

Immediately inside the entrance to the Citadel is the centre of the post-Kasyapa monastery. The most prominent features here are a bodhighara, a circular temple for a sacred Bodhi tree, a rock-shelter which functioned as an image-house, and the remains of a stupa on top of a boulder. The chapter-house or uposathaghara, which at this period also functioned as the residence of the head of the monastery, is indicated today only by the rectangular out line of the building located on a high boulder, presiding over the monastic complex.

The basic 5th/6th century plan of this monastery makes it one of the earliest dated examples of a distinct monastery type, referred to in Sri Lankan archaeological terminology as a pabbata vihara. The present remains of the monastery belong to several phases of construction, dating from the late 5th or 6th century to the 12th or 13th century. The rock-shelter image-house was also originally a monastic residence of the early monastic phase in the 2nd or 3rd century BC. It is dated by a donatory inscription of that period.

Fig. 13 Monastery and western wall of Citadel

Boulder Gardens

The entrance to the Citadel and the Monastery is also the entrance to the Boulder Gardens, at their western extremity. These gardens present a design in marked contrast to the symmetry and geom etry of the Water Gardens. It is an entirely organic or asymmetri cal conception, consisting of a number of pathways which link several clusters of large natural boulders, extending from the south ern slopes of the Sigiriya hill to the northern slopes below the Lion Staircase terrace.

One of the most striking features of these gardens is their rock- associated architecture, a distinctive aspect of the ancient Sri Lankan architectural tradition. Every boulder here once had a build ing or pavilion erected on it and a painted rock-shelter below. What seem to us today like steps and drains or honeycombs of holes on the sides or tops of boulders are in fact the foundations or footings of ancient brick walls and timber columns and beams. The natural surface of the boulder was retained in the middle, between the building on top and the painted rock-shelter below.

Fig. 14 ‘Preaching Rock’

Fig. 15 ‘Audience Hall Rock’ and ‘Cistern Rock’

At several places in the Boulder Gardens are the remains of rock cut and terracotta water courses and water-retaining structures, in dicating that controlled water movement formed part of the garden architecture in this area as well. One of the most visible of these is in the complex of boulders and rock-shelters now referred to as the ‘Audience Hall Rock’ and the ‘Cistem Rock’'. These are two neigh bouring boulders, the one fashioned into an audience hall or council chamber and the other supporting a large rock-cut stone cistem or water tank, formed by massive slabs of granite.

The Audience Hall boulder has a flattened summit and a large five- metre long throne carved out of the living rock. The adjoining Cis tern Rock was originally watered by an elevated aqueduct carrying water from a large reservoir built on the south-western slopes of the hill around the great rock. The reservoir itself was designed to store water collected from the palace on the summit. After the water from the cistem was used, it was drained carefully down the side of the

Fig. 16‘Cistem Rock’ and ‘Audience Hall Rock’

Fig. 17 Boulder archway

boulder into the paved marble pathway between the two boulders. Above this pathway, a stone lintel and walls connected and prob ably provided an elevated access between the two rocks. Two other small stone seats or thrones are also found within this complex. It would appear that what we have here are two buildings used in a court ceremony involving a council chamber and a bathing ritual.

Beneath these two boulders are rock-shelters, containing several layers of fragmentary paintings. The rock-shelter below the cistern also has a large throne or altar and graffiti similar to those on the Mirror Wall.

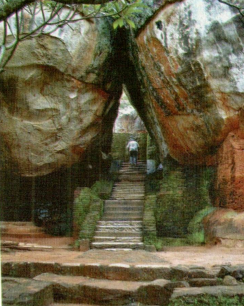

Other remarkable features in the Boulder Gardens are the two boulder archways, with their original limestone staircases, as well as various flights of steps and passageways constructed of pol ished marble blocks and slabs.

Terrace Gardens

Although there is no clear boundary between the Boulder and the Terrace Gardens, the one flowing Into the other at nearly every point, to some extent the two boulder archways mark the transi tion from the Boulder to the Terrace Gardens. The latter consti tute the third garden form at Sigiriya.

The terraces have been fashioned out of the natural hill at the base of the Sigiriya rock by the construction of a series of rubble retaining walls, each terrace rising above the other and running in roughly concentric rings around the rock. Two great brick-built staircases with limestone steps traverse the terraces on the west, connecting the pathways of the Boulder Gardens to the precipi tous sides of the main Sigiriya rock itself. In an area not as yet accessible to visitors, are the remains of a third staircase, built partly of timber, which gave access io the rock from the north. The staircases offer clear views of the terraces. It is very likely that the terraces formed the base of elaborate gardens planted with trees and flowering shrubs, but we have little idea today of their origi nal character.

