Dwelling and Household: Activity Areas, Tools and Auxiliary Devices

- ADMIN

- Aug 27, 2021

- 55 min read

EVA MYRDAL-RUNEBJER, DAMAYANTHI GUNAWARDENA, SUDARSHANI FERNANDO*

* Damayanthi Gunawardena was responsible for the study of rural architecture and village layout. Owing to her sudden death in the field season of 1991, this work remains unfinished. We wish however to publish the material from the initial study, hoping it can be of use for more in-depth studies in the future. Help from Sudarshani Fernando and Manjula R. Sirisena of the SARCP team enabled the Talkote and Nagalavava house plans and the Nagalavava interviews to be completed. The PGIAR cartographic unit, together with Priyantha Karunaratne of the PGIAR undertook completion of the village plan of Nagalavava. Sarath Padmakumara and Sugath Jayasinghe, surveyors attached to the Sigiriya Project of the Cultural Triangle mapped Talkote village in 1989.

A few studies of Sri Lanka’s rural houses and household equipment have been published, but not specifically from our study area.1

In order to gain a better understanding of what activities could be related to a rural household in the area, and how they and their dwellings could be identified in space and from their associated raw material, tools and refuse, we initiated a study of village layout, house plans and activity areas in the house and courtyard.

Plans were made of three houses in Talkote village, and of all five houses in Nagalavava gammandiya. The overall plan of the villages was also mapped.

Though the sample is small, it is however possible to see significant differences in the house plans. It is possible to see a connection between relative material wealth and the house plan in the specialized functions of rooms, and building ma terial used.

House building labour traditionally was locally based, and did not involve paid labour. The raw material for the construc tion was locally available. It should be further studied to what extent the size of the household and its capability of raising additional labour from the neighbouring (most often related) community influenced the size of the house.

The latter aspect might also be related to the space that was allotted to each household for the construction. This could have a connection to the area of paddy land owned by the household.2

It was not possible to relate the difference in house size to caste affiliation in this small modern sample. Nagalavava is a low caste (Nakatikula) village, whereas Talkote is a Govigama village. In our example it seems that relative wealth is what determines the size and degree of differentiation of the dwell ing.3

No clear picture could be obtained regarding the tradition of men and women having different sleeping quarters. From descriptions of how the rooms were used, it seems that this custom was not practised in eight of the eleven households.

At present Nagalavava gammandiya contains seven hou seholds, all related by birth or marriage and all belonging to either of two kinship groups (Millagahagedara or Komgah- agedera).

Talkote, as discussed in the presentation of the study area, is mainly a paddy cultivating village; whereas Nagalavava is mainly chena cultivating.

PLAN OF THE VILLAGES Talkote

The present layout of Talkote village shows individual hou ses with surrounding home gardens dispersed mainly on the two sides of a gravel road (see fig. 18:2). The main tanks and paddy fields of the village are accessible through this road, which connects to the main road from Sigiriya to Kimbissa and Inamaluva and further, to Dambulla and Habarana.

The graveyard is situated 120m to the north of the centre of the village.

The former gammandiya area now is mainly a wasteland. It is situated between the two main tanks of the village. In this sense it wasn’t built in what is thought to be the traditional position: beside a tank bund. An abandoned settlement site named Pahala Talkote however was pointed out by the vil lagers as the former site of the village. It is situated west of the bund of the Pahala Talkotevava, which is the largest tank in the village. If this is the initial location, the former gamman diya (as the present position of the village) might signify a situation when additional tanks were incorporated in the vil lage economy. Today six tanks belong to the village, though two of them are abandoned and a third very seldom used. The breaking up of the cluster village started ca 50 years ago. We found the location of various functional features, such as storage facilities and kitchens, to vary among the houses. As the functional pattern of the common courtyard was dis rupted in Talkote when the houses were moved from the gammandiya, and hence also the orientation of the house, the traditional pattern might have been more uniform. No such pattern was seen though in the present day Nagalavava gam mandiya. The various functional requirements - that is, private space, public space, storage and food preparation space - sho uld have been the same however, previously too.

Disposal of refuse is an interesting subject from an ar chaeological point of view. In Talkote only a general view of garbage handling was obtained. Refuse here is most often swept into a heap in some corner of the individual courtyard. Dogs, cats and hens (and wild boar) will eat what suits them. Now and then the heap is burnt and the ash left to blow away

Figure 18:3 Plan of Nagalavava village.

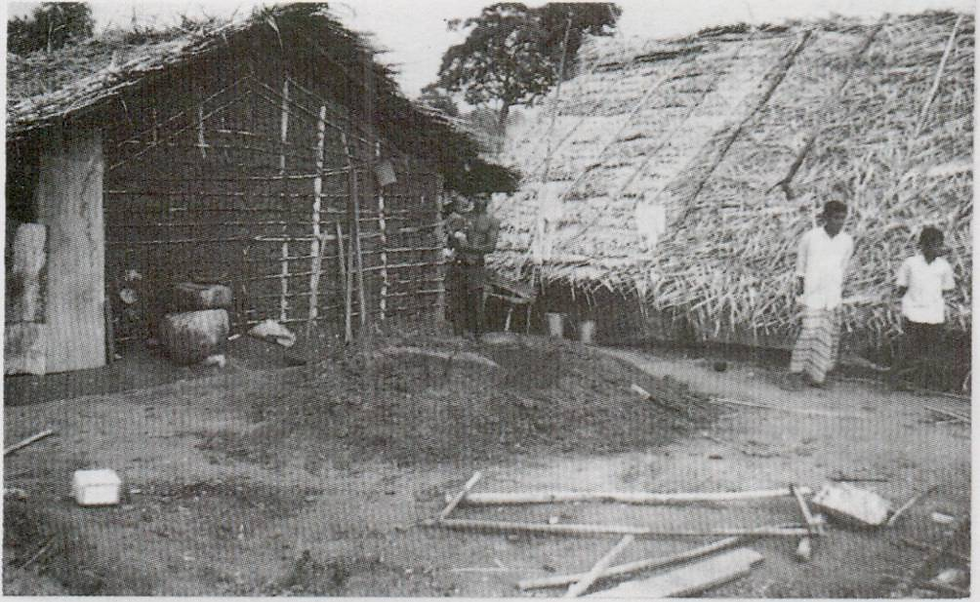

Nagalavava

Present day Nagalavava is divided into two. A severe flood ing in 1977 caused most of the villagers to move to the northern end of the tank (Nagalavava). The cluster village, containing five houses, some of them partly newly built, remains at the southern end of the tank. It is this part of the village that was mapped. The houses are constructed within an area ca 39x27m west-east (see fig. 18:3).

The tank bund constitutes the road between the two halves of the village. They are both connected by gravel roads to the Digampataha-Kimbissa road and hence further to Dambulla and Habarana. Footpaths also connect the village to Talkote and Pidurangala villages, to the east. Three tanks belong to the village today.

Until about 25 years ago, there were no toilets in the village (important for human coprolite analyses). The jungle and scrub land outside the tisbambe (cleared area around the dwellings, about 50m wide) were used for that purpose. Pit lavatories are used today by the two households with the largest and most functionally differentiated houses.

The graveyard is situated about 360m north-east of the village, in present day scrub jungle.

The cemetery is common to all members of Nagalavava village, there are no separate family burial grounds. According to the villagers, it is common to have one graveyard per village. Bordering the east of the present cemetery is the old abandoned one. Our informants said their ancestors were bu ried there. No investigation was made as to how ancient this practice of burial is.

The villagers fetch water from a common tube-well, but pne household (living in the next biggest and second most differentiated house) had dug a private well in their onion plot.

