The evolution of a pictorial tradition

- ADMIN

- Nov 6, 2021

- 34 min read

Updated: Jul 5, 2023

The evolution of a pictorial tradition

Prehistoric Art 07

Early Buddhist Rock Monasteries 11

Classic and Late Classic Styles 13

The Gampola and Kotte periods 15

The Kandyan and Southern Schools 17

Transitional Styles of the Modem period 19

Context and Method 22

Sri Lanka has a long and rich tradition of rock and wall painting, extending possibly from prehistoric times, and at least from the 2nd or 3rd century BC, to the 20th century. The great majority of these paintings are found in Buddhist contexts — in monasteries and temples, many of them established hundreds of years ago. Historical chronicles record the use of pictorial representations in the relic chambers of Buddhist stupas, in monastic residences, and in architectural drawings, as early as the 2nd century BC. Fragmentary remains of early paintings are known from a number of ancient archaeological sites, while a great cycle of 18th-and 19th-century murals can be seen in many urban and rural temples, still forming part of a living religious tradition.

Secular paintings, on the other hand, are relatively rare though not entirely unknown. It is significant that the earliest securely dated paintings that have been preserved are the well-known female figures from the 5th-century palace complex at Sigiriya. We know little of the more ephemeral forms of secular art and painted decoration, although the application of polychrome decorative detail to personal and domestic articles and the use of painted textiles are familiar practices, well-documented from Late Historical times. Paintings and painted sculpture from ritual and ceremonial contexts associated with Buddhism or related cults — manuscript illustrations, painted cloth or paper hangings and scrolls, flags and banners, illustrative and decorative panels on ceremonial arches erected during the annual festival of Vesak? an array of wooden mask forms, paintings of astral deities associated with the Bali rituals2 — all reflect a many-faceted, traditional world of colour, which we perceive today only in an isolated and fragmented way.

The most ancient examples of an art form which transcends — because, at least in essence, it predates — the separation of religious and secular are the paintings and ‘engravings’ in a primitive style, found in ancient rock shelters. Some of these may well be of prehistoric origin, while others are clearly of more recent date and seem to have been produced by the forest-dwelling Vadda peoples, who like their hunter-gatherer ancestors of prehistoric times and other similar rock-art-producing

sewhere, used these shelters as seasonal dwellings. However rich these varied contexts, and however important they may be for historians, archaeologists and ethnographers, it is in the rock and wall paintings of the historical period that we find a substantive and interconnected body of artistic material, which allows us to examine and delineate a distinctively Sri Lankan tradition, with its own internal history of continuity and development.

If we set apart the ‘primitive’ rock-shelter paintings and graffiti associated with the prehistoric and the Vadda peoples, it is possible to subsume the main body of Sri Lankan rock and wall paintings in three distinct but related groups: the fragmentary paintings of the Early and Middle Historical periods, the murals of the Kandyan school and those of the Southern or maritime tradition. The first dates from around the 5th to the 13th century, while the others belong to the last phase of the Late Historical period in the 18th and 19th centuries. Figure 1 presents in diagrammatic form the chronology of these developments and their relationship to other aspects of the Sri Lankan pictorial tradition.

The schools of Sri Lankan mural painting that we encounter in historical times form the principal concern of this book. The pictures reproduced here have been selected to illustrate the thematic range, compositional methods and stylistic variety displayed in these wall paintings, as well as their historical evolution and functional context.

Prehistoric Art

For the archaeologist, concerned with the reconstruction of the patterns and processes of the past from its fragmentary material remains, one of the most elusive dimensions of human behaviour is ancient man’s use of colour for decoration, ritual or imaginative expression. Pigment, which is usually the material basis of colour, is not only the most fragile of artefacts, but is also doubly vulnerable, depending as it often does on equally fragile and perishable materials for its support. The existence, therefore, of ancient paintings anywhere and from any period is always a rare phenomenon, astonishing not only by virtue of their artistic character and the insight they provide into the imaginative and conceptual world of the past, but also for the sheer feat of survival. When that art relates to prehistoric times, the chances of survival are even more remote. Unlike with the art of historical communities, which are often linked with their modern successors, in prehistory we are faced with much broader time-scales and much greater discontinuities in social and cultural evolution

It is surprising, therefore, that we know as much as we do about the art of prehistoric man in many different parts of the world (as a result of archaeological investigations and discoveries, and through ethnological analogies with the art of communities which still preserve, or preserved until recent times, a prehistoric mode of existence).

Sri Lanka shares in this general experience, if only in a limited way. The early rock art and the associated lifestyle of the Vaddas make a tangible contribution to our understanding of artistic activity in prehistoric times, even though we know hardly more about the paintings themselves than that they are extremely rare and of uncertain date and origin. The study of this prehistoric art, while lagging behind prehistoric research in general, goes back to the turn of the century. The pioneer interest in the subject was shown by the archaeologist H.C.P. Bell3 and the ethnologists, Charles and Brenda Seligmann, who produced the classic study of the Vaddas.4 The Seligmanns were also amongst the first to investigate the connections between the basically stone-age way of life of the Vaddas, on the one hand, and prehistoric man in Sri Lanka, on the other, and to draw attention to the rock shelters occupied both by prehistoric man and the Vaddas and to the rock art found in those shelters. Subsequent work on the subject has been more or less limited to brief reports, notably the observations made by John Still on paintings in the Anuradhapura district5 and to P.E.P. Deraniyagala’s notes on a number of rock-shelter paintings and engravings at sites in the southeast and north-central regions.6

There are altogether about thirty-three cave and rock shelter sites at which paintings and graffiti have been recorded.7 They contain three basic types of rock art, as described by Deraniyagala: monochrome silhouettes, polychrome paintings and incised representations. The ‘artists’ have employed white or coloured clays, kaolin and ash, or have just bruised the surface of the rock in a primitive form of engraving. Line or ‘stick’ figures, thicker finger drawings and smears, portray stylized animal forms, hunting figures holding bows and arrows, men riding on animals, and geometrical or symbolic motifs. Some forms are highly imaginative or symbolized renderings in which the identification of subject matter is dependent on interpretation. Others are clearly influenced by more representational concepts, such as a man riding a horse or two human figures framed within a rectangle. The colours used are, as we might expect, earth colours — ash grey, light-brown or white, dull-red or, occasionally, a pale orange colour from ferruginous clay.