THE CLIMB TO THE SUMMIT

It was with Kasyapa that the great rock - ‘difficult of ascent to humans’ as the chronicles describe it - was made accessi ble by elaborate sets of stairways and galleries from the west, the north and along the steep, precipitous sides of the rock. The two staircases, now much restored, which traverse the Terrace Gardens, meet on a landing or lobby, placed almost at the middle of the western face of the rock. This landing was once covered by a roof, evidence of which can still be seen in the beam holes cut into the rock. From this lobby, a covered ambulatory or gallery - the Mirror Wall and the marble-paved pathway it encloses - provided access across the belly of the rock to the ‘Lion Staircase Terrace’

Mirror Wall

The Mirror Wall is constructed of brick and plaster. It dates from the 5th century and has been substantially preserved in its original form. Built up from the side of the rock itself with brick masonry, the wall has a highly polished plaster finish from which it gets its ancient name, the Mirror Wall. Visible from a great distance, it is a rare and dra matic survival of the construction technique employed at Sigiriya to combine masonry and natural rock. The famous Sigiriya paintings are found in a depression high above the Mirror Wall gallery. The pol ished inner surface of the wall contains hun dreds of graffiti, de scribed on page 48 below. Frag-mentary paintings have also been found on the outer surface.

Lion Staircase

One of the most dramatic features at Sigiriya is the great Lion Staircase, now preserved only in two colossal paws and a mass of brick masonry surrounding ancient limestone steps. On the terrace in front of the lion are antechambers and courtyards forming the final reception area before the ascent to the summit. Built against the rock face, the Hon itself was a massive architectural sculpture, consisting of the head, chest and paws of a colossal sphinx-like figure. It was originally made of timber, brick and plaster and had an internal staircase. This ‘Lion-Staircase-House’, as it is called in the chronicles, was in effect the gatehouse to the solitary stairway leading to the palace on the summit. The first few flights of this stairway are the limestone steps found inside the body of the lion. The actual structure of the Lion Staircase House itself can be at least partially reconstructed from the evidence still remaining at the site.

The lion, so impressive even in its ruined state today, must have afforded a vision of grandeur and majesty when it was intact. Remarkably, we have poems recording its impact on ancient visitors to the site.

We saw at Sihigiri

the King of Lions

whose fame and splendour

remain spread

in the whole world.

Having ascended Sigiriya

to see what is (there)

I fulfilled my mind s desire

and saw

His Lordship the Lion

From another poem on the Mirror Wall which refers to ‘the face of the great lion,’ it is possible to surmise that the lion was relatively well preserved, at least until the 9th century

We know from the chronicle account of Kasyapa’s construction of Sigiriya that the Lion Staircase House was one of the principle features of his plan of the Sigiriya complex.

At the same time, it made a major symbolic statement operating on several levels of meaning, enhancing the power and majesty of royal authority and invoking ritual notions of dynastic origins, the lion being the mythical ancestor and the royal symbol of the Sri Lankan kings. Opposite page: Fig. 19 Lion Staircase

PAINTINGS AND POEMS

The most famous features of the Sigiriya complex are the 5th cen tury paintings found in a depression on the rock face more than 100 metres above ground level. Reached today by a modem spi ral staircase, they are but fragmentary survivals of an immense backdrop of paintings that once extended in a wide band across the western face of the rock and the Mirror Wall. The painted band seems to have gone as far as the north-eastern comer of the rock, covering an area nearly 140 metres long and, at its widest part, about 40 metres high. As an early writer observed: ‘The whole face of the hill appears to have been a gigantic picture gallery ... the largest picture in the world perhaps’ (John Still, Ancient Capi tals of Ceylon, Colombo, 1907:15).

Fig. 20 Western face of rock. The original painted area can be seen as a distinct ‘band’ above the Mirror Wall.

All that survive of this great painted backdrop are the female figures preserved in two adjacent depressions in the rock face

Fig. 21 Apsara

Fig. 22 ‘Fresco pockets A and B*

Twenty-two numbered figures are shown here in a drawing of 1896 by D.L.G.. Perera of the Archaeological Survey. Oil on canvas facsimiles of the paintings are now preserved in the National Museum in Colombo.

There are five figures in Pocket A’ and seventeen in Pocket B\ Of these, eighteen are clearly discernible - twelve are relatively complete and well- preserved (Al, A3, Bl, B5-15),four partly preserved (A4, A5, B2, Bl4); and two partly damaged in an act of vandalism in the 1960s (B3, B4). The rest are extremely shadowy or fragmentary (A2, Bl 5-17), one of which is only rep resented by a part of a hand. In recent times, careful scrutiny has revealed another shadowy and fragmentary figure between B2 and B3.Although the term fresco' is still commonly used in referring to th. paint ings, it is no longer believed that they really utilised the true fresco technique.

known as ‘Fresco Pocket A’ and ‘Fresco Pocket B’. (Three other depressions: Fresco Pockets C, D and E higher up the rock also contain patches of plaster and pigment and, in at least one instance, fragments of a painted figure.) Traces of plaster and pigment else where on the rock face and on the outer surface of the Mirror Wall provide further evidence of the extent of the painted band. The figures represent apsaras or celestial nymphs, a common motif in the religious and royal art of Asia.