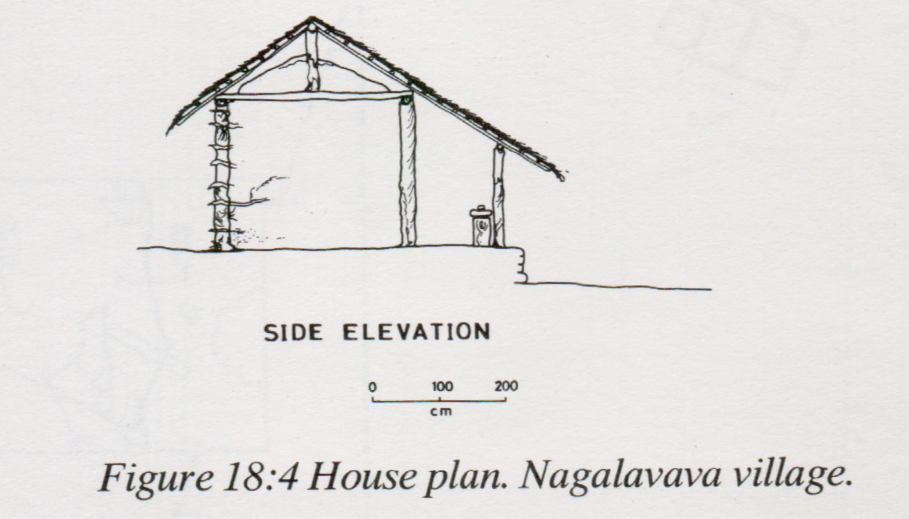

In Nagalavava, the question of how refuse was disposed was put to each household. The practice was found to vary among households. An old widow just threw the garbage alongside her house, without sweeping, burning or burying (see fig. 18:4). Another household dumped the refuse in a pit and buried it once the pit was filled, after about six to seven days. Behind one house a pit had been excavated to obtain material for an extension to the house (see fig. 18:7). This pit was being filled with garbage. When full, the household wo uld cover the pit with soil. The household with the most differentiated house said their refuse was dumped in a pit close to the tank bund (see fig. 18:6). Another household dumped the garbage at the rear of the house (that is, not onto the former common courtyard) and burned it when considered necessary (see fig. 18:8).

The Nagalavava example points to the fact that it might not be enough to identify refuse in the form of burned ma terial, for osteological and macro-fossil analyses in a rural settlement. Undifferentiated pits to which no clear function could be ascribed might be refuse pits, and soil samples could be taken to look for less destructible remains such as pollen and phytoliths.

PLAN OF THE HOUSES

Nagalavava

The main features of the dwelling houses in Nagalavava are squarish rooms and at front, a roofed platform - a verandah - and pitched roofs. Considering dwelling space the atupalla must also be mentioned. This is the space under the atuva (storage facility for dry grains, see below). The platform of the atuva is 0.6-lm above ground. The space beneath, ac cording to our informants, was used at times as a dwelling by poor villagers who had no means to build for themselves. Usually only one person at a time occupied this space, al though one family of six was mentioned as having lived under an atuva in the village. The last person to have lived in a Nagalavava atupalla was a widow. The owner’s permission was necessary to utilize the atupalla as dwelling space.

No constructions for storage of produce outside the houses are present today in the village. The remains of a cart stall however are seen north of the largest house. It once belonged to the house (see fig. 18:3). It is to be noted that it was sited outside (north of) the common courtyard.

With extensions to the houses, due to increased material possibilities and/or a changing family life cycle, the verandahs were seen to be built into the house. Today there are two open

verandahs left. One of them and all but one of the former

verandahs roughly face south. The other remaining open

verandah and one now enclosed are built opposite to these. One abandoned and partly demolished house is situated ca 40m north-west of the present village. Its entrance is oriented to the south-east, towards the other houses (see fig. 18:3). This indicates a former, common, central courtyard in the village.

Five out of seven households had a separate kitchen. The two without, consisted of a widow living alone in one case, and a newly married couple who had built a separate dwelling, an extension of the husband’s parental home.

A changed family situation had led to the largest and most differentiated house being abandoned a few months before the interviews took place. It was built in the colonial style, in 1955, bycarpenters, using cement for the flatform and tiles for the roof. But most houses are still built by the owners themselves, using material obtained locally. The present owner has moved to his parents in the main village and is planning to demolish the house.

The present village layout is in a state of change. This is not a recent phenomenon, as evident from the house con structed by carpenters in 1955. Yet Nagalavava still resembles the descriptions of traditional cluster villages, in that the houses don’t have separate courtyards.

Changing ground plan of houses

To give examples of the ‘life cycle’ of the houses, they will now be described one by one. Note that all square measure ments are approximations, as none of the houses, apart from the carpenter-constructed one, is built with perfect right angles. The inner square measurements given, include the open verandahs.

The widow’s house had contained three rooms and one kitchen, but her son had demolished three rooms (with her consent) to obtain building material for his own house. The widow, who had married a widower, said the kitchen had been built only after her marriage to him (see fig. 18:4).

The single bedroom cum kitchen of the widow measures 3.2x2.75m. The open verandah measures 4.8xl.8m. The door opening is 0.75m wide and situated in the middle of the wall. The hearth, built of three bricks, is in the south-eastern comer, opposite the entrance.

Previously the kurakkan gala (hand mill) was placed in the room, which has been her bedroom throughout, but after her husband’s death she doesn’t use it as often as before, and has put it in the verandah. There the miris gala (chilli-grinding stone) is also found. Rice is stored in an earthen pot kept in the room.

The house previously had a continuation to the east. The decaying platform is still faintly visible. Today the room and the open verandah have an inner square measurement of ca 17.5m2.

The house opposite has four rooms, a built-in verandah and a kitchen (see fig. 18:5). According to the owners, it was built around 1957. Initially the house consisted of two rooms in a row, with separate entrances from an open verandah facing south. The first addition to the house was the kitchen, built with a separate entrance from the courtyard, as an exten sion to the west. It measures 2.7x2.75m. The miris gala has been placed on a platform (former pila) inside the kitchen, which also has an entrance, in the form of a passage from the verandah. Later, the verandah was enclosed by building two rooms to the south. The main entrance to the house is now from the end of the former verandah in the east. It opens on to a sitting room without an enclosing wall, towards the former verandah. The other is an additional bedroom which has a doorway to the east, towards this room.

The first room to the right of the 0.85m wide entrance measures 3.15x3.65m. It is used as bedroom for the housewife and her two youngest unmarried daughters (26 and 21 years old respectively). The kurakkan gala is kept in one corner of this room. The original entrance, 0.65m wide, has been retained. The other room from the original construction is now used as a storeroom for sacks of paddy, kurakkan and the like. It measures 3.45x2.95m. Its entrance, measuring 0.65m is also left in its original position. Both rooms face the built-in veran dah which is now lm wide.

The room to the left of the main entrance is used as a sitting room, measuring 3.4x3.5m. It has thus taken over the ‘public space’ feature of the former verandah. This usage is consistent with the fact that it is not enclosed towards the former verandah. From this room a 0.65m wide doorway leads to the second additional room, to the west. It measures 3.2x3.3m. It is now used as the father’s bedroom.

The katta gana gala, for sharpening iron tools, is left outside the house. No other household uses this kind of shar pening device any more.

One interesting aspect of this changing house plan is that the principles of original usage have been kept. That is, private space, where the wife and husband don’t share a bedroom, and public space which has an open character. The extended build ing creates additional space for storage and food preparation. At present the inner square measurement is approximately 59m2.

East of it is the house built by carpenters (see fig. 18:6). Here the common plan of aligned rooms with separate entran ces to an open verandah is not seen. The present mainentrance, 0.85m wide, faces the abandoned cart stall. It leads into an L-shaped sitting room measuring 4m from the entrance and 4.4m and 3m across. This room was used as a bedroom by the present owner and his brothers when they were children, alternatively with the bedroom left of the main entrance. That bedroom’s sole 0.75m wide entrance is from the sitting room. The bedroom measures 2.65x2.45m.

Opposite the main entrance the sitting room has a 0.85m wide doorway towards an L-shaped, enclosed verandah. This was previously the bedroom of the owner’s sisters. It me asures 2.45m from the entrance and narrows to 1.7m west of the door. It measures 6.5m east-west. North of the sitting room there is another bedroom, used by the owner’s parents in the past. It measures 2.55x3.2m and its sole 0.6m wide entrance is from the enclosed verandah.

In front of the verandah two later additions were made. One was used as a storeroom for paddy and such produce. It measures 2.9x5m and has two doorways. One measures 0.8- 5m towards the former verandah and the other 0.9m, towards the presumed former common courtyard.

The other, later addition was a kitchen of wattle and daub, measuring 3.1x3.2m. It is now demolished. Its sole entrance, measuring 0.7m, was from the enclosed verandah. Where the cooking was done before this kitchen was built could not be found out in the interview.

What is common between this house plan and the others is that the two bedrooms don’t have a direct connection, but are entered from structures with a public space function. The inner square measure of this house is approximately 67m".