Fig. 2 Prehistoric’ or Vadda rock-art sites. (After Nandadeva 1985.)

Although similar in character and in the contexts in which they are found to the much more extensive and well-documented rock art of Central India,8 there is a considerable degree of uncertainty regarding the date and authorship of the Sri Lankan paintings. None of the examples has been recovered from excavated or stratigraphically related contexts nor dated by any objective method. Their ascription to the prehistoric period — or, more accurately, their classification as paintings and engravings of a ‘prehistoric type’— has been on a stylistic and locational basis. In many instances, it is not even clear whether these examples are nearly contemporary graffiti, produced by the Vaddas or other people frequenting these areas, or the productions of fore st-dwellers in historical rather than prehistoric times. This is not to say, of course, that their authenticity as an organic rock-shelter art is in doubt. On the contrary, their stylistic character and technique, and the clear correspondence they bear to rock art in India and elsewhere, confirm beyond question the fact that they represent the spirit if not the actual form of the earliest manifestation of pictorial art in Sri Lanka. We are nowhere closer to the art of the prehistoric period than in the handful of rock-shelter paintings and engravings that has so far been discovered and documented.

Other sources that recall the colours and images of this prehistoric world, such as brand marks on cattle9 or the brightly coloured animal and demonic masks associated with shamanistic rituals and ritualised theatre,10 or even the painted and incised designs on clay grain-storage bins (bihi citra)^ often bear unmistakable echoes of the style and imagery of the primitive rock-shelter paintings. In the much broader if still rather grey picture of Sri Lanka’s pre- and protohistoric past that is emerging today, as a result of the archaeological research of the last two decades, the early art of the rock shelters provides a bright if elusive image of the imaginative world of prehistoric Sri Lankan man.

Fig. 3 •Prehistoric’ or Vadda rock art. Kadurupokuna, near Mahalenama. (After Deraniyagala. ASCAR 1957.)

Fig. 4 ‘Prehistoric’ or Vadda rock art. Ganegama. (From a

photograph, ASCAR 1957.)

Fig. 5 ‘Prehistoric’ or Vadda rock art. Komarika-galge. (From a

photograph, SZ (2)1, 1951.)

Early Buddhist Rock Monasteries

If the rock-shelter paintings constitute, at least typologically, the art of the hunter-gatherers of the prehistoric epoch, and the mask and bihi paintings represent that of the early agriculturalists, the paintings of the historical period are a product of the great transformation that Sri Lankan society and culture underwent in the last few centuries BC: a leap from preliterate protohistory to the beginnings of literate civilization, with the institutional, technological and cultural developments that were part and parcel of that transformation. Thus the paintings of the historical period have little connection with the rock art of the previous epoch, except for the fact that the rock shelters used by the prehistoric hunting peoples were adapted by the early Buddhist monastic communities as monastic dwellings. These early rock-shelter residences, and their successors, became the most enduring monuments of Sri Lankan ‘architecture’ and thereby one of the main repositories of extant historical paintings.

As we may still observe at a number of sites, the Buddhist monks and builders developed a technique of deepening a rock shelter or cave by ‘peeling off’ the weathered surface and striated layers of the rock to form a deep cavity or declivity below a large natural boulder or projecting cliff face. The cavity thus formed was further protected by a deeply incised groove or drip-ledge, which marked the upper limits of the peeled surface. This drip-ledge quite effectively prevented rainwater flowing down the sides of the boulder or cliff, into the depression. The depression or cave, in turn, was enclosed and enlarged by the addition of frontal screen walls — originally made of mud and wattle or rubble, later of brick or stone masonry — and was surmounted by a lean-to roof to form a ‘cave-dwelling’ or later a ‘cave-shrine’. The rock-face was then plastered and the plastered surface, including the internal walls, was finally covered with paintings.

The dates of the earliest of these rock-shelter monasteries are firmly established by the existence of donatory inscriptions, usually located just below the drip ledge. Familiarly known as the ‘Brahmi’ inscriptions, on account of the Indian alphabet they use, they are written in the local proto-Sinhala language. Nearly three thousand such inscriptions, dating between the 3rd century BC and the 1st century AD, have been recorded.

The rock-shelter and walled-in-extension concept maintained an extraordinary history of continuity in the Sri Lankan tradition. Many of the sites established at the beginning of the Early Historical period were occupied through Middle Historical Times, Although they were generally Converted into in to shrines rather than dwellings; i.e. with a ritual rather than a residential function. Many of these were also restored or refurbished in the Later Historical period and especially during Kandyan times in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some of the most famous sites associated with the late-period murals, such as Dambulla or Mulkirigala, have a history covering two thousand years of occupation or repeated restorations.

The rock shrines at Mulkirigala were established as monastic dwellings in the period of the Brahmi inscriptions. They are known to have contained murals in the early 18th century, and were repainted in the late 18th and then again in the mid-19th century.12 Similarly, the rock temples at Dambulla13 belong to a group of more than seventy such shelters used by one of the largest monastic communities of the early period. They still bear the donatory inscriptions of the period BC, and contain fragments of painting belonging to the Middle Historical period and sculpture and epigraphical records of the 12th century. The four main shrines were completely restored in the 18th century and a fifth in the early years of the 20th.

Recent excavations at Sigiriya reveal a series of developments extending from the 2nd or 3rd century BC to the 12th or 13th century.14 Brahmi inscriptions, periodic extensions of drip-ledges and deepening of rock shelters, successive layers of plaster and painting and at least five or six reconstructions of the walled extensions and the internal partitions, are all represented in the archaeological record. Elsewhere, archaeological investigations have revealed repeated occupation of rock shelters in both prehistoric and historic times.15

Fig. 8 Early Buddhist rock-shelter residence. Cave 9 (‘Cobrahood Cave’), Sigiriya. c. 3rd-2nd century BC. A Brahmi donatory inscription beneath the drip-ledge establishes the date of the original shelter. Ceiling paintings from the 5th century AD indicate the continuing occupation of the cave in later times.

Classic and Late Classic Styles

The patterns of development seen in the evolution of the rock monasteries and shrines — such as the formation of an indigenous Sri Lankan tradition linked with, but distinct from, that of the Indian subcontinent, and the continuity and reinterpretation of that tradition through a long historical trajectory — are equally applicable to other fields of cultural activity such as painting and sculpture. The earliest paintings that accompanied the formation of a Sri Lankan Buddhist architecture are no longer extant. Literary and epigraphic records, however, show an active propagation of the painter s art during the remarkable cultural efflorescence of the Early Historical period. Stone relief sculptures from stelae of the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, associated with the early stupas, anticipate the art of Sigiriya and the paintings of the Middle Historical period, and give us some idea of the stylistic continuity that must have prevailed between the two epochs.