The Sigiriya paintings have been the focus of considerable in terest and attention in both ancient and modem times. The poems in the graffiti on the Mirror Wall (discussed on page 48 below), dating from the 6th to the 13th or 14th century, are mostly ad dressed to the ladies in the paintings. The paintings also seem to have been studied and reproduced in the 18th century by the Kandyan artists who painted the great mural cycle at the World Heritage site of Dambulla nearby. Antiquarian references to the figures in the ‘fresco pocket’ date back to the 1830s. The first proper descriptions in the 19th century are based on an examina tion of the paintings by telescope from the gardens below. The first person to find his way into the fresco pocket and come face to face with the paintings in modem times was a Public Works De partment engineer C. A. Murray. He made tracings, copied them in pastel and published a paper about them in 1891

The first real study of the paintings, however, begins with the commencement of archaeological operations at Sigiriya in 1894 by H.C.P. Bell. Facsimile copies in oils were made by Muhandiram D.A.L. Perera of the Archaeological Department in 1896-7.

Meaning and style

An important but unanswerable question is: how did the present figures relate to the entire composition of the painted band ex tending across the rock face? Their fragmentary nature and unu sual location have led to the Sigiriya paintings being interpreted in a number of ways, sometimes quite fancifully. Of the proposals that deserve scholarly consideration, the three most important are those of Bell (1897), and the two well-known Sri Lankan schol ars, Ananda CoomAraswamy, writing in 1908, and Senarat Paranavitana, half a century later.

Fig. 23 Apsaras

Bell’s idea that they portray the ladies of Kasyapa’s court in a. devotional procession to the shrine at Pidurangala is a purely im aginative construction and has no precedent in the artistic and social traditions of the region or the period. It seems quite likely, however, that the court ladies and their costumes and ornaments provided models for the Sigiriya artists. As such, the paintings would reflect the life and atmosphere, the ideals of beauty and the attitude to women, of the elite society of the time.

Paranavitana’s suggestion that they represent Lightning Prin cesses (yijjukumart) and Cloud Damsels (meghalata) is an inter pretation at once more literary and sociological. It forms part of his elaborate hypothesis which attempts to explain Sigiriya as an expression of the cult of divine royalty, the entire palace complex being a symbolic reconstruction of the abode of Kuvera, the God of Wealth.

While these identifications may seem to us today an over-inter pretation, too specific to accept in its totality, and deriving from Paranavitana’s attempt to see the Sigiriya palace and royal com plex primarily as an expression of divine kingship, they do draw our attention to important sociological dimensions in the under standing of ancient works of art. There is no doubt that the spatial organization and symbolism of the Sigiriya complex is profoundly determined by the cult of the king and the ideology of kingship. The great tapestry of paintings at Sigiriya, the palace on the sum mit and the lion staircase are all part of a complex ‘sign-language’ expressing royal power and ritual status

Coomaraswamy’s identification of the Sigiriya women as apsaras is in keeping with well-established South Asian traditions and is not only the simplest but also the most logical and acceptable in terpretation. Recent studies have reinforced this idea showing that apsaras are often represented in art and literature as celestial be ings who carried flowers and scattered them over kings and he roes as a celebration of victory and heroism. We can say almost with certainty that the Sigiriya ladies are celestial nymphs, very similar in essence to their successors thirteen hundred years later in the ‘Daughters of Mara’ panel in the Dambulla murals. Iiis also likely that they had more than one meaning and function, as ex pressions of royal grandeur and status, and as artistic evocations of courtly life, with aesthetic and erotic dimensions.

45 Such an interpretation with its varying levels of ambiguity al lows us to accommodate both Bell’s and Paranavitana’s sugges tions at either end of a semiological spectrum. It also makes it possible to view the painted band at Sigiriya as a rare and early survival of a royal citrasala or picture gallery, well known in Sri Lankan and Indian literature and described in the chronicle ac counts of 12th century palaces and audience halls at Polonnaruva.

The style and authorship of the paintings have been as controver sial a question as that of their identity. Early writers, such as Bell and even Coomaraswamy, saw them as extensions of the Central Indian School of Ajanta, or several related traditions such as those of Bagh or of Sittanvasal in South India. Bell even suggested that ‘artists trained in the same school - possibly the same hands - executed both the Indian and the Ceylon frescoes’. These were views expressed at a time when very little was known of the ex tent and character of early Sri Lankan painting.