North-east of this house is a dwelling inhabited by two individual households (see fig. 18:7). On the first visit to the village in 1990, a family of five inhabited a house with one room, one kitchen and a verandah opening to the south. The room and kitchen had separate entrances from the verandah only. Rice and minor agricultural implements were stored in the only room.

Figure 18:7 House plan. Nagalavava village.

The family consisted of man and wife with their grown-up daughter and her daughter, and their grown-up son. In 1992 the son had married and an extension was made to (he house, towards the west. The son and his wife now live in one room, which is also used as a kitchen and for storage of rice and other agricultural produce. The verandah has also been ex tended, to the west, alongside the new room.

The original room, with a 0.65m wide entrance from the verandah, measures 3.2x3.6m. The kitchen, to the east, has an 0.55m wide opening to the verandah. It measures 3.15xl.6m. The hearth consists of three bricks placed in the south-western comer of the room, just to the right of the entrance. The verandah measures 1.7x4.25m. It is built roughly up to the entrance of the kitchen.

The newly built room has an opening 0.6m wide towards the newly built extension of the verandah. The room measures 3.1x2.6m. The hearth is built up by clay with place for two pots (two fires). It is situated in the south-eastern corner of the room, just to the left of the entrance. The extended verandah outside measures 1.75x3.25m. The households have neither kurakkan gala nor miris gala, nor vamgediya. Both hou seholds use the vamgediya of their neighbours, to the south (see fig. 18:9). North of the newly built room, at the rear of the house, there is now a pit. It was dug to obtain building material for the foundation and the walls. As mentioned earlier, it is now used as a garbage pit.

The original house has a ground plan measurement of ca 23.8m2. The dwelling of the young couple has a square mea sure of 13.75m2.

South of this house is yet another example of a dwelling that has been extended to house a newly married couple, close relatives of the original household (see fig. 18:8).

The original house was built by the widow’s uncle - her mother’s eldest brother. Thus it was built in the present inh abitant’s grandparents’ generation. It consisted of one room with an open verandah facing north. A kitchen has been added to the house at its eastern end.

The room measures 2.9x3.25m. It has a 0.55m wide ent rance to the former verandah. The enclosed verandah me asures 1.15x3.25m. The kitchen measures 2.9x1.75m. The verandah wasn’t extended to cover the kitchen; the kitchen is entered through a 0.5m wide doorway from a small enlarge ment of the verandah. The hearth is built up with clay, with provision for two pots (two fires). It is in the north-eastern corner of the room, just left of the entrance.

The miris gala is placed outside the kitchen, not to mess the floor while cleaning the grinding utensils, according to our housewife. Together with the vamgediya, kept on the partly enclosed verandah, it is shared with the other household and also those living in the house to the north.

The man living in the newly built house is the younger brother of the occupant of the original house and the woman the younger sister of the housewife. They have two small children.

The main, 0.7m wide entrance to their house is from the north. No verandah has been built here. A 0.25m wide passage at the opposite corner of the room leads to the now enclosed former verandah. The room measures 2.85x3.35m. The kitchen is built east of the bedroom and has a single

0.6m wide entrance from the room. The kitchen measures

2.85x2.9m. The hearth is built of clay, for two pots (two fires) in the north-western comer of the room, just left of the en trance. The kurakkan gala is in the kitchen.

The inner square measure of the original house is ca 1-

8.3m2. The extension measures 17.8m2.

Orientation of houses and extensions of buildings

In five cases a kitchen had been added to a house, but only in two cases as an extension in front of the original house, towards the presumed common courtyard. There was, lik ewise, no clear pattern as to the kitchen’s position in relation to the house. In three cases a kitchen had been added to the east of the house, in one case it was built as an extension to the west. Regarding the widow’s house, the now demolished kitchen had been situated to the east of the house. Room extensions had been made towards the common courtyard in three cases, and in one case towards the north, in line with the old house.

Various factors probably influence where additional rooms are built. The presence of neighbouring houses is, of course, an important factor. No house however, had been extended at the rear, that is the side opposite the courtyard. Future studies

should focus also on how land for dwelling houses is allotted in each case.

With the extension of buildings, entrances were situated in various positions, in relation to the courtyard. All five houses had at least one entrance towards the courtyard. The two largest houses, upon extension, had moved the main entrance away from the courtyard. The same was done by the ho useholders who let their siblings build an extension towards the courtyard.

One reflection that may be useful to future studies is that when the largest house has its main entrance on the opposite side from the courtyard, it indicates communication with the outer world (both as regards verbal communication and move ment and control of material things) more in the private inter est of this individual household than it is allowed to be the concern of the whole village.

Other features that were used by individual households, like the well, the two toilets and the abandoned cart stall, were all outside the courtyard.

Talkote

In Talkote, the three mapped houses each had a separate kitchen. The same variation was seen regarding material and technique of construction as in the Nagalavava houses; and in two cases the houses had been extended (see fig 18:10 and fig. 18:11). The verandah, for example, had been walled and made into a room, in two cases. The entire roof in the largest house and partly in another was now made of corrugated sheet metal. The floor in part of the largest house was also lined with cement, instead of clay and cow dung.

The most traditional of the three houses was built ca 50 years back (see fig. 18:10). It has two rooms and one kitchen, built in a row, with openings to the verandah only, facing south. The inner measurements of the rooms are 3x3. Im and 3x3m respectively. The kitchen measures 3x2.5m. The veran dah measures 9.25x1.25m. Half-walls are built around it. The inner square measure of the house, including the verandah, is ca 37.4m2.

The fireplace in the kitchen is made of five bricks, placed to support cooking vessels. It is situated in the left corner, opposite the door, to the north-west. Along the wall to the left, between the door and the fireplace, there is a wooden shelf for storing earthen pots and kitchen utensils. To the right of the door are a miris gala and two vamgediyas. Along the opposite wall, beside the fireplace there are four pots for storing water. Above the fireplace, is the dummassa (wooden frame on wh ich, for example, fish is dried). There is also a fireplace 7m west of the south-western corner of the house, used when large quantities of rice are cooked.

One of the rooms was used as a bedroom and the other for storage of food items and clothes. The household consisted of husband and wife with five children, aged between eleven and one. The verandah was used to entertain visitors.

The house in its largest part is built of local raw material, though part of the verandah is now covered by a corrugated sheet-metal roof, and part of the verandah platform has been aligned with bricks.

Another house consists of four rooms, with a smaller kit chen (see fig. 18:10). The verandah has been walled in on two sides. The fourth side, where the entrance is situated, has only a half-wall. The rooms are placed in a row, apart from the enclosed verandah which is now in a right angle to the rest of the house. The house has two entrances: one to the kitchen and the other to the former verandah, which is used as a visitors’ room and bedroom for males.

The kitchen measures 3.35x1.25m and is a later addition, with wooden instead of wattle and daub walls. There is a fireplace in the north-western corner and two pots for storing water, whereas the miris gala is placed in the courtyard, just outside the kitchen, where there is also a wooden shelf for pottery.

The two rooms following the kitchen measure 3.5x2.7m and 3.75xl.35m respectively. They are used for the storage of food and herbal medicines which are kept on wooden shelves, or hung from the ceiling. Pottery is also stored on a wooden shelf in the room next to the kitchen. In 1992 the largest of the rooms was also used as a bedroom.

The following room is a bedroom for women and children. The room measures 3.7x2.95m. In the floor we found a vam- gediya stone, the kind on which the vamgediya is placed for pounding. The stone was said to be used even at present. Sometimes items were ground or pounded directly on this stone. Its diameter was 0.3m. The visitors’ room and bedroom for males is the enclosed verandah, in right angles to this room. It measures 2.25x3.25m. The inner square measure of the house is ca 37m2.

In 1990 the household consisted of husband and wife and four children, ages 13 to 7.

The most complex house plan is the house with the cor rugated sheet metal roof and cement floors (see fig. 18:11). It was built in 1961. It consists of six rooms and one kitchen. This results from various additions to the original building. The house is rectangular, measuring 10x8m on the outside. In 1989 it had a small (2.5x2.5m) extension in the north-eastern corner, used as the kitchen by the householder’s father and mother. The house has two entrances, one to the main kitchen, the other to the sitting room. The kitchen extension has an entrance from the courtyard, but no direct connection to the house.