It is in the transitional period of the 5th century at Sigiriya that the Sri Lankan pictorial tradition actually comes into view. By this time — keeping well in step with the most advanced developments on the subcontinent — there has already evolved in Sri Lanka a fully articulated and mature school of painting displaying what we may call a classic style. Judging by the affinities this has with the sculptural representations of an earlier phase and with the related history of architecture, the genesis of this style must date to at least the early centuries of the present era. Characteristic of this classic style are compositions in which the human figure is dominant and in which both the male and female form is rendered in a highly refined, sensitive but idealized naturalism. Each figure is invested with an individual character, while idealized notions of the perfection of the human form dominate the individual ‘portrait’. Personal ornament and decorative motifs are important but always relegated to a subordinate and supportive role, whilst repetition, when it occurs, is usually mitigated by the individualized treatment of each subject or motif.

Due as much to a freak of nature as of history, the well-known paintings of celestial nymphs in a depression in the great central rock of the 5th-century palace-city of Sigiriya are not only the most outstanding but also the best-preserved and earliest datable examples of the classic style. What we see here are several ideal female figures, which are at the same time portraits depicting individuals of different ages, physical types and personalities.

After Sigiriya we can trace this style, and variations and developments of it, through a period of nearly eight hundred years by studying fragments and traces of paintings at nearly thirty archaeologial sites distributed throughout the country. The paucity of remains at most of these sites does not allow us to make anything more than broad generalizations about the ‘schools’ or ‘ateliers’ that seem to constitute the spectrum of the Sri Lankan tradition. Significant patterns of similarity and differentiation are noticeable, however, between the fairly well-defined characteristics of the school of Sigiriya — which seems to have continued here beyond the 5th century — and the ateliers represented, if only marginally, at other sites not so far removed in date from the 5th century, such as Kandalama16 (Pl.19) and Gonagolla17 (Pls.20, 21). Both these sites, like most others of this period, are rock-shelter residences or shrines. The limited nature of the examples that have survived does not allow us to speculate whether the stylistic variations we observe are a result of differences in painterly treatment, subject matter and mood or regional and chronological factors. Again, from a somewhat later period, the paintings at Pulligoda18 (Pls.23-25) and the elaborate composition at Hindagala19 (Pl.26) show stylistic developments which are not only different from each other but are also intermediate between Sigiriya and the later paintings of Polonnaruva.

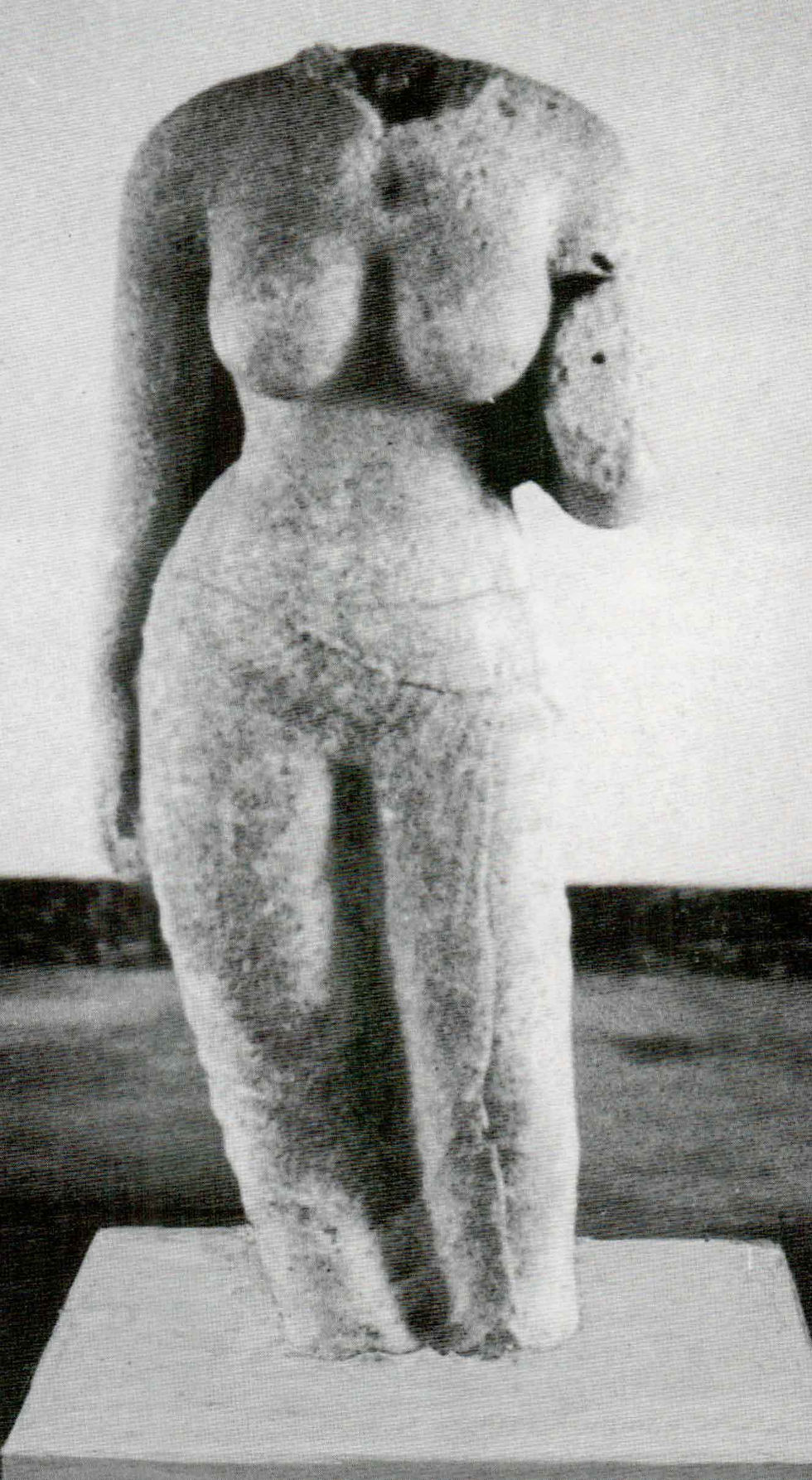

Fig. 9 Torso of female deity. Provenance unknown. 5th-7th century AD. Now in the Archaeological Museum. Anuradhapura. This dolomite sculpture has been assigned to the Middle Historical period but represents a treatment of the female form that goes back to at least the 2nd-4th century AD.