The American art historian Benjamin Rowland was among the first to observe carefully the actual painterly technique at Sigiriya and to note in what specific way it differed from Ajanta and other subcontinental traditions. ‘The Sigiriya paintings outside of their exciting and intrinsic beauty are perhaps most notable for the very freedom they show at a period when the arts were tending to be come more and more frozen in the mould of rigid canons of beauty... The apsaras have a rich, healthy flavour that, in contrast, almost makes the masterpieces of Indian art seem sallow and effete in over-refinement... Just as the drawing is more vigorous than that of the more sophisticated artists of India, so colours are bolder and more intense than the tonalities employed in the temples of the Deccan’ (Benjamin Rowland, The Wall-Paintings of India, Central Asia and Ceylon, Boston, 1938:84, 85).

These insights have been pursued and reinforced by contempo rary Sri Lankan scholars who rightly argue that while the Sri Lankan paintings belong to the same broad traditions of South Asian art as the various subcontinental schools of the time, the specific char acter and historical continuity of the Sri Lankan tradition give it its own distinctive place in the art of the region. Thus the Sigiriya paintings represent the earliest surviving examples of a Sri Lankan school of classical realism, already fully evolved when we first encounter it in the 5th century at Sigiriya

Boulder Garden paintings

The art of Sigiriya is not confined to the great rock itself. Of equal archaeological and even aesthetic interest, though less well pre served and visible, are a number of paintings found in the shelters

Fig. 24 Fragmentary paintings from Rock-shelter 7

at the foot of the rock in the area that formed the Boulder Gar dens in the time of Kasyapa. As we have seen, this was also the centre of both the ancient and the post-Kasyapa monasteries. Significant fragments of paint-ings can be seen in at least five of these shelters. Many oth ers also contain traces of plas ter and pigment, indicating an extensive complex of painted caves and pavilions in the whole of the Boulder Garden area.

The most ambitious compo sition can be found on a large area of plaster in Rock-shelter 7 where there are faint traces of several female figures carrying flowers and moving amidst clouds, very much like the apsaras on the main rock above. Even in ornamentation and general figural treatment these women are broadly similar to those in the famous paintings, except for the fact that at least three of them are not cut off at the waist by clouds but are full figure representations with legs bent in a conventional flying posture. Altogether there are about half a dozen identifiable forms here barely discernible in traces of body colour and linework.

Fig. 25 Details from ceiling paintings in Rock-shelter 9

The most extraordinary, and certainly the most dramatic mani festation of the painter’s art at Sigiriya, are the remains of ceil ing paintings in the rock-shelter popularly known as the ‘Cobra hood cave’ (Rock-shelter 9) on account of its equally dramatic rock formation. The shelter itself dates from the earliest historical phase of occupation at Sigiriya and bears a donatory inscription belonging to the last few centuries BC. The painting combines geometrical shapes and motifs with a free and complex rendering of characteristic volute or whorl motifs. It is nothing less than a masterpiece of expressionist painting, displaying considerable imaginative range and artistic virtuosity in a way not seen else where in the surviving paintings of the Sri Lankan tradition. The characteristic brushwork style and tonal qualities of the Sigiriya school are immediately noticeable here. There is little doubt that this awning is contemporary with the paintings on the main rock

Considered in their totality the paintings in the Boulder Gar dens at Sigiriya, though vestigial, provide important evidence of the continuation of the Sigiriya school over a fair period of time. Excavations have shown several post-5th century phases of oc cupation in the rock-shelters in this area, continuing until per haps as late as the 12th or 13th century. This situation is paral leled by the layers of plaster and painting which provide evi dence of several successive phases of painterly activity at Sigiriya.

Graffiti poems

The Sigiriya paintings have preoccupied visitors to the site over many centuries. After the abandonment of the palace in the 5th or 6th century and the establishment of a monastery in the Boulder and Water Gardens to the west of the rock, Sigiriya became a place of secular pilgrimage for visitors from all over the country who came to see the paintings, the palace and the Lion Staircase. Greatly inspired by the paintings, they composed poems, mostly addressed to the ladies depicted in them, and inscribed their verses on the highly polished surface of the Mirror Wall just below the painting gallery. Known as the ‘Sigiri graffiti’ and dating from about the 6th to the early 14th century, hun dreds of these cover the surface of the wall and some of the plastered sur faces in the rock-shelters below. Nearly 700 of these writings have been deciphered by Paranavitana (1930s to 1950s) and another 150 recently by Benille Priyanka (1990s). The poems ex press the thoughts and emotions of ancient visi tors to Sigiriya. They contain not only reveal ing comments on the paintings themselves and other remains at the site, but also provide insights into the culti vated sensibilities of the time and the contem porary appreciation of art and beauty.

Fig. 26 Rubbings of selected graffiti poems. For readings see S. Paranavitana The Sigiri Graffiti London, Oxford University Press, 1956: Nos. 133, 197, 208, 42, 75 (reading from top to bottom) Opposite page and page 50: see pages 70-71 below for sources of readings and translations of poems

Their bodies' radiance

like the moon

wanders in the cool wind...