The main entrance leads to the sitting-room which me asures 3.6x4.5m. The sitting room is also used for storing agricultural produce (like onions). Right of the entrance is a room which was occupied by the householder’s parents. It measures 3.6x2.8m and its only entrance is from the sitting room. It was used as a bedroom and for keeping their belong ings. These two rooms have enclosed the former verandah.

After the sitting room comes the former verandah, measur ing 7.55x1.35m. It is now lined by cement and likewise used to entertain guests. Two bedrooms follow, measuring 3.2x3.65m and 3.1x3.6m respectively. Their entrances are from the former verandah, but they have no direct connection to each other. One of the bedrooms has an entrance to the kitchen. Food items are also stored in this room, hanging from the wall.

In the kitchen, measuring 1.85x3.75m there is a fireplace in the comer, left of the bedroom entrance. To the right is the entrance to the courtyard. Above the fireplace hangs a bag with dried fish. The grinding and pounding facilities are in the courtyard outside. The katta gana gala is also in the courtyard. Next to the kitchen is a room measuring 1.85x3.65m. It is used for storing pottery and other kitchen utensils. These ro oms are also extensions to the original house plan.

In 1989 the household consisted of husband and wife and five children from the ages of 19 to 7. The householder’s aged parents had a separate kitchen and bedroom and could thus, in a spatial sense, be considered a separate household. As regards food supply however, they were dependent on their son. They could not, therefore, be considered an independent unit of production. This points to one of the difficulties that could be encountered in an archaeological context, in trying to define the manpower of a household. In 1992 one of the elders had moved to the house of another of her children, and the se parate kitchen had been demolished. The householder and his family occupied an area of ca 63m2, whereas the aged parents occupied over ca 16.3m2 in 1989. In 1992 the remaining household occupied a house with a square measure of 73m2.

CONSTRUCTION OF HOUSES - THE

NAGALAVAVA AND TALKOTE EXAMPLE

Before building a house, the Nagalavava villagers say, it is customary to have the site examined by an astrologer. The planetary positions and the horoscope of the householder are consulted. Thereafter offerings are made to the guardian de ities of the earth, and the outline of the house is marked at an auspicious time. How a person obtained the right to build a house in the village and how the land was allotted, was not ascertained in this study.

The basic, structural elements of the house are the founda tion platform, walls and roof. The platform is built of clayey soil, to a height of about 0.2m. Ashley De Vos mentions that this kind of platform both hinders damp from entering the house and insulates the building from the heat accumulating in the surrounding ground (De Vos 1977: 46).

To build the roof, the four corner posts and taller gable post are erected first. They have a diameter of about 0.2m. They are sunk into the ground to a depth of about 0.6m. A mixture of sand and gravel is poured down into the post hole after erection of the post and pressed around it. Along the line of the wall, between the roof-support posts, thinner wooden posts are placed vertically (see fig. 18:12). They have a cir cumference of 0.1-0.15m, and are placed in post holes 0.4- 0.5m deep. Sticks are tied horizontally to the posts to support the wattle and daub walls. The walls do not join the roof.Construction of the walls commences only after the roof is thahatcched.

.

Figure 18:11 House plan. Talkote village.

The roofs are pitched. The gable and comer posts holding the roof have crossbeams connecting them. They rest on the roof-support posts in a slot cut into their upper end. No nails were used previously (see fig. 18:13). The rafters, placed in right angle to the crossbeams, were joined to them by kirival. In right angle to the rafters, wooden sticks are placed to fa cilitate the thatching of the roof with iluk straw, or cadjan (woven coconut palms). This is fastened to the roof by coir rope, or tied with the palm leaf itself. Cadjan is most often bought from itinerant merchants arriving before the start of the monsoon.

According to our informants, the cadjan roof will need replacement at least every second year. If it is attacked by termites it has to be replaced annually.

In Nagalavava we found the carpenter-built house to have a tiled roof. In Talkote, the largest and most differentiated house had its roof entirely covered by corrugated sheet-metal, whereas another house had part of its verandah covered by corrugated sheet-metal. This kind of roof cover necessitates less maintenance work, and that was the reason given for such material being preferred.

The walls are built with clayey soil. Fine clayey soil is pounded, the stones and gravel removed. Water is mixed with the soil and the mixture is trampled underfoot (see fig. 18:15). It is left for 24 hours, then made into balls and placed in the skeletal structure of the wall. Three days later a second pl astering is done. To fill in cracks resulting from the drying of the walls, a plaster of clay mixed with fine sand and water is daubed on the wall several times. This final coating is not applied by poorer villagers. No trowels or other implements are used to apply the clay to the wattle and daub walls.

To give a neat appearance, the outer wall can also be daubed finally with clayey soil mixed with cowdung, up to about 0.6 m from the outer platform (yatapild). The largest houses in both Talkote and Nagalavava were white-washed.

The walls of the dwelling were said to need repair once a year. White ants and the monsoon rains are the main cause. In Talkote, this was done before the New Year festival. We have also seen that the walls of wattle and daub houses left unin habited and unattended, fall into heaps of mud within a few years.

The floor is made by flattening out the clayey soil (on the platform). Thereafter the soil is mixed with cow dung and applied to the floor. The practice varied as to how often this coating had to be replaced. One housewife in Nagalavava reapplied it once a week. In Talkote, one housewife said she did it once a month. Even the largest house documented in Talkote had cowdung-coated floors in the latest built rooms.

Around the outer walls there is often a narrow platform like construction, the vatapila, about 0.3m high. This is built to prevent the supporting wall posts washing away. The clay that falls to the ground while plastering was used in Nagalavava village to construct this platform. In Talkote we found parts of outer platforms built of bricks, or sharp-angled stones.

In the process of constructing the wall, space is left for doors and windows. The doors are narrow. In Nagalavava, the average breadth varied between 0.65 and 0.9m. In Talkote the breadth varied between 0.7-0.85m. A wooden door-frame is placed in the opening, fitted firmly by creepers. The door has kudutnbi (tenons) at one comer, above and below. These are fitted into corresponding tauva (sockets) in the door frames. Halamba, teak and palu wood are used for doors. In Talkote we found a discarded yota (water-lifting device) used as a door, without tenons and sockets. In the average house, the doors are crudely finished. In Nagalavava, a simple flower motif about 0.1m wide is sometimes carved on the upper crossbeam of the door frame. This was not found in Talkote. Coomaraswamy noted of the beginning of the century that this beam was "...generally decorated." (Coomaraswamy 1956 (1- 908): 133).

In Nagalavava we were told that "in early times" door openings did not have attached doors. When the owner went out they would cover the entrance with a winnowing fan (kulla). No outsider would move the winnowing fan and enter the house. Later this was replaced by door leaves, but no latch (agula) was used. The closed door was tied with a rope fas tened to a post in the verandah (pilaf The purpose of closing the entrance was to prevent serpents and other wild animals entering the house from the jungle.

The windows, where they exist, are very small. The neces sary ventilation is provided by the gap between the roof and the walls.

RURAL HOUSES FROM AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL VIEWPOINT

Knox says of the Kandyan region in the late 17th century: "Their Houses are small, low, thatched Cottages, built with sticks, daubed with clay, the walls made very smooth...They employ no Carpenters, or house builders, unless some few noble-men, but each one buildeth his own dwelling. In build ing whereof there is not so much as a nail used; but instead of them everything which might be nailed, is tyed with rattan and other strings, which grow in the woods in abundance; whence the builder hath his Timber for cutting... The poorest sort have not above one room in their houses, few above two, unless they be great men." (Knox 1981:235).

The houses we documented, with two exceptions, are still built in this traditional way. We have found no rural settlement site remains that indicate a previous rural architecture using less destructible building material. We also see that the more prosperous villagers invest in larger and more differentiated buildings and modern building material.

Figure 18:12 Close-up of wall construction. The thin vertical sticks are bound to the wooden post with wickers. Talkote

village. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Figure 18:13 Joint of roof-carrying corner post, Talkote village. No nails are used in traditional rural house

construction in the study area today. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Figure 18:14 Preperation of clayey soil used to repair dilapidated wall in the background. Diyakapilla village.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Figure 18:15 Applying cowdung to the kitchen floor, for neat appearance and smooth surface. Nagalavava cluster village.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Only two families in Nagalavava had more than one room at their disposal, apart from the kitchen and verandah (see fig. 18:5 and fig. 18:6), and only five out of seven households had a separate kitchen. In Talkote we found separate kitchens in all three houses, and all three families had more than one room at their disposal.