Fig. 10 Brahmas and devas in a celestial palace. Fragmentary painting. Vijjadhara Guha, Uttararama (Gal Vihara), Polonnaruva. Last quarter of the 12th century. (After Dhanapala 1957.)

The culmination of this development is the late classic style of Polonnaruva. The 12th-century Polonnaruva murals are in a high style of great elegance and richness of treatment. Descended from Pulligoda and Hindagala in their treatment of form and volume and their complexity of composition, they are executed in a much more controlled and deliberate manner than the paintings at Sigiriya. Badly faded or extremely fragmentary though most of them are, we can see that the direct and sturdier style of Sigiriya has now been replaced by a much softer and more dissolved sense of form. Also, unlike the pre-12th-century epoch, which is almost entirely restricted to rock paintings, vestigial remains and traces of murals are found in a number of brick-built shrines at Polonnaruva, most of them dating from the latter half of the 12th century. The most extensive of these remains are those at the Tivanka temple (Pls.33, 35-42,45); while some of the most eloquent expressions of the Polonnaruva school are from an excavated rock-shrine, the Gal Vihara (Pls.43,44).

The Tivanka murals are important in many respects. Although in a bad state of preservation, they are the only surviving examples of an at least partially complete cycle of paintings from the early period. Moreover, the Tivanka itself is the only painted temple or image-house of that epoch in which we may observe the organization and disposition of the murals and the utilization of wall space. What is most significant is that the arrangement of the wall paintings in large panel compositions or long successive bands or ‘registers’ and the choice of subject matter — such as stories from the life of the historical Buddha or the Jataka or ‘Birth' stories — are similar to what we find in the late-period murals of the 18th and 19th centuries. Moreover, the Tivanka paintings display several stylistic variations, including the grand manner of the late classic style of the 12th century and. at the opposite end of the spectrum, a sub-classic and a post-classic style, probably dating from the 13th century.

In considering the entire body of Sri Lankan painting, from the classic style of the 5th century to the post-classic styles of the 13th, we encounter an astonishing range of stylistic variation,as well as clear genealogical relationships. Thus we move from the hieratic geometry of Kandalama and the fresh exuberance of Sigiriya to the elegance and complexity of the Gal Vihara and the illustrational directness of the narrative registers of the Tivanka temple. At the same time, tenuous but clearly discernible links exist between these fragmentary images of a tradition which — within the parameters of the surviving examples alone — has a chronological range of nearly eight hundred years, and a previous history which is probably just as long. The Gampola and Kotte Periods

The 13th century marks a watershed in Sri Lankan history. The most visible manifestation of the changes that took place at this time was the shift in the main centres of political, economic and cultural activity from the dry zone plains of the north-central and eastern regions to the wet lowlands of the southwest and the central highlands. A significant development was the decentralization of political authority and, therefore, of patronage, resulting in the disappearance of the monumental complexes and the dissolution of the monumental style that characterized the civilization of the Early and Middle Historical periods. Conventionally viewed by historians as a period of decline, a loss of momentum affecting the entire civilization itself, recent interpretations suggest instead a transition to more complex and varied forms of polity, connected with underlying changes in social and economic organization. These early phases of the Late Historical period were times of commercial expansion, proliferation of urban and port centres, and considerable ethnic, religious and cultural diversity. They are marked in fact by major developments in literature and considerable intellectual vitality.

The inevitable consequences of such deep-rooted transitions are changes in religious and cultural activity as well as in the nature of artistic production.

The important, if relatively limited architectural and sculptural remains of this epoch testify to the continuity and development of the styles and motifs associated with the arts of the earlier period. The naturalism and individuality of treatment that marked the classic style in all its variations now give way to the formalization and decorative abstraction of the post-classic mode. At the same time, changes in technology and materials appear as important factors affecting, often adversely, the survival of cultural artefacts, especially in the field of architecture.

As far as the survival of wall paintings is concerned there is a hiatus in the archaeological record between the late 13th and the mid-18th centuries. Apart from the few rare examples of painted manuscript boards and some traces of old murals, all described below, we have no actual remains of paintings associated with the kingdoms of the post-Polonnaruva epoch, until the 18th century. Whatever developments may have taken place during this period in both the character and context of mural painting and other manifestations of the painter’s art, the basic reason for this gap lies in the fate of the architectural monuments themselves. The survival of the paintings is intrinsically linked with the survival of the monuments. Thus, ironically, the paintings of the Early and Middle Historical periods survived as a result of the abandonment of the early monumental complexes and rock temples in the 13th century. This made possible, even to a limited extent, their subsequent recovery in the modern period. The monuments of the post-13th-century epoch, in contrast, were not only different in character and often in materials, but were also subjected to very different processes of destruction and preservation. Those that were located in what was now the wealthiest and most advanced region, the southwest maritime zone, were almost entirely destroyed during the period of European colonial occupation. Thus there are scarcely any extant monuments or ruined complexes of the 13th-18th-century period in the maritime region, other than structures of colonial origin. Meanwhile, the monuments that were in the territory of the Kandyan kingdom — including temples such as those at Gadaladeniya and the Lankatilaka temple in Udunuvara (Pls.63-66 ),20 which were architectural conceptions as grand as any at Polonnaruva — were all periodically restored and refurbished especially during the Buddhist revival of the mid-18th century when a number of early temples and rock shrines were renewed and repainted. This well- established ancient practice of overpainting or repainting is documented at a number of early and later sites, including Sigiriya, Polonnaruva and Dambulla. The overpainting at Sigiriya and Polonnaruva is often within a narrow time range of less than a hundred years. At Dambulla we have an example of small fragments of early painting surviving on the rock-face outside the Kandy-period roof-line, while the internal surfaces of the entire complex have apparently been swept clean and repainted in the 18th century. A similar situation exists at Gadaladeniya. This 14th-century temple retains its original stone fabric and carvings and traces of early painting and decoration on its ceiling, but has a complement of paintings on its walls that is entirely of the 18th century. The subject of the early ceiling painting has been identified as the episode of the gifting of the white elephant from the Vessantara Jataka.2'