The song of Lord Kital:

Sweet girl

standing on the mountain

your teeth are like jewels

lighting the lotus of your eyes

talk to me gently of your heart.

I am Lord Sangapala

I wrote this song:

We spoke

but they did not answer

those ladies of the mountain

they did not give us

the twitch of an eye-lid.

Are they frightened

the ladies with the golden skins

that they stand so silent?

This long-eyed girl

says nothing

but a flower flaunts in her hand.

Lovely this woman

excellent the painter!

And when I look

at hand and eye

I do believe she lives.

We being women

sing on behalf of this lady.

You fools!

You come td Sihagiri

and inscribe these verses

(yet) not one of you

brings wine and molasses

remembering we are women.

This divine maiden

is like the centre of a flower

cleansed by moonbeams...

Your hair floats not

on gentle breezes

their welcome blowing.

Why spend you the cold night thus grieving?

O beautiful doe-eyed lady

is it because Sigiriyas lord

left not for you his gift so dear

Ladies like you

make men pour out their hearts

and you have also thrilled the body

making its hair

stiffen with desire.

The long-eyed women

are parted from their lover,

are grieving for the king.

Their eyes are blue lotuses.

The song sung to the painting

The wind blew

Thousands

and hundreds of thousands of trees

which had put forth buds

fell down. The curlew uttered shrieks.

Torrents came forth

on the Malaya mountain.

The night was made to be

of the glow of tender copper-coloured leaves

by fireflies beyond count.

O long-eyed lady

the message offered by you

what sustenance does it afford?

Is it not our lord

...who has returned

to the palace

he once lived in?

...is he going away again

seeing that we remain behind?

Having seen them

(the ladies in the paintings)

one is not content...

see also, indeed, the mansion

in which they lived so happily.

Having heard...

that the mansion of the king

is said to please the mind

I looked at it

(but) even if I had

as many eyes as

there are stars

I would have

found no

pleasure in it

whatsoever!

(With) tears in my eyes

I saw

how a king had lived

as he pleased

on the mountain

inaccessible

lofty as the sky.

PALACE

The summit of the Sigiriya rock is a stepped plateau with a total extent of around 1.5 hectares. A brick-walled staircase originally gave access to the summit. It began within the lion gateway and probably had limestone stairs and a tiled roof. Footings for the brickwork, cut into the rock face above the lion, indicate the path of the upper sec tions of this stair case.

The palace was the centre of the royal city At its highest point it lies 180 me tres above the sur rounding plain and 360 metres above mean sea level. Not only the loftiest and innermost precinct of the Sigiriya complex, it is also the geo metrical centre of the modular grid on which the plan of Sigiriya was based. The central north south and east-west axes of the entire for tified complex inter sect near the mid point of the palace area. Located close to this centre is a massive rock-cut throne, which faces the inner city and ceremonial precinct to the east of the rock. The earliest surviving example of a royal palace in Sri Lanka, with its layout and basic ground plan clearly visible, it provides important comparative data for the study of Asian palace forms.

Fig. 28 Plan of palace

The palace complex divides into three distinct parts: the outer or lower palace, occupying the lower eastern part of the summit; the inner or upper palace, occupying the high western sector; and the palace gardens to the south. All three sectors converge on a large and beautiful rock-cut pool bordered on two sides by a stone- flagged pavement. This garden area is a combination of water, terrace and boulder gardens on a smaller scale than the great royal gardens below. A marble-paved walk runs like a spine down the centre of the complex. It separates the upper palace from the lower palace, forming an axial north-south corridor leading directly to the throne.

The summit has a number of water-retaining structures for rain water harvesting. Extensive tile and nail remains found in recent excavations are evidence that the buildings here were roofed. It is likely that rainwater run-off from these roofs provided the main water source on the summit. A wide rock-cut drain, running north south along the western edge of the rock and then vertically down the rock-face, carried surplus water from the summit to a large reservoir built against the south-western comer of the rock. As described on page 31 above, an aqueduct from this reservoir car ried water down to the ritual bathing tank and royal audience hall in the Boulder Gardens.

Footings cut into the rock-face indicate that a wall, similar in principle to the Mirror Wall, encircled the summit along its edges. The roofs, pavilions and upper storeys of the palace would have risen above this wall and been clearly visible from the gardens and the plain below.

The palace on the summit and the great lion presided over the surrounding countryside, a powerful expression of both actual and symbolic'royal authority and control over ‘a landscape of power’, radiating across the territory of the Sigiriya kingdom.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS

With more than a century of investigation at the site and intensive research over the last two decades, a great deal of archaeological information and material has been gathered at Sigiriya. Most of it relates, of course, to the major architectural remains and the layout of the city, palace and gardens. Smaller finds, such as pottery, beads, coins, sculpture, roof tiles, drain pipes and a variety of iron objects, give a vivid picture of the way the site was used and also help to determine the chronology of various levels and phases of activity.