In all cases where the building history of the house could be established, it seemed the kitchen constituted a later addi tion.

Whether this is a development of the latter half of the 20th century only, or if it was a practice previously too, to extend the house with separate kitchens or additional storerooms, we don’t know. According to Knox, it was not common in the 17th century Kandyan region. This should be further studied, together with the question: is there a difference between now and then, as to how land is allotted for building houses?

In Talkote, the inner square measure of the free-standing documented houses ranged from 37m2 (6.16m2/individual) to 73m2 (10.43m2/individual). The aged parents had occupied an area of 16.3m2 (8.15m2/individual), though of course they had access to the rest of the house also.

Unfortunately we don’t have information about the total number of inhabitants for all the houses in Nagalavava. The largest house in this village had a square measure of 67m2, but we don’t know how many lived there before the son, the present owner, took it over. The next largest house measured 59m2 (11.8m2/individual). The smallest free-standing house with one occupant measured 17.5m2. The young couple oc- cupied an area of 13.75m (6.87m /individual). Previously the whole family of five had occupied an area of 23.8m2 (4.76m2/individual). The young couple who had built an ex tension to their sibling’s house lived with their two children on 17.8m2 (4.45m2).

Of course, no conclusions can be drawn from this small sample. One trend however, was that the larger houses (73m - 59m“ in our sample) were also those that gave a larger area of individual-living in the house - the widow’s house being an exception. It should be examined whether the size of the house could be a useful indicator of household wealth. Probably the number of fireplaces is the best indicator of the number of households.

Most problematic still is finding the actual site of the house at all, in an area where surface pottery indicates a settlement. Unlike many regions of South America, where several archaeological rural sites have been studied with the focus on household wealth, Dry Zone Sri Lanka doesn’t have a rural architectural tradition of substantial stone platforms and foundations which make outlay and size easily visible.4 The earthen floor of compact soil and the aligning post holes would be the indicators of house size, and this is not visible (if at all) until the surface soil has been removed (see fig. 18:16 and group piece). This is true of course also of countries in temperate climates like Sweden, but soil properties, soil de position through monsoon rains, and lack of machinery, make

large scale openings of surfaces in Sri Lanka’s Dry Zone a time-consuming task.

Given the difficulty of identifying the individual house, it is likewise difficult to follow the other approach in studying household wealth - that based on household possessions.' However, relative difference of wealth among different settle ment sites might be possible to distinguish by following the latter line of research.

To identify and document houses in rural archaeology re mains a most important task. The solution is probably a greater (relative to the large elite structures excavated) investment of time and manpower in rural excavation.

investment of time and manpower in rural excavation.

Activity areas, tools and auxiliary devices

EVA MYRDAL-RUNEBJER

Eight families were questioned about material equipment and practices relating to household maintenance: three families of Talkote, one family from Diyakapilla, one from Pidurangala and one family from Kosgaha-ala. A family in Kayamvala was also questioned about mi oil processing, and a household in Nagalavava about the use of the kurakkan gala (hand mill) and storage of ground kurakkan.

In Nagalavava, a total inventory was begun of household equipment and locations. This interesting study is still not complete and will be reported separately by the researcher Sudarshani Fernando.

In the following we will try to give each item a place and date of origin, describe its specific physical form and function and compare it with the descriptions given by previous first hand sources. We must not think of the present ‘traditional’ set-up as something timeless and static, even if we find paral lels from the early modem era.

PROCESSING OF FOODSTUFF

The processing of foodstuff includes various labour proces ses such as pounding, husking, grinding, scraping, mincing, meat-cutting, boiling, steaming, baking, roasting, frying and preserving (through a variety of methods like smoking, drying, freezing, salting, preserving in honey, fermenting, churning, cheese-making etc.) depending on the cultural set ting under study. For archaeologists, food processing techniques are inter esting also because it is such labour that produces most of the orgsinic refuse from the settlement site - as well as our most chenshed datable settlement feature: the hearth! Ethno-botani- cal studies help us to understand in what way given species could be used in the household, and to know what to look for and where

Fireplace

The fireplaces seen in Talkote and Nagalavava were con structed either of bricks, usually three in a rough triangle, placed on their long ends, to stand the earthen vessel for cooking, or a clay foundation built to form a 3/4 circle, with the opening facing the room, the fire burns below, on the earthen floor (see fig. 18:17).

It is to be noted that the burning wood is usually a single branch, burning at one end and pushed further into the hearth as it burns. Such a technique leaves less charcoal and soot than if the fire is also used to warm the dwelling, when more wood has to be used.

In one household in Talkote, we found an additional fir eplace built in the same manner, 7m west of the south- we stern corner of the house. The housewife explained that she used this when cooking large amounts of rice in the big rice cooking vessel.

Husking and winnowing place

In Talkote, a palm roofed structure - the maduva - was built as an extension of the dry grain storehouse - the atuva. The roof construction was common with the atuva, the gable a height of 3.1m. Wattle and daub walls 1.3m high surrounded the earthern floor on the outer sides, except the entrance. The floor, measuring about 2.75x2.6m, was plastered with a mix ture of mud and cowdung. This structure was said to be a Traditonal additon to the "Atuwa" and used as shelter when husking wih the "vamgediya" and winnowing the husked seeds. in this household, the walls were also used for hanging fishing nets, and variety of other items were also hung or leant againsts the walls, in line with the floor level we siscoverd a very instersing feature: a flat stone with a diameter of 25 cm (see fig. 18.18}

No name could be given to it, but such stones were according to the housewife, meant to place the vamgediya on while pounding, so as not to damage the floor. We found a similar stone, its diameter 30cm, in another dwelling house, in the floor of the bedroom of the housewife and children (see ab ove). The housewife said the room was previously used as a maduva. It couldn’t be established if this meant the same floor was used for an extended room, measuring 3.7x2.95m, and once functioned primarily as a maduva. The room was at the opposite end from the kitchen, but the stone was still some times used. It had a slightly concave surface and the ho usewife told us that pounding was sometimes done directly on the stone, without the vamgediya.

In the former gammandiya of Ilukvava village (it was abandoned in 1942) we found a broken stone with a flat upper surface that had been used as a ‘vamgediya stone’ according to the villagers. It was not found in situ however, but thrown out into a former courtyard. The area is used for swidden cultiva tion nowadays, much favoured for the fertility of its soil (see fig. 18:19).

Robert Knox writes, based on his experiences in Sri Lanka between 1660 and 1679, that:

"They lay the Rice on the ground, and then beat it, one blow with one hand, and then tossing the Pestle into the other, to strike with that. And at the same time they keep stroke with their feet (as if they were dancing) to keep up the Corn to gether in one heap. This being done, they beat it again in a wooden mortar to whiten it...” (Knox 1981:240).

The stones used in these operations are much larger how ever than those referred to above7. So far, I’ve found no explicit reference to these smaller stones in the literature. If their function could be ascertained, we could take it as a food-processing indication when discovered in an archaeolo gical context.

Pounding facilities

In Talkote, both paddy and kurakkan and other dry grains are pounded in the vamgediya - a large mortar and pestle-like device - partly for the sake of husking the grain (see fig. 18:20).

Knox writes when listing household furniture:

"Also some Ebeny pestles about four foot long to beat rice out of husk, and a wooden Morter to beat it in afterwards to make it white,..." (Knox 1981:235).

The vamgediyas we saw were all made of wood, but John Davy writes that "the mortar is occasionally made of stone, but more generally of wood". He refers to it as a "rice-mortar or pestle, for pounding paddy, and depriving it of its husks." (Davy 1983 (1821:208).

Figure 18:17 The hearth is the archaeologist’s most cherished datable remains from household activities. The

present method in the study area however leaves a minimum of charcoal. The logs are slowly burned at their ends and

subsequently pushed into the hearth. Talkote village. Photo:

Eva Myrdal-Runebjer

We found it to be of importance also in the dry-grain economy, well integrated into the harvest and storage techni ques of ear-by-ear harvested dry grains. Davy might refer to another geographical setting, or might have overlooked this other use of the vamgediya, as we have no indications that the present practice derives from a time after 1819.