Literary descriptions and epigraphical records indicate considerable painterly activity during this period, not only, as Paranavitana observes, ‘on walls of buildings but also on wooden boards and cloth.’22 While Sri Lanka has no illustrated palm-leaf manuscripts in any way comparable with those of Nepal or eastern or western India — the only examples being manuscripts with 19th-century line drawings in a provincial style — at least three important, illustrated wooden manuscript covers exist, dating from the late 13th and 14th centuries. The earliest of these is the Cullavagga, a manuscript in the National Museum, Colombo, from the reign of Parakramabahu 11 (1230-

70) at Dambadeniya, with polychrome illustrations in a late Polonnaruva-period style (Fig. 12).23 The other two are the covers of the Saratthadipani manuscripts, in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris24 (which has floral designs), and the British Library in London, discussed below (Fig.l I).25 The only way in which we may recover at least some aspects of the pictorial style of this period is by referring to the manuscript-cover illustrations, the relief sculptures of the 14th century and the ivory carvings of Kotte and its successors in the 15th-18th- century period.-* The decorative ano narrative p.iicN of the sculptural friezes preserve the format of the narrative registers in the wall paintings at Polonnaruva. Similarly, the formalized treatment of the human figure derives from the later styles of t e Tivanka murals and anticipates the developments of the 18th and 19th centuries. There is no doubt, though we cannot easily document it, that the transition from the classic to the post-classic style took place during this epoch.27

The Kandyan and Southern Schools

Whatever the lost art of Gampola and Kotte might have been, correspondences in style and composition between the later, narrative paintings in the Tivanka temple and the murals of the 18th and 19th centuries, allow us not only to bridge a gap of five hundred years but also to conclude that there was a continuity of tradition, between the earlier and the later period. The stylistic connections between the two traditions are immediately apparent in their treatment of similar subjects. The organization and disposition of the Tivanka paintings and the choice of subject matter — Jataka stories in the antechambers, the life of the Buddha and representations of divine beings at the entrance to the sanctum or in the sanctum itself — are again similar to the general pattern followed in the later work. At the same time, echoes of the late classic style appear from time to time in Kandyan painting. In short, there can be little doubt that the paintings of the 18th and 19th centuries are the continuation of a tradition which has its genesis in at least the 12th or 13th century.

The late-period murals belong to two distinct but related schools: the Kandyan paintings of the central highlands and contiguous north-central plains, i.e. the area constituting the territory of the kingdom of Kandy in the 18th and early 19th centuries; and the Southern school of the lowland, southwest littoral. Both schools date back to at least the 18th century, with the Kandyan tradition being the earlier and, at least partially, ancestral to that of the maritime region. The best and earliest examples of Kandyan art date from the period of the revival of Buddhism and the renaissance of Buddhist art and literature that took place in the reign of Kirti Sri Rajasinha (1747-81).

Though no paintings clearly identifiable as belonging to a period before the mid-18th century can be found in the Kandyan tradition, it is entirely reasonable to assume that the renewal of the tradition during this time was not a new beginning but a continuation — at most after a brief interruption — of the prevailing style of the 17th and early 18th centuries. As we shall see, there is both material and literary evidence for the existence of mural paintings during the reigns of Kirti Sri Rajasinha’s predecessors. Moreover, in more senses than one, the kings of Kandy were the heirs to the traditions of Gampola and Kotte. Gampola is only a few miles away from Kandy and one of its kings built a palace in Kandy in the 14th century. Some of the earliest rulers of Kandy were feudatories of the kings of Kotte in the 16th century. There is no fundamental historical break between the earlier and later kingdoms of the Late Historical period. Temples constructed in the 14th century continued to be in use during Kandyan times.

The Southern temples, on the other hand, are mostly from the 19th century, the most mature expression of

Figs, lla-f (L to R) Dancers and musicians. Details from painted wooden covers of the Saratthadipani manuscript. 13th-14th century. British Library, Or. 6676.

Fig. 12 Dancing dwarfs. Details from painted wooden covers of the Cullavagga manuscript. 12th-13th century. National Museum, Colombo, 17/69.

this tradition being essentially a mid-19th-century phenomenon. The genesis of the Southern school, however, dates back to the early 19th or even late 18th century. This period saw the extension of the Buddhist revival to the southern territories, with the weakening of Dutch colonial authority in the maritime provinces and the arrival of the British. Temples such as Mulkirigala, which preserve some of the finest expressions of the Southern school, seem to have played a major role in the formation of this tradition. Located in a border area, at the southernmost extremity of both the maritime region and the Kandyan kingdom, Mulkirigala is associated with some of the earliest evidence for the existence of late-period murals from a time pre-dating the mid-18th-century revival. A European engraving of the 1730s shows the murals in one of the rock temples at this site (Fig.13).28 Subsequently, the temple is also mentioned in connection with the transmission or re-introduction of the mural tradition from Kandy to the southern region in the latter half of the 18th century.29

Fig. 13 Mulkirigala cave-temple. Detail from an engraving published in 1744 (Heydt 1952) and probably based on a sketch made by Arent Jansen between 1734 and 1737.

The two schools were closely related, but whether one was a branch or derivative of the other, or whether they were relatively independent developments, responding to similar needs, galvanized by the Buddhist revival, is a matter that cannot be easily decided. It is possible that the maritime tradition drew on vestigial survivals of the Kotte tradition as well as the prevailing art of Kandy.

What the two schools have in common and the extent to which they differ from each other can be seen at a glance, even from examples chosen at random, such as Pls.54, 55 and 72; and 143, 146 and 147. The chief characteristics of the Kandyan style are its heavy dependence on linework, not merely to define a figure but also to create visual interest and to generate pictorial activity in its own right; its use of a restricted range of colours, usually limited to yellow and red in the principal narrative registers; and the deployment of a relatively uncrowded picture space, using the red or yellow background and isolated figures to heighten narrative interest and visual drama. In some of its best examples, such as at Suriyagoda, the figures are almost expressions of pure line and form, each figure or group separated and suspended, so to speak, in monochromatic background space (Pl.55).

The Southern school, in general, while using similar techniques is far more elaborate, depending on a multiplicity of figures sometimes heavily crowded-in on each other, and a wealth of decorative detail. There is a much greater range and variety of colours and ornamentation, and the tonal modelling of faces and limbs creates a very different sense of liveliness and volume. The extremes of the spectrum, encompassing the stylistic range of the two schools, are represented by portraits from the Suriyagoda temple near Kandy and from two Southern temples (Pls.54, 145, 147). The paintings are separated by a hundred years or more — Suriyagoda dating from the latter half of the 18th century and the Southern murals from the late 19th century.