As in most archaeological sites, a huge collection of potsherds constitutes the bulk of finds. This enables us to construct a de tailed occupational sequence in various sectors of Sigiriya. Among the most interesting finds are the cups, bowls, tray-bowls, serving dishes, lids, cooking and storage jars and flower pots from the period of royal occupation. Import ceramics, although relatively rare, and large numbers of Roman coins, are evidence of the Sigiriya kingdom’s trade and exchange contact with both East and West Asia.

Fig. 29 Some pottery forms (derived from excavated vessels and potsherds)

Recent excavations in the Sigiriya area have shown it to be a major centre of iron production. This may partly explain the ex tensive finds of iron nails, some more than 30 centimetres long, and iron bands and other artefacts used in architectural construc tion, as well as agricultural and military implements. Sigiriya’s largely timber architecture has long since disappeared. Its shadow, however, is found everywhere, not only in the post-holes and beam holes cut in the living rock or surviving as hollow spaces in brick masonry, but also in the iron elements referred to above and in elegant terracotta architectural detailing. Rooftiles have also been found in large quantities in most parts of the site. Two interesting chance finds many years ago, are the Sigiriya ear ornament, an extremely rare and unique example of Sri Lankan jewellery, and a blue-glazed jar of West Asian origin.

Souvenir sculptures: ‘Art about art’

It is clear that Sigiriya was for many centuries a centre of artistic and literary activity, as evidenced by the multiple layers of paint ing and the graffiti poems. Closely connected with the paintings and the poetry is a series of miniature terracotta figurines found in the de bris of collapsed structures in the Boulder Garden area on the western slopes at the base of the rock. These are among the most interesting ar chaeological finds from the Cultural Triangle excavations at Sigiriya.

Most of the figurines are female tor sos rendered in the familiar ‘classic realist’ style of the Middle Historical period (circa 6th to 13th century). The modelling shows a characteristic con cern with three-dimensional form and a sensitivity to both anatomical and decorative detail. From their archaeo logical context and style we may ten tatively date them to a period between the 7th and the 10th centuries. As far

Fig. 31 Souvenir terracotta sculptures

Fig. 32 Terracotta architectural ornamentation

as we know, terracotta figures of this specific type have only been found at Sigiriya but they are clearly related to a contemporary tradition of fine terracotta architectural ornamentation and sculp ture associated with Sigiriya and other sites in the region.

It is particularly interesting that these figures are representations or models of the famous apsaras of the Sigiriya paintings. The concept of the unity of sculpture and painting (i.e. the equivalence of the three-dimensional and the two-dimensional image) is a ba sic principle of South and Southeast Asian art. What is rare, per haps even unique, at this early period is to find works of art which are deliberate representations, or in this case actual models or mini ature reproductions, of other works of art — a process which can be described as ‘art about art’

The correspondences between the paintings and the sculptures and the diminutive size of the latter (usually between 10 and 20 cm) suggest that the figurines were portable objects and not part of any fixed architectural decoration. This further supports the notion that they are models or ‘souvenirs’. The production of models and souvenirs to be carried away by pilgrims visiting fa mous religious centres is of course an ancient practice well-known in the art and archaeology of Asia. Sigiriya, however, is an exam ple of a site rare in the archaeological record that seems to have been visited purely on account of its secular aesthetic and ‘ar chaeological’ attractions.

Just as the verses are mostly addressed to the ladies in the paint ings, the terracotta figurines seem to have been produced as sou venirs to be taken away by visitors who appreciated the paintings. This interpretation is preferable to one that would view the figures as decorative or iconic sculptures associated with the monastic structures among whose debris they were found.

The Sigiriya torsos, like the poems on the Mirror Wall, are un doubtedly an expression of ‘art about art’. They interest us not only as beautiful terracotta sculptures but also as unique historical documents supplementing the insights we gain from the poems into the society and sensibilities of the period.

The Sigiriya earring

An extraordinary find associated with Sigiriya is a unique ear or nament, now in the National Museum in Colombo (acquired 1906). Made of solid gold, it is 6.4 cm in length, excluding the pen dant stones. Its body is formed almost entirely of a series of intricate vo lutes, bursting out like flames or wave-crests, most of them terminating in a small hook and nodule. The volutes are symmetrically arranged on either side of a central cluster of semi-precious stones, of which only a large, milky white quartz remains in place. Three pendant stones complete the design. At the top, a smooth loop with scrolled ends has a sliding gate device which can be opened to attach the orna ment to the ear of a per son or a statue. The ear ring cannot be precisely dated but probably be longs to the period be tween the 8th and 10th centuries. Its ornamental detailing and sliding gate device are evidence of its Sri Lankan origin. Exactly the same volutes appear in the Sigiriya paintings. As a piece of jewellery, however, it has no known correspondences in Sri Lanka or anywhere else in Asia.