Robert Knox mentions that, as regards kurakkan, they "gr ind to meal or beat in a Mortar" and that "Tana" (Tanahal - Italian Millet) "is beaten in a mortar to unhusk it." (Knox 1981:112-113).

The vamgediya we documented was made by the present senior householder, who had worked also as a carpenter. We don’t know the age of this particular piece. The informants said such a device could be used for a very long time - "for 200 years", which if we don’t take it literally, at least indicates a possible usage of over two or three generations.

The mortar was made of alangu wood. It was 47cm high in all, with a base diameter of 28cm. The diameter of the inner orifice was 25cm, the walls were about 3cm thick and the carved depth of the mortar 15.5cm. The pestle was made of kaluvara wood. The pounding end was encircled by an iron ring. The pestle was, in all, 110cm long. The pounding end had a diameter of 5.5cm, whereas the upper part was 4cm in diameter. It weighed 2kg.

In another household we saw a similar device, worked by a seven-year-old girl who husked the paddy while the gra ndmother winnowed the husked grain. We have to consider children’s work within the household in discussing, for ex ample, household size and household wealth. This kind of partly needed, partly playful work carried out by children, with growing responsibility as they grow older, is evident the world over (even in the peripheral rural districts of a highly industrialized country like Sweden) and is, of course, difficult to measure in the sense of labour input and quality. What is important though, is that it represents reproductive work of life-supporting necessity, carried out under the watchful eye and instructions representant of a grown-up. As far as the individual household is concerned, the next generation’s sur vival depends on this, not at all glamorous, task of supervising and learning by doing - the only archaeological trace of which we see as chronologies.

Grinding facilities

Various devices have traditionally been used by the indi vidual household for grinding purposes, both rotary hand mills and grinding stones. In the villages we found grinding

stones for chilli and medicine, but not for grains (see below)

Figure 18:18 Rice is husked in the wooden mortar (vamgediya). Often it is husked and winnowed inside the shed (maduva) adjoining the dry grain storehouse (atuva).

Level with the floor of the maduva is a flat stone on which the vamgediya is placed. Example of an archaeologically visible

food-processing feature. Talkote village.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Figure 18:19 In the former courtyard (present-day chena field) of the abandoned gammandiya ofllukvava village a

broken "vamgediya-stone" was found. Broken and not left in situ it would have been difficult to identify in an

archaeological context. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Henry Parker, from his and civil servant Hugh Nevill’s observations in the field, in the latter half of the 19th century, mentions that the Vaddas (probably in the Vavuniya region) ground millet into flour on "a flat stone, or in a quern, by those who possess one...” (Parker 1984 (1909):52). As regards gr inding seed for flour, we might consider the difference in capacity and required labour investment between the grinding stone and the hand mill. We could also look into the labour invested in the making of the grinding stone as compared to the hand mill.

The dating of the first appearance of rotary hand mills in Sri Lanka is still obscure.

Figure 18:20 The grandchild pounding rice in the wooden mortar (vamgediya) placed in the coutryard, Talkote village.

To teach the younger generation practical tasks is an important part of reproductive work in any society.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

In Talkote village, we found no kurakkan quern in use. The lower part of a kurakkan quern was found in the site of the former gammandiya, one such part was used as a step below a fence; and a piece of stone found outside one of the houses formed an almost finished upper part of a kurakkan quern. The cutting had been started by the householder about 10 years ago, according to the housewife, but was now abandoned. Kurakkan is still grown by several of the visited households, which might indicates a shift in kurakkan preparing by the household, from grinding to pounding. None of the visited households sent their kurakkan out to be milled, as far as we could find out.

In Nagalavava gammandiya, several kurakkan querns we re found still in use (see fig. 18:21). The one we documented was typical, consisting of two nearly cylindrical pieces of stone placed one above the other. The lower stone, called the yati-gala, was sunk into the verandah of one of the traditional houses. It had a diameter of 25-27cm and was 11cm above the floor. Its upper surface was smooth and flat, though the sur face towards the edges was slightly worn. In the centre of the lower stone, a conically shaped peg was fastened in a hole. The peg was ca 3cm at base, thinning towards the top. It was made of gadumba wood. It was fitted; but with a lesser dia meter than the centric hole of the upper rotating part, called the matu-gala. The underside was smooth, but had the con cave form of a flat dish, probably through wear.

The stone was cut so that two knobs protruded over the lower part, in 200° angles to each other. In one of them was a hole, fitted with a wooden stick made of gadumba wood, used as the handle, to draw the quern. The upper stone was 27x40cm in diameter, and 11.5cm thick. The conically formed hole in the middle had an upper diameter of 6cm and a lower diameter of 3.5cm. The kurakkan seeds were poured in th rough that hole, the conical peg of the lower part helping to force the seeds to the sides. When pulled, the quern rotated round the wooden peg but also moved slightly sidewise, as the centric hole was wider than the peg.

This particular quern was made by a traditional Tamil stone-cutter from Digampataha village in 1935. It was transported to the village by bullock cart. His family carries on the stone-cutting tradition. Parallel to this traditional craft of cutting querns, ordinary male villagers in Nagalavava gam mandiya also dressed stones to be used as kurakkan querns. An example was the partly dressed lower section of a quern that was found outside one house. The wife of the house said an ordinary peasant of the village had worked the stone. He had learned the skill from the craftsmen. The quality of this layman work was not considered as good as that of the sp ecialists.

Robert Knox, from his 17th century horizon, says of kur akkan processing that "When they are minded to grind it, they have for their Mill two round stones, which they turn with

their hands with the help of a stick." (Knox 1981:112). Part of

the population however still used grinding stone and roller at

the end of the 19th century, as we noticed (above).

John Davy, based on his own observations between 1817 and 1819, describes a similar item which he named the "cor- rican-galle, or stone hand-mill". It was used to grind kurakkan and other small grains (Davy 1983 (1821):209).

Figure 18:21 A rotary hand-mill (kurakkan gala) in the verandah of a house in Nagalavava. The rotary hand-mill is a technical improvement of the grinding stone cum roller.

The latter was in use for grinding flour as late as the beginning of the century, in some places of the island.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Figure 18:22 Chili grinding stone and roller (miris-gala) outside a kitchen in Talkote village. Note also the pottery stored on wooden frame to the right - a common sight in

villages. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

The grinding of kurakkan might be linked to a more ge neral discussion of social development. Take, as a starting point, that the kurakkan quern probably represents a labour- saving device within the dry-grain economy (this could be investigated). It also represents a larger amount of invested labour in the making of the quern. This is an interesting aspect when comparing different communities and also individual households, using either the quern or the grinding stone and roller.

The relation of household wealth to household size has, of course, to be taken into consideration. The positive benefits of a labour-saving device such as the kurakkan quern are greater in a large household. What the large household makes pos sible perhaps, is to be able to feed household members not only when they are directly involved in food procurement activities, but investing labour in technological work such as cutting stone for making a kurakkan quern. It shortens the time women spend in grinding, giving them more time to take part in productive labour.

It may be at this very basic level that we should seek the answer to what made the emergence of a stratified society in a given area possible. It is also at this level that we find the circumstances in which new techniques or cultural patterns are and can be adopted by a community.

In our study area chilli and other ingredients for curry making are ground on the miris gala (chilli-stone). The miris gala we studied was a rectangular cut stone made from a piece of locally available rock (see fig. 18:22). The upper side was smooth by use. According to the owners, any stone can be used. This was 55cm long, 45cm wide and 14cm thick. It was placed outside the kitchen on a wood trunk 34cm high and stabilized by small pieces of wood. The roller was of stone, 18cm long with a diameter of 9cm. In other households the miris gala was placed inside the kitchen.

Coomaraswamy gives the name "curry stone (kudu miris gala)" and describes it as "a plain slab and roller" (Coomaras wamy 1956 (1908): 147). John Davy writes that "a couple of smooth stones are used, one small and the other large, for mixing together intimately and grinding finely all the different ingredients of their curry." (Davy 1983 (1821):210). Robert Knox describes it 140 years before Davy: "A flat stone upon which they grind their Pepper and Turmeric, &c. With another stone which they hold in their hands at the same time,..." (Knox 1981: 236).