The contrasts between the pictures also point to the fact that while the Kandyan school remained very broadly within the parameters of its traditional 18th-century mode — this applies, for instance, to Kandyan murals painted as late as 1915, in the Alut Vihara at Dambulla — the Southern tradition was subjected to significant processes of development and change throughout the 19th century.

Transitional Styles of the Modern Period

The closing decades of the 19th century saw an acceleration in these processes of change and a critical turning point in the evolution of the Southern school, which ultimately brought about its demise. The collapse and disintegration of traditional mural paintings, from about the 1910s or 1920s onwards, and their replacement by contemporary renderings of traditional subject matter, belong as much — or more — to the history of modern painting in Sri Lanka, as to that of traditional art. A discussion of this lies beyond the scope of the present book. But our survey of historical painting would be incomplete without some reference to the transitional styles that emerged just before the turn of the century and which continued to influence post-traditional mural painting till the 1940s, and even to the present day.

Contemporary mural painting is generally considered to be a debasement of the artistic heritage of the late- period murals. To a great extent this is true. Much of the present work is a poor imitation or lifeless rendering of the compositional formulas and subject matter of the late- period murals, or is unskilfully derivative of the transitional styles of the early 20th century. It often exhibits poor artistic sensibility and bad craftsmanship, and is marred by the generalized use of industrial paints and varnishes. However, as a manifestation of contemporary ‘popular’ art, it operates within its own artistic and social context and has to be judged on its own terms. At its best, it displays the creative inconsistencies and awkward appeal of spontaneous, popular expression; at its worst, it reflects the impoverishment of both ‘popular’ and ‘formal’ culture in a transitional era. These paintings betray the meagreness of resources available today to a tradition which, in the not so distant past, was able to command a much greater wealth of imaginative and artistic experience.

As far as stylistic development itself is concerned, the origins of the present situation lie in the period between the 1890s and the 1930s. During these four or five decades, the art of the Kandyan school, or whatever strands of that tradition remained alive at the end of the 19th century, went into complete eclipse although a few families of painter-craftsmen still retained — as they do today — their skills and tools of trade. At the same time, the derivatives of the Southern style became fashionable and widespread throughout the country, often resulting in the overpainting of 18th- or 19th-century work, even in temples belonging to the Kandyan tradition.

There are several stages, still poorly documented and imperfectly understood, in the evolution of the

Fig. 14 Scenes from the Vessantara (above) and Dahamsonda (below) Jatakas. Gothabhaya Rajamahavihara, Botale. Early 1930s.

transitional style and of related styles and sub-styles. One of its earliest manifestations can be seen at the Karagampitiya temple at Dehiwela, to the south of Colombo. Here we have three sets of paintings, executed in the 1890s. The earliest of these, dated 1894, on the central wooden enclosure of the preaching hall, and a sequence of about the same date on the walls of the same building, show slight deviations from the normative style of the mid- to late 19th century, but remain within the broad conventions of that style. The Ummagga Jataka frieze in the ambulatory of the image-house, on the other hand, shows a definite break with tradition, a clear stylistic deviation from it (Fig. 94). Dating from 1897, these murals can be considered one of the earliest examples we have of paintings in a transitional style. At the end of the transitional period, several decades later, the Vessantara Jataka sequence at Botale represents a much more modern rendering of the same basic mode.

The essence of this stylistic mode lies in the use of geometrical perspective, an exaggerated and rather theatrical naturalism, and the mixture of stylistic and compositional elements derived, on the one hand, from traditional painting, and on the other, from European 19th-century illustration. Costumes, decorative motifs and ‘architectural scenery’ evoke a theatrical milieu, which we may identify specifically with the popular Nurti theatre of the late 19th century and its successor, the ‘Tower Hall’ traditions of the early 20th. The mixture of European and Indian conventions which marked both Nurti and the Tower Hall tradition is apparent in the paintings too. It is significant that there were some actual connections between the mural painters and the painters of theatrical scenery. Two of the most famous scene painters, the brothers George and Richard Henricus, were commissioned to paint murals in a temple at Dematagoda, a Colombo suburb, and their apprentice, M. Sarlis, went on to become one of the best-known illustrators of religious compositions. Sarlis’ scenes from the life of the Buddha

and from the Jataka stories were brought out in coloured lithographs, printed in Germany in the 1930s (Fig.15). The popularity of these prints and their wide distribution and the consequent adoption of this style in many temple paintings of that time, are often held to have brought about the demise of traditional painting. But we can now see that, while the Sarlis prints may have had a profound effect on the formation of popular taste and painterly practice, the transition from the stylistic conventions of the 19th century had begun much earlier. Moreover, a comparison of these Sri Lankan developments with similar trends in the mural and miniature painting traditions of South and Southeast Asia, shows that the appearance of eclectic, transitional styles, influenced by the academic realism of 19th-

Fig. 15 Prince Siddhartha displays his skill at archery. Lithographic print of a painting by M. Sarlis. 1930s.

Fig. 16 The Bringing of the Tooth-Relic to Sri Lanka (detail). From a mural by Solias Mendis. Kelaniya Rajamahavihara. Between 1932 and 1946.

century European art, was a general tendency in late 19th- and early 20th-century Asian art and not a phenomenon restricted to Sri Lanka.

One of the most interesting products of this transition, and one that goes beyond the boundaries of the transitional style itself, is the work of Solias Mendis (Fig. 16; Pls. 168,169)?° Starting as a traditional artist in the transitional style, Mendis executed new murals at Kelaniya, between 1932 and 1946. These are a remarkable achievement of contemporary painting, in the spirit and context of the

traditional temple murals, but in a style which is entirely a product of the 20th century. This style owes a great deal to the school of Ravi Varma and the painters of the ‘Bengali renaissance’, but displays a vigorous naturalism and strength of realization lacking in the Victorian sentimentality that often characterizes the Bengali work. The furthest development of this process is reached

when contemporary artists, working in an entirely different social and artistic context and trained in the modern European traditions of easel painting, turn their attention to temple murals. George Keyt’s work at the Gotami Vihara and Albert Dharmasiri’s paintings at Veheragodalla fall into this category (Figs.17,18). It is indeed the mark of a transitional society that while in the village of Nilagama descendants of the Dambulla painters of the 18th century still retain, if only vestigially, their traditional craft skills, artists nurtured in the conventions of the Ecole de Paris are inspired by the ancient mural traditions to decorate the walls of modern temples with contemporary interpretations of traditional subjects.