.Fig. 33 The Sigiriya ear ornament

Inscriptions

Sigiriya and the Sigiriya region have yielded a rich collection of inscriptions, dating from about mid-1 st millennium BC to the 18th and 19th centuries. They provide a complementary and sometimes alternative framework to what appears in the archaeological record, and throw light on changing values and the varying nature of what was considered important in social, economic and political life from epoch to epoch.

The first examples of writing on stone in this area are the sym bols or letters engraved on two capstones from the tombs in the megalithic cemetery at Ibbankatuva, dating from around 500 BC.

Fig. 34 Inscriptions: (a) Ibbankatuva, megalithic symbols: circa 500 BC; (b) Sigiriya, early Brahmi: 3rd-1st century BC; (c) Sigiriya, later Brahmi: lst-2nd century AC; (d) Unulugala, near Sigiriya, later Brahmi: 3rd-4th century; (e) Sigiriya, early cursive: 6th-7th century

The earliest and most prolific writings that have meaningful texts, rather than single symbols or letters, are the donatory in scriptions placed near the drip-ledges of rock-shelter monaster ies, recording the gifting of the rock-shelters to the Buddhist mo nastic order. Dating between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC, they use the universal Brahmi script found throughout South Asia. They provide a great deal of information regarding the social and po litical conditions and the names, titles, interests and values of the social elite of the time.

Less numerous than these drip-ledge records is a series of in scriptions, mostly from the 1st and 2nd centuries AC, indited on the rocks themselves rather than near the drip-ledges. They record donations to Buddhist monasteries by an office-holding elite in cluding kings, provincial rulers and army commanders. We see in them the increasing centralisation of political authority, the devel opment of irrigation and agriculture, and the growing wealth of the monasteries.

A third category is a handful of records from the 5th to the 7th century, a period which sees the transition from the angular letter forms of Brahmi to a much looser and progressively cursive script. These inscriptions, unlike those in the previous category, are not by kings or high officials. They contain the enigmatic term ‘vaharala’, whose interpretation is a subject of some controversy. Some authorities connect it with the manumission of slaves, oth ers with craft occupations, the ordination of monks, or donations to monasteries. The earliest graffiti on the Mirror Wall also be long to this phase.

From an epigraphical point of view the next group of records, the slab or pillar inscriptions of the 9th and 10th centuries, are important and extensive state documents, royal grants and legal edicts, promulgated by royal authority and erected by provincial officials. Although few in number, they give us a complex image of the legislative, executive and judicial machinery of the time. The period from the 8th to the 10th century is also the ‘Golden Age’ of the Sigiri graffiti. The largest number of well-preserved texts and the highest literary qualities are found in the writings on the Mirror Wall from this era.

There are scarcely any records of significance in the Sigriya re gion after the 10th century, with the exception of an elaborate royal inscription at Dambulla, from the last decade of the 12th century, and the Mirror Wall graffiti, which continue into the early 14th century.

The only other later period inscriptions that have been found are an incomplete royal edict of the 18th century and records of donations to the temple at Dambulla in the 19th and 20th centuries.

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE: THE SIGIRIYA HINTERLAND

The city, palace and gardens at Sigiriya, the Mapagala fortified site, the Sigiriya lake and canals and the immediately neighbouring mon asteries are all set in a rich natural and cultural landscape, impacted and fashioned by humans over centuries. Total archaeological land scape surv eys have given us a broad picture of the archaeology of an area of more than 1000 square kilometres around Sigiriya. This includes prehistoric sites, megalithic cemeteries, Buddhist monas teries, rural settlements, village tanks, and iron-production centres. The monasteries of Pidurangala and Kaludiya Pokuna and the World Heritage site of Dambulia are easily accessible to visitors, as is one of the megalithic tomb clusters at Ibbankatuva near Dambulla. The forest monastery and the natural mountain reserve at Ritigala, with its unique flora, is also open to visitors. Not too far away are the ancient capital cities of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruva, the archaeological sites at Manikdena and Madirigiriya, the great man-made lake at Kala Vava and the co lossal Buddha images at Avukana and Sasseruva.

Fig. 36 The ‘Greater Sigiriya’ area

Fig. 37 Sigiriya archaeological landscape

Pidurangala and Ramakale

As in most urban sites in Sri Lanka, and especially in royal cities, an integral part of the Sigiriya complex are the two outlying Buddhist monasteries of Pidurangala to the north and Ramakale to the south.

The monastery at Pidurangala, like Sigiriya, dates back to the earliest phase of the Early Historical Period when it was a rock shelter monastery with 14 shelters, four of which have donatory drip-ledge inscriptions of the 3rd to 1 st century BC (Kodituwakku and Karunaratne, pers. comm. 2002). The shelters also contain evidence of prehistoric occupation.