For grinding various products used in traditional medicine, the behet ambarana gala (‘medicine grinder’) is used in Ta lkote (see fig. 18:23). Not every household makes traditional medicine, yet practising traditional medicine doesn’t neces sarily involve high specialization. The behet ambarana gala we measured was used in the household by the householder’s old father. He had also been practising a little carpentry for the neighbours, had previously acted as the vel vidane of one of the local tanks, in his capacity as one of the large landowners in the command area of that tank, doing paddy and chena cultivation and owning cattle, hens and previously, goats.

The stone had been cut from a locally available rock. This particular stone had been in use for 30 years. It was placed on the ground inside the karatta maduva (shelter in the courtyard where the bullock cart, the plough and various other larger tools and implements are kept). It was irregularly trough shaped, its convex underside stabilized by a small stone, when used. It was 44cm long, at its broadest upper side 28cm and its narrowest, 13cm. It was at most 7cm thick. The roller me asured 9x6x5cm and was described by the users as an ordi nary stone, picked for the purpose.

Figure 18:23 Medicine-grinding stone

(behet-ambarana-gala) under a shed in a home garden in Talkote village. Most people gather leaves and plants which are dried and used for medicinal tea. Several knowledgable people of the village also make herbal medicines, using such

grinding stones in the preparation. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

It differs markedly from the behet gal from Balangoda, used in the preparation of herb and mineral medicines and for the grinding of colours by painters, described by Coomaras- wamy. The illustrations show two behet gal which have a square-cut outline and a marked and even oval depression for grinding. Below the protruding, square-cut grinding section four cobra heads are carved, one in each corner. The top of the pestle is carved into a head. The form of the pestle indicates a vertical grip by hand, in contrast to the horizontal grip dem onstrated on the roller of the Talkote behet ambarana gala, indicating a pounding rather than a grinding movement (C- oomaraswamy 1956 (1908): 147, Pl. LII.,7).

We don’t know, however if such stones come from an ordinary rural household, or from secular or religious elite surroundings; and we know nothing of dating. The illustrated items do represent a larger investment of labour and a slightly different grinding technique than the Talkote stone, but does this simply mean a different socio-economic origin and tradi tion, or does it also indicate that they were used for different purposes?

If left behind, all these grinding devices would of course be preserved in an abandoned settlement.

Production of cooking oil

Information was gathered about one type of cooking oil, namely oil from the znz-tree fruits.

It was found that oil processing devices are not present in every household, but in two or three places in several of the villages under survey. People will come and use their neig hbours’ or relatives’ oil pressing device, if they don’t have any of their own. Only one family was questioned regarding the labour process, but their description was verified by others who knew.

The work was described as follows: in September or October, one or two will go out and collect wz-seeds under the znz-tree in the village. The tree belongs to the village at large. They will do this from three to five days. In total, 5-10kg of znz-tree seeds are gathered.

The seeds are left to dry in the sun for a week. They can be kept from three to five months. When the women have time, they will thresh the seeds in the vamgediya. It would take one woman about one and a half to two and a half days to thresh this quantity of seeds (probably only part time work is referred to). The following day she will winnow the seeds. They are subsequently boiled by one person and pressed by two of them. This will take approximately one and a half days.

From this quantity of seeds five to ten glass bottles of oil (containing approximately 0.9-11.) can be made. It can be kept for three or four years. Oil for medical purposes could be kept for five years. This household consisted of eight people. Ten bottles were not sufficient for them, so they had to buy addi tional coconut oil.

The oil-pressing device, named mi tel hindina pattalaya, is a log from the milla or buruta tree, divided lengthwise and pierced with holes at one end, in right angles to the cut (see fig. 18:24). A stick is thrust through the holes. The log is placed with one end in a natural bifurcation of a tree, about 0.8-lm above ground and the stick at the other end is sup ported by two forked branches, sunk vertically into the soil. Between the halves, a long, flat, basket-like device is placed, named a paha. The znz-tree seeds are put into the basket. A third stick is stuck into the ground, close to the tree. A string is pulled over the stick, wound twice around it. The other end of the loop is pulled under a fourth stick, which is put under the log with the string stretching over it. When the fourth stick is pulled downwards, towards the third stick, the two halves of the log are pressed together, thereby squeezing out the oil of the seeds into an earthen pot laced under the paha. The mi tel hindina pattalaya keeps from five to seven years. A similar device is described by John Davy at the beginning of the 19th century (Davy 1983 (1821):210).

Preservation of meat

Goat’s meat, was the only meat from domesticated animals preserved in the household. Surplus meat was also preserved from the wild animals caught - buffalo, elk, deer and wild boar.

Regarding goat’s meat, it was reportedly cut into slices and dried above the fire, on the dummassa, for a few days. The dummassa is a rectangular or circular frame, made out of "any kind of wood", the same material forming a net in the middle, similar to a loose two-shaft fabric weave. After being dried and smoked above the fire, the meat was put into a bag and hung above the fire. The smoke from the fire prevented insects from attacking the meat, which could be kept for five months. If the meat was put into a bag filled with ash, it could be kept for a year.

Another informant said the meat of wild animals was cut into slices, dried above the fire on the dummassa, and either put into bags and hung over the fire, or kept in pots filled with ash, where it could be kept up to one year. One former hunter, 81 years old, said he had met Vaddas in the Polonnaruva district 60 years back. They used honey for preserving meat.

Parker writes of the "Wanniyas" and hunters in Sri Lanka at large, that they used to dry surplus meat on "a rectangular stick frame, over a slow fire,...” (Parker 1984 (1909):50).

The pot of ash might make the storage of meat arch- aeologically visible. The most important fact however, is that it is possible to keep meat for up to one year, in the prevailing climate, through methods that are easily practised in a household. This is considered to be mostly women’s work.

Preservation of fish

Surplus fish is dried for two or three days above the fire, on the dummassa, as is the meat (see fig. 18:25). It is then put into a bag and hung from the roof above the fireplace. With

Figure 18:24 A m-oil pressing device

(mi-tel-hindina-pattalaya) in a home garden in Kayamvala village. When the stick in the forefront is pressed down, the two logs press out the oil from the mi seeds in the basket.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

larger fish, the head and entrails are cut away. In this way the fish can be preserved from three to six months.

One informant said that 50 years back (when he was yo ung) dried fish was kept, mixed with ash, in large earthen pots. The fish could be kept for one and a half years.

This again is considered mostly women’s work. Preservation of milk

Nowadays the milk is mostly sold. What is kept is most often given to the children, for immediate consumption, or used for cooking sweetmeats. It was stated that a buffalo would give three to four litres of milk per day during the rainy season, but not more than one and a half to two litres during the dry season (if it could be milked at all).

Two milk processing techniques, the making of clarified butter and curd, are still being practised. Clarified butter en ables storage for a longer period.

The household that used to make clarified butter kept buf

faloes. They described the process as follows: The buffalo is milked and the milk boiled. When the milk is cool, the fat at the top is removed. It is kept in the nabiliya (rice-cleaning, earthen basin) for three days. Then a wooden, pestle-like de vice, the mate, is used to stir it into butter. The butter is melted and the liquid poured into the clay vessel, or glass bottle, taking care to leave the protein containing lees. The clarified butter is used in curries, for example.

The mate in this case was fashioned out of one piece of gansuriya wood. It was made in the household, using a knife. It was 0.34m long, the handle end 0.04m in diameter and the stirring end 0.07m.

Curd was also made out of buffalo milk. The milk is boiled, then poured into an earthen basin, the kiri hattiya, and left overnight. It has to be eaten during the following day.

This is considered women’s work.

Preservation of chilli and wild plants, for beverages

Chilli is dried in the sun in the courtyard, directly on the ground.

Wild plants collected for preparing beverages are hung to dry from the roof inside the house, or in the verandah.

Preservation of deer, elk and goat skin

The skin of the deer or elk is used for making footwear - sandals, which are worn in the swidden field after the burn ing, to protect the feet.

The skin is cut from the flesh with a sharp knife. It is put out in the sun to dry for three days. It is fastened to the ground by wooden pegs, so that it stays flat. The inner side of the skin is not cleaned in any special way, but used as the sole of the sandal. This is considered men’s work. Goatskin is used for the women’s New Year drums. It is dried in the household, like elk skin. It wasn’t made clear whether the processing of the hair and fleshy part of the hide is different. Deerskin is also used for drums.

Figure 18:25 Fish preserved by drying on a wooden frame

(dummassa).

STORAGE

We will first consider storage of primary products from the vegetable kingdom. Most important, from our point of view, is the storage of grains. A range of grain processing stages in storage have been documented in different cultural and en vironmental settings: as sheaves, as ears, as unhusked grains, as husked grains, as pre-boiled, husked grains, as flour, as bread, or other processed items such as beer and malt.8

Starting by identifying the various purposes for which grains were stored, four very obvious factors come to mind: for household consumption and further processing; for the next season’s sowing; for selling or barter; and for payment of taxes or rents.

One quality which might concern the buyer, or tax or rent-receiving institution or households, is the germinative potential of the grains, which makes their further use a matter of choice - either for sowing, or further processing and con sumption, or for selling back to the cultivator as seed, or food, late in the season. During this study we found no indication of different storage for seeds meant for sowing.

In Talkote we were told the grains were stored for the household’s own consumption and for sowing. Sometimes part of the produce was sold. This wasn’t because of a surplus, but because cash was urgently needed, and grains most often had to be bought at the end of the season. The selection of seeds for sowing, and if the seed corns were specially treated before sowing, remains to be documented.

To estimate how much of the harvest a cultivator needed to store for the next season’s sowing, we must have a notion of return per area unit. This varies with different grains and seed quality, and also because of different techniques, water av ailability etc.

Based on accounts of the amount of seeds sown and the return on a given acreage, we could conclude that the ratio of sown to harvested paddy seemed to vary considerably with different households. Regarding the traditional purana vi (pa ddy) varieties that one informant grew fifteen to twenty years earlier, the ratio of sown to harvested paddy was 1kg: 18-20. Then neither manuring nor transplanting was practised, ne ither insecticides or weedicides used. The Local High Yielding varieties (L HYV) he now uses give him a 24-26 return, he said.

The return from LHYV of another informant was 10-13.3, and according to him this was little different from five years back, when he used the purana vi.

Their respective statements might be in accordance with the factual reality, but the varying results must be caused by some difference in field practice, quality of the soil, or water availability; or even a difference in storage practices, influenc ing the germinative potential of the seeds. No indications of a difference in grain storage techniques have come to our notice however. This is probably a good illustration of the limitations of a questionnaire, as compared to actual field participation. That traditional wet-rice cultivation techniques do give a varied return is indicated also in the literature/

For us, it is most important to establish the return of the purana vi, in contrast to the hill paddy and millet. Millet poses a special problem: sown in grains, but harvested and stored up to food preparation in the form of ears.

In Talkote, paddy is cut low, with much of the straw taken from the field. The whole harvest is threshed by buffalo-tram pling. It is stored as grain. The final husking however is done ‘meal-wise’, by pounding in the vamgediya. We saw very small portions of husked paddy being stored, and then only for a short time in flawed earthen pots which here found a secon dary use.

On the other hand, kurakkan and similar dry grains such as idal iringu (sorghum) and tanahal (Italian millet) are cut just below the ear, and stored in this form. ‘Threshing’ and husk ing takes place at the same time, ‘meal-wise’, in the vam gediya. Meneri (Panicum millet) is harvested with the sickle. Whether threshed before storage, and where stored, has to be further studied.

These observations are in line with Francois Sigaut’s remark that dehusked grains or groats of millet and rice can be kept for only a few hours, making it necessary to process them daily (Sigaut 1988:5).

It is in fact, a question of wider significance, as Sigaut claims. The difference in storage between the processed millet and rice, and the wheat, barley or rye flour is of primary importance for the history of machinery. The possibility for every household "in temperate climates" to keep the milled flour made European development of bigger mills profitable, says Sigaut; whereas the fast deterioration of millet and rice prevented a similar development in areas dependent mostly on these grains. He further mentions parboiling, as practised for example in India, to make husked or groated rice more du rable (Sigaut 1988:5).

The extremely short time limit given by Sigaut must be questioned. The women in Nagalavava gammandiya said the freshly ground flour of kurakkan tastes better, but that it is possible to store ground kurakkan up to three months in an earthen pot covered by a cloth, before insects (like the gulla) destroy it.

As an argument favouring the fundamental difference be tween the grains, Sigaut states that millet continued to be pounded with mortar and pestle in western France well into the 19th century - though water-and-windmills were as com mon there as in other areas of France (Sigaut 1988:5).

We could find an alternative explanation if we assume that millet cultivation wasn’t integrated with the market economy. Would it have paid to send the millet to the mechanised mills? Or did millet fit into the individual household’s yearly cycle of labour, as one of many minor, combined ways of finding a living? This seems to be the case in the swidden cultivation of millet in the Sigiriya area (see above). The wheat growing regions of northern India further indicate that the big Eu ropean mills are not just a result of the crops grown.

Vi bissa

The traditional structure for paddy storage in Talkote is the vi bissa (see fig. 18:29). The terminology of grain storage struc tures is a bit confusing also when consulting what has been written by people who have seen the structures they describe. Coomaraswamy talks of the bissa as a special type of small granary, found in the Kegalla district - "a cask-shaped wattle and daub erection on stone pillars, whitened with kaolin and covered with a heavy thatch, standing near the house but not forming part of it (Coomaraswamy 1956 (1908): 116).

Coomaraswamy states that otherwise the grain was stored in the atuva - a term that in Talkote was used only for dry grain storage structures. Ashley De Vos, too doesn’t make any difference between paddy and dry grain storage facilities, but talks of them as storage bins named bihi - the plural of bissa (De Vos 1977:43). Coomaraswamy writes: "The granary (at uva), always raised on low stone pillars as a protection against white ants, was if small, built over some part of the inner verandah of the house; if large, as in the case of a royal store (maha gabadava), a pansala, or the home of a well-to-do or powerful man, it formed a separate building" (Coomaras wamy 1956 (1908):116).

That such superstructure storage could involve large, or many structures, is indicated by a statement in the Sammo- havinodini, to which W.I. Siriweera calls our attention. There it is said that in the Tissamaharama monastery "were always" stored a quantity of grain that could feed twelve thousand monks, for three months (Siriweera 1989:84).

We found no granary built on the verandah of any house in Talkote. In Nagala vava, the larger houses used rooms in the house itself for storage and the undifferentiated houses, of one room only, kept their produce in that same room. Previously, the village had storage facilities for dry grain, according to the informants. As Coomaraswamy’s statement indicates, as a way of distinguishing not only between superstructure and village level storage, but also the socio-economic position of different households within the village, this line of study is worth continuing.

In the following we keep to the terminology used by the villagers in our study area. The vi bissa consists of a floor built of wooden planks on six horizontal wooden posts, resting ca 15-30cm above ground on six stone slabs (one in each comer and one at the two opposite sides). The stones are sunk into the ground only to level the floor. In case wooden pillars are used as a foundation, they will be sunk about 30cm into the ground. Separate from the floor, there are in all six wooden roof-supporting posts: one in each comer and one on the two opposite gables. They are dug down into the ground to a depth of 45cm. They are connected by horizontal posts resting in a natural crutch which constitutes the end of each vertical post. The roof is made of palm leaf or paddy straw. In the latter case, it is termed ‘pandaleya\ Underneath it paddy straw meant for fodder is sometimes stored, on a loosely laid floor of sticks. The floor plan of the vi bissa measures ca 2.4x2.4m. The pillar diameter is ca 18-20cm. The height of the construc tion is 2.9m.

Under the roof, the paddy is stored in a 1.6m high cylindri cal construction, with a diameter of ca 2.3m. It is built of bundles of paddy straw horizontally piled one above the other, bound together by wickers (ibikatuval), forming a circular space which is successively filled with threshed, but not final ly husked paddy. When the height is considered sufficient, the vi bissa is sealed with a roof of bundled paddy straw - and thereafter plastered with a mixture of mud and cowdung. Its storage capability should be measured.

For future archaeological identification, let us hope that foundation stones were used and left in situ. The only other possibility of identifying a free standing structure like the Talkote vi bissa, in a non-burnt archaeological context, seems to be finding the postholes, where their spacing could tell us the difference from a dwelling house - but maybe not from the traditional hen coops on poles, which are also there in the village.

Figure 18:26 Rice in Talkote village is stored in the vi bissa. This is built with bundles of paddy straw and coated with a mixture of soil and cowdung. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer

.

Atuva