Fig. 17 The Buddha on his first alms-round, in the presence of King Bimbisara (detail). From a mural by George Keyt. Gotami Vihara, Borella, Colombo. 1939-40.

Fig. 18 The Birth of Prince Siddhartha (detail). From a mural by AlbertDharmasiri. Veheragodalla Vihara, Sedavatta.Kollonava. 1968/9.

Context and Method

The wall paintings in ancient shrines or modern temples remind us that there is a considerable degree of continuity, not only in the mural tradition itself but also in the contexts in which we find the murals, and in their organization, disposition and subject matter. We know from historical records and from archaeological finds that some of the earliest paintings were associated with stupas and monastic residences. Minute traces of plaster and pigment on architectural or sculptural remains at many ancient sites clearly indicate that buildings and sculpture were vividly and brightly painted and far more colourful, both internally and externally than is apparent from the bare brick and stone masonry that we encounter today. Nothing illustrates this better than the sections of painted architectural decoration still visible in the Tivanka temple at Polonnaruva (Pl.33). Surviving traditional practice and the monuments of the 18th and 19th centuries amply bear out this contention, except for the fact that in the later period, paintings and painted sculpture and decoration are usually restricted to image-houses and, more rarely, to preaching halls and are generally absent in stupas or monastic residences.

With the exception of the relic-chamber paintings from Mahiyangana and Mihintale and traces of decoration on the dagabas at Anuradhapura, the surviving examples of ancient painting are restricted to rockshelter residences or image-houses and the Tivanka temple at Polonnaruva. The image-house, therefore, occupies a special position in the study of murals in both the earlier and later periods.

A typical Sri Lankan Buddhist temple — or strictly speaking, temple-monastery — of the 19th or 20th century contains at least three major ritual monuments as well as a preaching hall (dharmasalava), one or more monastic residences (avasa) and sometimes, a chapterhouse (poyage) and a library. The ritual monuments are a stupa or dagaba containing relics, a bodhi tree surrounded by a terrace and one or more small image-chapels, and a central image-house. Though all three major monuments have more or less the same ritual status and equally complex architectural forms, the most intricate of these structures is the image-house, where the paintings are to be found.

The basic plan of the image-house, whether it is an ancient rock shelter, a temple of the 12th century, or a structure of more recent times, consists of an inner chamber, preceded by a vestibule, or surrounded by an ambulatory corridor, with a pillared veranda in front. Of course there are an infinite number of variations on this basic plan. The rock temples follow the natural configuration of the rock and of the original cave or rock shelter, but usually consist of a large internal chamber and a fronting vestibule and veranda (Figs.64,66). The Tivanka temple has a succession of antechambers leading to the inner shrine (Fig.42).

Many of the free-standing Kandyan temples of the 18th century, such as Suriyagoda and Madavala (Fig. 62),

are elevated on stone columns and have an open veranda forming an ambulatory around the inner chamber. In the Southern temples, at least three of the four major elements — inner chamber, vestibule, ambulatory and porch or veranda — are invariably present, as the accompanying plans show (Figs.84, 93).

Again, the disposition of the paintings and sculpture varies considerably from one temple to the other, but certain basic principles are adhered to everywhere. The inner chamber which forms the ritual centre of the building contains the principal icon, a seated, standing or recumbent Buddha, accompanied by other two- or three-dimensional representations of the Buddha, Bodhisattvas (‘Buddhas- to-be’), arhats (‘enlightened beings’), disciples and gods of the Buddhist pantheon. This chamber is rarely entered directly, but from an antechamber or ambulatory, while the doorway or doorways giving access to it are usually elaborately decorated and guarded by divine beings and attendants. The doorway is often surmounted by a makara torana or dragon arch.

Thus, with its statues, paintings and elaborate entrances, the inner chamber is at least implicitly the recreation of a cosmic or ‘other-worldly* realm or palatial residence, presided over by the Buddha, who is accompanied by an appropriate retinue, Even if, in practice, this iconographic complexity and symbolism is not operative in any precise or schematic manner, it provides a dramatic and devotional setting and a broad semiology of cosmic authority and power.

The walls of the outer chambers, on the other hand — i.e. the vestibule and the ambulatory — have a more didactic or instructive purpose, and usually constitute the largest area of wall space available for paintings. These walls are divided into long strips or registers, which contain narrative paintings whose subjects are drawn from Buddhist texts. The most popular items are those which are connected, in one way or another, with the life and antecedents of the Buddha. They include, therefore, the representations of the ‘Twenty-four Previous Buddhas’ (the suvisi vivarana, or ‘Twenty-four Annunciations’) with their distinguishing iconography; the principal events associated in the Theravada tradition with the life of the historical Buddha (the Buddha Carita)\ the Jataka stories, illustrating the life of the Buddha in his previous births as a Bodhisattva; and other stories taken from Buddhist literature and based on events or personalities associated with the Buddha during his lifetime.

The narrative registers, which extend horizontally along each wall, vary in Kandyan and Southern temples from about 40 to 75 centimetres in width. Narrower decorative strips with lotus medallions or flower garlands are often found at the top and the bottom, while in many instances the lowermost register is also divided vertically into panels depicting the various hells and underworlds of Buddhist cosmology. The wooden ceilings and, wherever they exist, the masonry vaults or arches, are decorated with floral and vegetal motifs, often resembling painted textile and cloth awnings. Some ceilings contain central panels or large, circular medallions depicting the planets, the zodiac, the guardian gods of the four or the eight directions and other cosmic or astral realms.

There is an attempt, therefore, to cover the entire internal wall surfaces and ceilings with colours and images which evoke, in both a two- and three-dimensional form, the world of the Buddha and of his disciples and followers; a world which is both historical and eternal; terrestrial and yet cosmic, of earthly inhabitants and of supernatural beings. It was clearly the intention of the designers of these temples to use sculpture and painting to create an exclusive, internal environment that was totally different from the world outside, to immerse the worshipper in a world of religious ideas, information and sentiment. The contrast between the external environment of white painted buildings and neatly swept sand courtyards, on the one hand, and the brightly painted interiors illuminated by windows in the ambulatories and with oil lamps in the inner shrines, on the other, helped to heighten, in a very dramatic manner, the sense of entering a special realm of existence. Using relatively modest architectural and sculptural resources and making extensive use of murals, the temples of the 18th and 19th centuries display a complex organisation of internal space. The spatial divisions of the temple, symbolically recreate a kind of cosmic geography, representing, in a highly complex way, the whole universe and both past and present time.

The wall paintings constitute one of the most important aspects of this complexity. In fact, we might say that the critical role in the transformation of the architectural interior into an ‘other-worldly’ environment is performed by the paintings and the painted sculpture which change a relatively familiar and dominantly anthropomorphic world into a supernatural or historical landscape, peopled by superior and ancient beings.

There is a noticeable sequence and hierarchy in the disposition of the various subjects represented in the paintings, based on alternating horizontal and vertical concepts of space and ritual importance. As each temple differs in significant details from the other and as no single temple displays the entire range of subjects, we can only present this hierarchy as a general scheme or normative pattern, in this way :

HORIZONTAL SEQUENCE

Inner Chamber

Central and subsidiary Buddha images

Bodhisattvas, arhats, disciples; gods (sequence interchangeable) Context and Method

Inner or Middle Chamber

The 24 previous Buddhas (suvisi vivarana)

Major events in the life of the Buddha (Buddha Carita) The 8 or 16 great places of pilgrimage (atamasthana or solosmasthana)

Middle or Outer Chamber Jataka stories

Major events in the life of the Buddha

Other events or personalities associated with the life of the Buddha

The locations associated with the Buddha's 45 annual rainy season retreats

Hells and underworlds

VERTICAL SEQUENCE

Upper Registers (or entire wall space of Inner Chamber) Bodhisattvas, arhats, disciples, gods (sequence interchangeable)

Ceilings

Cosmic or astral realms, planets, zodiac, guardian gods of the 4 or 8 directions, divine residences

Upper Registers (of Middle or Outer Chamber) The 24 previous Buddhas

The locations associated with the Buddha’s 45 annual rainy season retreats

The 8 or 16 great places of pilgrimage

Middle Registers (or entire wall space of Middle or Outer Chamber

Jataka stories

Major events in the life of the Buddha

Other events or personalities associated with the life of the Buddha

Lower Register

(Rarely, in inner chamber) the 8 or 16 great places of pilgrimage Hells and underworlds The murals (and painted sculpture) usually cover the entire wall space and use two basic forms of arrangement: either, large rectangular panels sometimes covering an entire wall, or — especially in rock temples — a large, well- defined area of ceiling space; or the familiar division into narrow horizontal strips or registers containing narrative paintings. A third form is a combination of these two, where the registers are vertically sub-divided into small regular panels, each representing a particular event, personality or place — as in the suvisi vivarana representations or in the depiction of the rainy season retreats, of the Eight or Sixteen Great Places of Pilgrimage and of hells and underworlds.

The compositional methods also vary in keeping with the different arrangements. The panels often use a centralized composition technique, where the principal subject occupies and dominates the centre of the panel — or, where the panel is one of a pair placed on either side of a central sculpture, the composition within the panel is directed towards the central image.

The narrative registers, in contrast, most commonly use the method of continuous narration, where the entire length of one or more registers is used to illustrate a story. Each part or incident in the story is depicted in sequence, one scene following the other without interruption. The ‘pictorial drama' in each register takes place against a continuous backdrop, usually a monochromatic red or black background, which unifies the narrative action and maintains its continuity both in space and time.

At the same time, the different parts of the narrative do not flow into or overlap each other, as they do in some pictorial traditions, but exist contiguously and on the same picture plane. Although there are vertical demarcations within each story, a change of action or of architectural or natural setting provides an indentifiable separation between ‘scenes’ and ‘episodes’. A smooth transition from episode to episode is ensured not only by the continuous background but also by the fact that the central character or characters in the story appear repeatedly in the same strip and sometimes twice or thrice in the same scene.

We see this, for instance, in a sequence from the Kataluva temple depicting the story of Patacara, a tale of human tragedy and pious devotion based on an incident associated with the life of the Buddha (Figs.87,89). Patacara is a tragic figure, who is driven out of her mind by the loss, in quick succession, of her husband, her children and her parents. Oblivious to the world, she wanders around naked. The Buddha alone, in his supreme compassion, understands her plight; and she finds solace and relief — in his preaching.

Figure 89 shows her appearing four times within a single scene; she arrives from the right; passes a palm tree —which, in a kind of cross-action, is being climbed by a man picking nuts — ; she approaches a crowd which has gathered to hear the Buddha preach, and then she sits down to listen to him. All this action takes place, so to speak, in a flash.

The technique is essentially theatrical or cinematic — or, in fact, closest to the method of the modern comic strip. Although the figures do not speak, except by action and gesture, a written commentary on the story — briefly identifying the principal incident in a given section of a register — is often provided on the narrow white bands which separate one horizontal register from another.

There is considerable variation in the way in which the episodic sequence of each story is chosen and presented. Much depends on the amount of space and the wall divisions available to the artist, as well as on his compositional preferences and the varying degrees of importance attached to the stories in the planning of the pictorial layout of each temple. The complexity of this layout and its infinite variations from temple to temple can only be appreciated in a schematic and comparative analysis, as we shall see later. In some examples each of the major episodes of the story is presented, while in others only a few, arbitrarily chosen episodes are shown. Sometimes a story is compressed into a small area by using a few familiar episodes, or even by the representation of a single event or scene; at other times the painter may use a great deal of space for one episode, while allocating much less to others. In general, however, the extended strip narrative, involving a regular pattern or rhythm of episodic sequence, is the norm.

The direction in which the story moves also depends entirely on location and spatial constraints, but the convention of a zigzag pattern, moving usually from upper to lower registers, is generally adhered to. Thus, the narrative action moves horizontally along a register from left to right or right to left and then, at the end of that register, continues in the register below, moving in the opposite direction. The artist, therefore, makes effective use of the fourth dimension, time. The observer moves up and down the room following the zigzag of the story as it unfolds from episode to episode and register to register.

Despite the familiarity of the stories and their remarkable

Fig. 19 Frieze of painted lions. Eastern vahalkada, Kantaka Cetiya, Mihintale. 12th century (?). (Drawing by Dayananda Binaragama,1985.)

Comments