The complex as it is today is in three sections. At the base of the rock is the contemporary temple, whose image-house is a large ancient rock-shelter of the Early Historical Period, with a recumbent image and two standing images of considerable antiquity, but now restored and painted over. Associated with this rock temple are a number of buildings of the modem monastery, at least one, a monastic residence, dating-from the Kandyan Period in the 18th century or early 19th century.

On and around the great rock are rock-shelters which were used since prehistoric times. In the Early Historic Period they became monastic dwellings and were later converted into shrines. The largest and most accessible of these is the great ‘cave temple’ more than halfway up the rock, in a rock shelter 90 m long, divided into 13 compartments. The temple has remains belonging to several periods, including one of the earliest dated colossal recumbent images of the Buddha, dating back at least to the 5th century, but now restored. The image measures 12.5m.

The summit of the rock presents an extraordinary natural and cultural landscape. It is marked by a distinctive‘dry tropical’micro-environment with an unusual floral composition, and offers dramatic views of the north face of the Sigiriya rock and the Lion Staircase, against the distant backdrop of the central mountains. The remains of a votive stupa preside over the summit and the surrounding countryside.

On the plain below the Pidurunagala rock is a major monastic complex of the same pabbata vihara type as the monastery at the entrance to the Boulder Garden at Sigiriya - with a stupa, a Bodhi- tree temple, an image-house and a chapter house. At Pidurangala we also have a central mandapa or shrine. The earliest phase of this monastic complex dates from at least the 5th century. The stupa itself is thought to have been built by Moggallana I (circa 495-512) over the site of King Kasyapa’s cremation.

New inscriptional readings show that Pidurangala may be the ancient Dalha Vihara. There is enough archaeological evidence to accept the traditional ascription of the pabbata vihara itself and the great recumbent image to the time of Kasyapa and Moggallana in the 5th and 6th centuries. There are at least 12 inscriptions at Pidurangala dating from the 5th to 7th century period, while the style of the surviving brick-and-plaster architectural detailing in the rock-shelter housing the recumbent image indicates a 10th or 12th century date. Pidurangala therefore has a history which takes us from prehistoric times to the 18th and 19th centuries, and it still remains a living religious centre.

The monastic complex at Ramakale, on the other hand, which lies to the immediate south-west of Sigiriya, is largely unexcavated and no longer in worship, but is known from epigraphical evidence to be the ancient Mahanaga Pabbata Vihara. The name is found in two 10th century inscriptions, with similar contents. They contain the text of an ‘immunity grant’, promulgated by three officials, in the name of the king-in-council, giving the monastery and its occupams immunity from taxes and from the authority of royal and regional officials. They also give the right of sanctuary to those who ‘having committed the five great crimes’ take refuge in the monastery.

Today the complex consists of about 120 buried structures and an excavated and part-conserved stupa. Among the interesting finds from the monastery is a Meru stone, a symbolic representation of the cosmic mountain, depicting in registers what appear to be divine figures, devotees and scenes from domestic and rural life. The stupa is clearly visible from the approach road to Sigiriya when coming from the main highway at Inamaluva. Behind and around the stupa is the forested precinct, about a square kilometre in extent, containing a series of mounds and water pools, concealing the buildings and water features of the monastery.

Environment and bio-diversity

The Sigiriya area is also rich in environmental resources, intricately linking cultural and natural landscapes. The area immediately around Sigiriya is a nature reserve, highly forested, especially to the east of the rock.

The Greater Sigiriya area extends from Kandalama in the south east to Polonnaruva on the east and Ritigala and beyond to the north-west. Much of this region is an extensive tract of Dry Tropical forest, rich in flora and fauna, and one of the most intensively studied areas in the Sri Lankan Dry Zone from the point of view of bio-diversity research. Many mountain ranges and ridges, such as the Kandalama mountains (Eravvalagala-Dikkandahena- Tittavalgolla) and the Konduruvava and Sudukanda Ridges, forming the immediate backdrop to Sigiriya, are covered with primary forests.

Sigiriya has a new botanical garden, begun in the 1990s, and open to visitors on request. It contains a medicinal plant collection and rare, endangered and common plants and trees native to the region. On the Dambulla-Kandalama road lies the IFS-Popham Arboretum (belonging to the Institute of Fundamental Studies), which can also be visited with prior permission.

Sigiriya and nearby Habarana are well-known for their avifauna, and are the regular haunts of birdwatchers. The archaeological park at Polonnaruva is also a nature reserve, and has been a centre for primate studies and animal behaviour research for nearly three decades. The Mahavali ‘Elephant Corridor’ lies across the Sudukanda and Konduruvava mountain ranges immediately to the east of Sigiriya, and leads ultimately to the Minneriya-Giritale Sanctuary and the Wasgomuva National Park.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS