Food Procurement: Labour Processes and Environmental Setting

- ADMIN

- Aug 23, 2021

- 53 min read

EVA MYRDAL-RUNEBJER

"Thus in a sense, the history of the Island has been viewed in the main as the history of the activities of kings, while the life of the ordinary people and their economic pursuits have only attracted cursory attention. Not surprisingly, this over emphasis on political and religious history has led to a neglect of social history in general and economic history in par ticular. " (W I Siriweera, Department of History, University of Peradeniya).1

Irrigation and swidden: two technological complexes

It is a well known fact that Dry Zone subsistence peasants of Sri Lanka, dependent upon village based irrigation - that is, using rain-fed tanks - have to combine paddy cultivation with swidden cultivation, foraging wild plants, fishing and, to so me extent, hunting and trapping, to support their households.

To define the Lankan Dry Zone economy, focusing on the combination of small-scale paddy cultivation and swidden cul tivation, as seen today, does not however give us sharp enough tools for analysis of changing land use and subsistence pat terns in the past. This is not to say that the combined economy is a modern phenomenon. But in focusing on the combination, we lose sight of the varied implications of each cultivation activity as regards yield and organization of labour. Hence due attention is not given to the potential social implications of one activity dominating the other.

Viewing each cultivation activity separately, from the vi ewpoint of the cultural and social landscape created - to pographical setting, crops, traditional views on the disposition of land, seasonality, mobilization of labour (number of pe ople), organisation of labour (relation between those working the land and those having it at their disposal), labour invest ment (man hours), implements and helping aids, productivity area-wise, storage techniques and combined activities - differ ing practices and returns of irrigated and swidden cultivation respectively, are seen today in the study area. This difference is, of course, also what creates the peasant’s capability of combining the two cultivation techniques.2 It is also clearly apparent that the cultural landscape of wet-rice cultivation rules out some of the activities of the subsistence-oriented swidden landscape.

Figure 16:1 Aerial photograph, Talkote village. Scale 1:3500. Note the mixed wet-rice and swidden cultivation landscape. Photo: Survey Department

This implies that two factors with a direct bearing on the foundation of social organisation - that is, organisation, mo bilization and investment of labour, and productivity area-wise - differ in the two cultivation activities. At the same time, the ethno-archaeological study gave reason to hope that these fac tors could be archaeologically traced. Ecofact and artefact material from a modern settlement site of the kind we saw, as well as structural remains associated with cultivation activities, would indicate whether irrigated or swidden subsistence cul tivation had been practised. The case of commercially oriented swidden cultivation might also be posible to single out.

The presentation below should not be seen as an attempt to develop a static model, or a closed, neatly balanced system. It is based on an exploration of a tiny fragment of our material world and is an attempt to understand its limitations and op portunities - an understanding that is useful for a future discus sion of the archaeological material.

The Dry Zone, a spatial and temporal outlook

Presenting the villages under study, we might start with a brief temporal and spatial outlook of the Dry Zone.

John Davy’s description of subsistence cultivating "village Weddahs" of the Uva region in the second decade of the 19th century, gives (besides the biased view of a colonial civil servant of the 19th century) a picture of a materially im poverished people: "Their dwellings are huts made of bark of trees; their food, the flesh of deer, elk, the wild hog, and the iguana, with a little Indian corn, and corican of their own growing, the wild yam, and the roots of some water-lilies. They use, besides, honey and wax; and in times of scarcity, decayed wood, which, mixed with honey, and made into ca kes, they eat, not so much for nourishment as to distend the empty stomach..." (Davy 1983 (1821):88).

Parker gives his account and that of another Ceylon civil servant, Hugh Nevill, of the hunting/gathering/subsistence s- widden cultivating economy, chiefly in the Eastern Province and the Vanni area in the late 19th century: "The food of the Forest Vaeddas consists of fruits, roots of wild yams, and especially honey and the flesh of any animal they can kill, which are chiefly Iguanas, Pigs and Deer. All the Village Vaed das, and the Tamil-speaking Vaeddas (with the exception of a very few who are solely fishermen), and the Wanniyas eat the same food, and have in addition the small millet above-men tioned, called Kurahan by the Sinhalese the Indian Ragi(Eleusine coracana). This is grown in temporary clearings (termed hena in Sinhalese) made in the forest, all bushes and grass being cut and burnt off, but not the larger trees. After one crop, or sometimes two have been taken off the ground, the clearing is abandoned and allowed to be overgrown once more with jungle, and is not re-cultivated until from five to seven years have elapsed. In their clearings, which are exactly like those of the Sinhalese, are also grown a few red Chillies and Gourds, and sometimes a little Indian Com, and a small Pulse called Mung (Phaseolus mungo). A very few Village Vaeddas and Wanniyas who live in suitable places for it grow and irrigate a little rice, which the Forest Vaeddas are now learning to cook and eat when they can procure it”.

Dried and ground seeds of the Tree-fern (Cycas cirinalis) and the bud of unopened leaves at the crown of the wild date (Phoenix zeylanica) are also mentioned as eaten by the Vad- das, Vannis and Sinhalese villagers (Parker 1984 (1909):50- 52).

Reading A.C. Lawrie’s A Gazetteer of the Central Pr ovince indicates that the situation in our study area, at the end of the 19th century, was far removed from a prosperous system of combined swidden and paddy cultivation. Of the 22 pur ana villages of Inamaluva Korale (where most of our field work so far has been concentrated) mentioned by A.C. Lawrie in 1898, three were abandoned villages at the time of his survey and two were explicitly mentioned as not doing paddy cultivation. Of 17 villages associated with functioning tanks, only one was said to cultivate paddy every year, whereas 13 were explicitly mentioned as not doing so for lack of water (three "seldom” or "infrequent”, one "once in ten years", nine "once in three or four years"). Swidden cultivation is explicitly stated to be the support of two of these nine villages cultivating paddy "once in three or four years".3

We should of course be careful not to take it for granted that the pre-modem situation for subsistence cultivating fa rmers was similar to the colonial. We might, for example, ask if there was an economic decline in the Dry Zone, from the end of the 17th century to the mid-19th century. If we read Robert Knox’s description of the one-time centre of the Ra- jarata civilization - the area around Anuradhapura - we get an impression of habitation and irrigated agriculture, though at a lower level. Knox says about the situation in 1679:

"To Anarodgburro therefore we came,...which is not so much a particular single Town, as a Territory. It is a vast great Plain, the like I never saw in all that Island: in the midst whereof is a Lake, which may be a mile over, not natural, but made by art, as other Ponds in the Country, to serve them to water their Com Grounds. This Plain is encompassed round with Woods, and small Towns among them on every sid- e...Being come out thro the Woods into this plain, we stood

looking and staring round about us, but knew not where nor which way to go." (Knox 1981:353).

About the health situation he says: "The Northern parts are some what sickly by reason of bad water, the rest very health ful." (Knox 1981:96).

In the mid-19th century, Tennent gives a different picture of desolation reigning over the plains (Tennent, J. E. 1977 (1859):361).

Until a careful investigation is carried out regarding this late historical period, nothing definite can be said; but when handling our ethno-archaeological material we should again think about what is materially given (in this case, what security a subsistence economy could have, given the environmental and technical situation) and what is historically specific (in what way the social set-up and forces from outside might have influenced the situation).

Presentation of the study area

Three villages around Sigiriya formed the core of our study, chosen to cover different aspects of rural life that might have been of relevance also at the time of the formation of the (historical period) archaeological record. The choice was ba sed on interviews by the SARCP Village Inquiry Unit in 1988 (Wickremesekara 1990:161-166).

One is Talkote village. In 1981 the village had a population of 581 persons.4 The cultural landscape in and around the village is formed by irrigated agriculture, and still much of the seasonal work is organized around paddy cultivation and what was found to be related to it - that is, fishing in tanks and cow and buffalo farming. The earliest known mention of Talkote is on the Mirror Wall, in an inscription from the late Kandyan period, the 18th century.

It has various minor monastic remains within its present boundaries and a minor test excavation was conducted at one of the sites in 1989. The former village site is now abandoned. The desertion started 50 years ago.

To develop our ability to gain information of settlement sites without large scale excavation, sites such as these might be used to detect activity areas. Intensive field-walking could be done, armed with previously culled knowledge of housing and storage facilities and having the villagers to inquire from; and coring for soil samples; or using radar and mapping pot sherd concentrations to detect garbage pits, or dwelling house floor areas. If just field-walking is done, the researcher must be conscious of the fact that the habitation site has gradually shifted a short distance, without haste or disorganization. That is, whatever could be useful for the new house moved away without cost of great energy, including, perhaps, grinding st ones and foundation stones for storage bins.

Figure 16:2 Site location map.

This fact has a significance beyond the pedagogical prob lem. There is a possibility that many of the pottery sites that have been found might be the result of such short-distance shifts. So the artefact material and structures that give ho usehold-level information on production processes, patterns of storage and household wealth, might have an extremely de lusive and fragmentary character, consisting mainly of wasted pottery and floor areas invisible on the surface. This is an important difference, compared to abandoned elite-structures in the area, where more durable and not easily movable build ing material has been used.

A very large settlement site is situated in an area named Tammanagala, at the southern end of one of the larger village tanks (Ihalavava). This settlement site was partly excavated in 1990. Talkote, then, is the most important village from an educational point of view, where we can work in parallel with ethnographical and archaeological studies.

Another village is Diyakapilla, dependent mostly on swid- den cultivation and related activities, such as foraging wild plants, collecting honey, hunting and trapping and, to a lesser extent, paddy cultivation. In 1981, 132 persons lived in the village (Wickremesekara 1990:162). The tank is situated in the neighbouring village Kosgaha-ala, with which the Diyakapilla cultivators share the irrigated area. Some paddy is also cul tivated by building weirs in a little seasonal stream, directing the water to neighbouring fields. The village is situated in scrub jungle and according to Lawrie, was a new settlement from Sigiriya, with two and a half acres of paddy land, registered in 1878. There is no mention of the frequency of paddy cultivation at that time (Lawrie 1990 (1898): 170).

The dispersed village, which is now typical of the new settlement areas based on large tank irrigation schemes and which is a recent development in Talkote, could not be treated simply as a modem phenomenon. Ashley De Vos mentions the type, in his article on rural architecture, as typical of the tradi tional rain-fed village (De Vos 1977:43-44). That is, a settle ment more dependent on direct precipitation than on stored water for its cultivation activities. In his description, this type of village has the houses located along the village path, or road, in large and scattered home garden plots, the paddy fields located close behind and the chena fields farther away.

We might ask if the dispersed village pattern is the tradi tional form of new settlements in areas outside those intensive ly cultivated by irrigation, even before re-colonization started in the 19th century.5 Diyakapilla village might then be a modem example of a dispersed traditional village of this type in the survey area.

With past experience of field survey, we can formulate the question: to what extent before the modern era was it at all possible for a central authority to keep pace with settlements of this kind? Probably only as long as locally based admi nistrators were ready to support the central authority.

With fragile remains of a humble settlement and a very minor change in topographical features (although, if swidden cultivation was practised, there probably were significant cha nges in the original vegetation) it is difficult to trace these settlements in a field survey. We shall now discuss a tech nological complex that might fit into this settlement pattern and way of life.

The third more intensively studied village in our survey area is Nagalavava. It had a population of 330 in 1981 (Wick remesekara 1990:164). The village is situated in a cultural landscape established by irrigated agriculture, in close pr oximity to a cave monastery. The villagers nowadays however are mostly dependent on swidden cultivation. Lawrie states that paddy was cultivated here only once in ten years, at the end of the last century. The villagers traditionally served as messengers and drum-beaters (Wickremesekara 1990:164, a- nd Lawrie 1990 (1898):171). That is, in contrast to Diyaka pilla, they have been closely related to the paddy-cultivating economy, but in contrast to Talkote, they are integrated into the social network as a serving community.

A small part of Nagalavava village (seven households) still retains features of a traditional cluster village, and many of the traditional techniques of food preparation and storage are still practised here. One theme of study was traditional rural house building techniques, organization of space for various activi ties within the house and compound and the village as a whole, and its setting in the cultural landscape. The burial ground was considered part of the cultural landscape.

Another theme was traditional medicine - the collection of material and techniques of preparation, as well as storage. Traditional measurements were documented, including the m- aking of various measuring devices.

This characterization is to be viewed only as a help to focus three different rural possibilities.

To cover other aspects of rural life as well, we went to six other villages in the area.

Kayamvala village was visited to study traditional mz-oil pressing for household consumption. According to the 1988 village survey it is a new settlement, formed in 1953 by people from Sigiriya. In 1988 there were 304 residents (Wickre- mesekara 1990:163).

Pidurangala village, with 247 inhabitants in 1981, was visited to discuss hunting, trapping and the collection of wild plants. A well-known elder, a former hunter, is now living there. Pidurangala village itself is mainly a paddy cultivating village. At the end of the 19th century it cultivated its fields once in three or four years. A monastery dating back to the 5th century is situated nearby (Wickremesekara 1990:165 and La wrie 1990 (1898): 171).

Kosgaha-ala village, situated below Vannigamayavava, has no motorable road. It was visited to discuss questions of transport. According to our informants, the present village was established in the 1940’s-50’s by reoccupation of a former settlement site of unknown origin. It is not mentioned in La wrie and not discussed by Wickremesekara. The villagers sh are Vannigamayavava with Diyakapilla. Paddy cultivation is combined with cattle rearing, herding cattle from Pidurangala, commercially oriented swidden cultivation, some hunting and trapping and various minor entrepreneurial ventures.

Ilukvava village, recently named Mahasengama, was visi ted to discuss the collection of wild plants with an elderly woman; and a specific trapping device with a swidden cul tivator. We were also able to visit a swidden field during the kurakkan harvest. In 1981, before the new village was fou nded, it had a population of 69.

The village is not mentioned by Lawrie. The Village In quiry Unit states that paddy cultivation, swidden cultivation, hunting and to some extent cattle rearing, constitute the basis of subsistence (Wickremesekara 1990:163). In 1991 we got the information that the original gammandiya of the village had been abandoned in 1942. A new location was chosen, closer to Sigiriya village. In the 1980’s the new village of Mahasengama was founded by governmental initiative. The original gammandiya of Ilukvava is now used for swidden cultivation. It could, like the abandoned gammandiya of Tal kote, be used for ethno-archaeological studies.

Udavalayagama was visited to study the aba (mustard) harvest in a swidden field. Lawrie states that paddy cultivation is infrequent and that the inhabitants suffer much from parangi (Lawrie 1990 (1898):173). The Village Inquiry Unit mentions that paddy cultivation is supplemented by chena cultivation. The village had 219 inhabitants in 1981 (Wicremesekara 1990:166).

Digampataha village was visited to interview a Tamil fa mily of traditional stone-cutters (the only traditional stone-cut ters known in the area today) and the owner of hunting dogs. Lawrie mentions that the fields of the village, at the end of the 19th century, were "seldom sown, from want of water.". The Village Inquiry Unit states that hunting and swidden-subsis- tence cultivation constitute the most important means of li velihood in the village today; the tanks are utilized for fishing. The village had 898 inhabitants in 1981 (Lawrie 1990 (18- 98): 170; Wickremesekara 1990:162).

Sigiriya village was visited to interview a stone-cutter who learned his skill by working for the Archaeological Depart ment, and who replaced the Digampataha stone-cutters as sup plier of grinding stones etc. in villages around Sigiriya. Lawrie describes the end-19th century situation: "The people suffer much from want of nourishing food and from parangi and aramana." (Lawrie 1990 (1898): 171). Sigiriya was not visited by the Village Inquiry Unit.

We worked within a radius of 5km from Sigiriya rock.

THE QUESTIONS AT ISSUE

The household, a unit of reproduction.

In the ethno-archaeological inquiry we wished to define the basic unit that would ensure the physical reproduction of rural society (here we use the word ‘reproduction’ in the restricted physical sense). By this we don’t just mean raising children, but acknowledging the importance of human labour in a non mechanized society, the support of every individual. This would, of course, also be a unit of consumption.

The basic unit of reproduction was defined as the hou sehold.6 That is, people who live together and contribute pro ductive and reproductive labour to the unit’s survival.

Human labour was seen in the context of the individual household. Our questions were: what does human labour in a household accomplish? By whom? When? Where? With what equipment? And for whom?

To understand the whole production process of wet-rice cultivation, for example, the household in most cases is too small a unit. There are examples of a single household build ing a small seasonal weir in a seasonal stream, to release water to minor wet-rice fields; but even the smallest tanks (termed vav kotu by the villagers in our study area) had at least three families as builders and maintainers.

At least three labour processes relating to wet-rice cultiva tion usually involve the exchange or hiring of labour, harvest ing, stacking and threshing. In most cases therefore, we could assume that wet-rice cultivation of one field directly involves several households.

Also, regarding reproduction in its primary meaning of procreation, the individual household is, of course, dependant on a larger social unit.

But to understand what constraints and material possi bilities exist in relation to non-mechanized wet-rice or swidden cultivation in the area, focus on the household as a unit of reproduction is rewarding.

The household in an archaeological context

The question of identifying a Lankan household in the ar chaeological context has not yet been discussed or attempted in the field. As a starting point therefore, we should take the modern social anthropological studies of rural Sri Lanka.

What then constitutes a Lankan household today in the ‘traditional’ rural context? And if we test this pattern on an archaeological site, what traces would be significant?

Nur Yalman has defined the basic unit in the Kandyan rural highland as the commensal unit, the nuclear family. He em phasizes the economic independence of the nuclear family - where food preparation, consumption and storage are or ganized by the wife and husband, and where each married adult is also a single unit in relation to the rewards of labour (Yalman 1967:100, 102). We can take this as our starting point, as it gives us two archaeologically visible features: the hearth and storage facilities.

But what about the house as such? There are examples of a house being inhabited by several ‘commensal units’. In Nur Yalman’s study of a highland village, it is pointed out that newly formed couples may choose to live in either parental home during the first years of their union (Yalman 1967:104, 118-119).

This is not to be confused with the fact that the couple could choose to work the land of either family - the wife’s (binna marriage) or husband’s (diga marriage). They need not live in the same house, or even in the same compound as the parents. The arrangement has significance where land-owner ship and inheritance are involved (Yalman 1967:126).

E.R. Leach points out that in his study area, the young husband will pool labour with his father/father-in-law while he lives with them. He notes: "Individuals who lived under the same roof nearly always worked in the same team; but in dividuals who lived in the same compound in different houses very seldom worked in the same team." (this relates to the exchange labour teams that are formed) (Leach 1961:265). He further notes that in a diga marriage it is likely that there will be no separate storage of grain, though the couple might live in a separate house in the compound (Leach 1961:270). If they stay in the same house, we shall find two hearths and one granary there.

The other possibility is that the son or son-in-law will receive grain on a share-cropping basis from the land still in possession of the householder, and keep it in a separate store (Leach 1961:270).

Here the number of hearths within the house indicate a household with additional labour capacity. Each couple con sumes its own share, but from a common source of labour investment.

Nur Yalman says of families not possessing land, that the different commensal units in a house might act independently in the production process and can have a quite different ec onomic status (Yalman 1967:119).

In this case, the house as such would neither constitute the physical base for a unit of consumption, nor a unit of produc tion. He has not approached the question from the standpoint of reproduction however. It is possible that this arrangement could also liberate the young woman from certain child caring duties and hence give her a better chance of taking part in productive work outside - increasing the food supply.

Even a house with separate consumption and production units (several hearths and granaries indicate this) might still have a common, enhanced production potential. This, of co urse, has implications from a reproduction point of view. It seems possible, although it should be studied in the actual Lankan context.

In our study we also met an extended household of a different kind. Two aged parents were living with their son and his family. It was not a permanent arrangement, as they later moved to another son in the village. As in the case of the new young couple, they had a separate hearth, but they could con tribute very little to the productive labour of the household, although they were fed from the land their son cultivated. We could however follow the earlier argument and assume that this arrangement could have an overall effect on the hous ewife’s productive capacity. Unmarried, grown-up sons and daughters contributed to household labour, but they would not be visible in the ar chaeological record, unlike the newly married couple.

As the size of a household is constantly changing with the family life cycle, it might be argued that the number of hearths and granaries in one house would have no significance from a structural, socio-economic point of view. The individual hearth is the feature that signifies the basic unit of reproduction. But, as noted above, several households living under one roof might stand in a different supportive relationship, compared to families living in different houses. Though we might not be able to draw any conclusions in terms of the labour capacity of ‘a house’ based on the number of hearths, these different possibilities should, however, be kept in mind.

To sum up, it would be possible to find the modern unit of reproduction in an archaeological record. Focusing on a house, we could also distinguish between different reproduction units which support one another.

The case of double hearths and granaries would indicate two households (separate consumption and probably separate production units), whereas two hearths and one granary would indicate two consumption units but one production unit (the case of the aged parents, for example). The latter should then be treated as one household (one unit of reproduction), as the basis of reproduction (productive work and its reward) is com mon.

No direct conclusions could be drawn however regarding labour capacity or organization of labour, as the work teams for exchange labour, land ownership and share-cropping ar rangements are not directly visible in the archaeological ma terial, at least not at the single habitation site. It might be inferred from wealth studies of an entire village site, of house space and household goods.

Food Procurement Labour Processes

The various food procurement labour processes were divided into 11 groups, with a separate form drawn up for each of them. The groups were: irrigated low-land, home garden, swidden and permanent dry land cultivation; cattle, buffalo, goat and poultry farming; hunting and trapping, fishing and foraging for wild plants and other forest products. Added was a form concerning the use of buffaloes and bullocks as dr aught animals, focusing on ploughing, transport, threshing and drawing water; and another form focused on building, maintenance and management of irrigation facilities. The in tention was to document each stage in the labour process by means of the questionnaire. Agriculture

Regarding agricultural work, the study defined each stage from the selection and preparation of the field, to long-term storage of the produce - as regards area of land, time of year, number of work participants, their age and sex, their relation to the household, work days per year and the tools and other devices used in the process. The location of threshing and storage was also sought. We discussed yield per unit area and the amount sown, as well as the total amount of long-term storage for consumption; and sowing and selling patterns in a two to three-year time frame. The reliability of interview data concerning these last mentioned questions is discussed below.

Livestock tending

Turning to livestock tending, our focus once again was on human labour in terms of location, work days etc. (as outlined above and equipment for herding and tending the animals in their daily and seasonally varying life cycles, as well as their individual life-cycle (from calf to milch cow to meat, for example); what labour goes into keeping them alive, extract ing work or produce from them, and their returns. As regards produce extracted, we recognized eggs, milk, manure, meat and hides. In the field, we found that animal horns were also used. We asked especially about further processing of the produce both for immediate consumption and preservation and storage. From kiri (milk) to di kiri (curd) or gitel (clarified butter from cow milk), or from fresh meat to sm oked meat hung above the fire, or kept in ash. Also what storage vessels or other devices were used in the process, and where they were kept.

Hunting, trapping, fishing and foraging

The questions were the same for hunting, trapping, fishing and foraging: which species were caught or collected, pr ocessed and stored - where, when, by whom and with what equipment.

Documentation of tools and implements

Our second line of study was the documentation of tools and implements and other devices used in the labour process. We focused on describing the physical properties of the item - that is, the material, size, weight and shape. We also sought answers to such questions as by whom it was produced, ap proximate cost, if bought, or time spent if made in the household, by whom and how often repaired, how old the given item and its general span of usage, also by whom the particular item is used and for what purpose. In fact, all those additional questions that will not be directly answered while studying archaeological material.One aim of this study was to get an approximate notion of the amount used of the various raw materials necessary for food procurement - for example, iron. At the present stage we consider our source material too scarce to allow for any ge neralized conclusions.

To make a comparison between present day consumption and that of pre-modern settlements to be excavated, a com parative metallographic analysis of present day and archaeo- logically found material must also be undertaken.

In focusing on a given item, we happened on some extra information: the karaka used for fishing was also used as a protective cage for the chickens at night; the pan katta could be used instead of the kurakkan katta in dry crop harvesting - although our informants didn’t think of referring to the pan katta when asked about tools used in the kurakkan harvest; a malu muttiya (large pot) that we documented gave rise to the information that such pots were previously used for storing dried fish mixed with ash, but that nowadays they were used for cooking food for almsgivings. This particular pot was broken and used for short-term storage of husked rice.

This is a salutary exercise for archaeologists who think they can once and for all determine the detailed function of a given item. At the same time, the study underlined the fact that form and function are interrelated - you don’t carry water a long way from the well in a dish, if you have a choice; if you don’t have access to a kurakkan katta, it is the smaller pan katta, not the larger dakatta that you prefer to bring to the chena, for the ear-by-ear harvesting of kurakkan. And usages totally alien to the purpose for which the item was originally made could, probably, in the majority of cases, be classified as marginal - but more important, as indicators of changing con ditions of production.

By chance we found the last surviving yota (water-drawing device) in the village of Talkote. It was functioning as a door to a dwelling house at night and as a see-saw for the children by day. Since the introduction of water from the large irrigation scheme, theyota hasn’t (yet) been necessary, and hence made useful in another context. It could be argued that this points to the regularity and logical coherence of social and material life, thus the possibility of interpreting and generalizing from an archaeological standpoint.

Figure 16:3 Karaka (fishing device) used as a chicken coop at night. The birds range freely picking food during the day.

Talkote village. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Documentation of the setting of the labour process

Our third line of research was the site of the labour process. Labour here is to be understood both as reproductive work (as, for example, food processing) and productive work (such as ploughing).

Therefore we recognized 10 major areas of study: the dwelling house with its compound and home garden, the ani mal pens, herding areas, irrigated fields, tank bunds and other irrigation facilities, chena (swidden) fields, hunting and forag ing grounds, water sources for fishing and stone quarries. None of the iron production sites has any parallel in the ‘live’ area.

The purpose of this study was threefold. First, we wanted a notion of what traces the various activities could possibly leave in and on the ground; secondly, we sought to recognize the topographical setting of each activity, where any such pat tern emerged; third, we wished to get a more general under standing of what determined the location of the labour process, what was ecologically and topographically its optimal setting, so to say.

It is obvious that the various labour processes will in fluence the natural surroundings in different degrees - from the construction of the tank and paddy fields, creating a new landscape, to the foraging of wild plants, which activity might not be traceable in the terrain. Many locations will be similar for different activities. Chena land, for example, is also used for grazing, foraging and trapping. It is also important to note that the material can’t be interpreted in a static way. Expanding irrigated agriculture, for example, will reduce the hunting ground. So the labour processes have to be seen in relation to other contemporary activities.

Land use, activity areas and archaeological visibility

During the field survey campaigns in 1988-1991, a complex pattern emerged as regards the location of settlements and land use through time.

Present day Talkote has six at least partly functioning tanks within the present village boundary. The gammandiya site is not by the bund or below the tank, but beside a crossroad west of the main water course between the two largest tanks within the present boundaries. This might mark a settlement pattern answering to the inclusion of several tanks within the economy of the village. Pahala Talkote (mentioned by Lawrie as an abandoned village) west of Pahalavava was, according to the village inquiry 1988, the site of the village before the gamman- diya of yesterday (Lawrie 1990 (1898): 173 and Wic- kremesekara 1990:165).

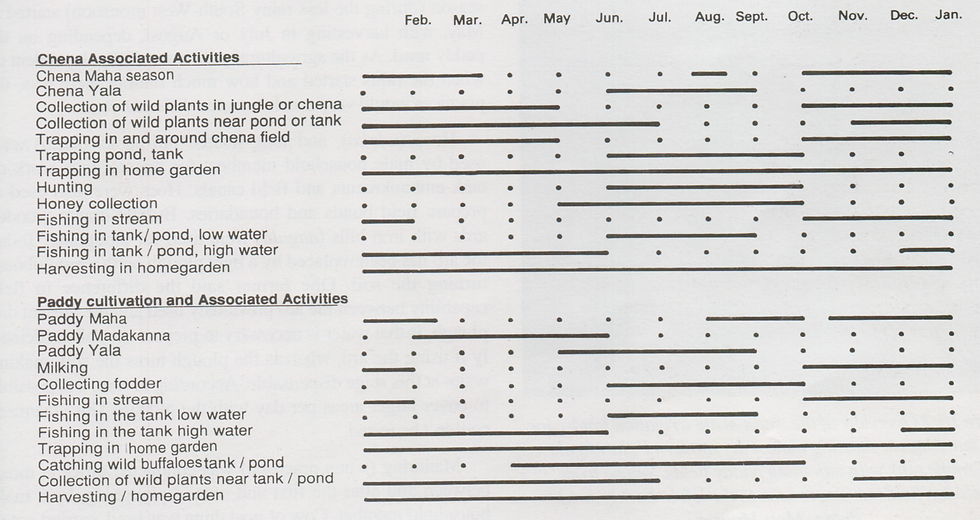

Figure 16:4 Seasonal land-use pattern.

There is a complex pattern of changing land use through time, pointing to various possibilities of utilizing the environ ment. Within the Talkote-Pidurangala boundaries there now is a chena on an abandoned paddy field, in a former tank bed (the abandoned Halmillavava) in the command area of another tank still in use (the 20th century Pidurangala temple tank). There is also a chena on a former minor tank bund built on a previous settlement site (SO .47). The bund itself is made up of cultural layers from its earlier existence. The present temple tank bund is built on a previous settlement (SO .56), and also

bears the residue of earlier living. The site of Pahala Talkote village, mentioned in Lawrie in 1878 as an abandoned settle ment, is now turned into chena land (Lawrie1990 (1898): 173).

The various erections made for the religious superstructure (SO .30) sited on abandoned paddy fields below a tank bund, and the minor tanks themselves, some of which are still re membered in the oral tradition as being used by three to five families (as the Kotalahimbutugahavava) are other examples of a cultural landscape long in use and constantly changing. Though it is possible to arrive at a relative chronology for some of the sites, stratigraphies and accurate dating of the settlement sites, fields and tank bunds would be necessary for a detailed knowledge of how utilization of the environment has changed through time (for a thorough discussion of the Talkote settlement pattern see Mogren this volume).

In this context we might consider Robert Knox’s descrip tion - probably from the kingdom of Kandy :

Figure 16:5 Modern example ofchanging land use. Former Ilukvava gammandiya, abandoned in 1943. Now used as

chena land for aba (mustard). Land known to be very fertile.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

"And as I said before of their Cities, so I must of their Towns, That there are many of them here and there lie deso late, occasioned by their voluntary forsaking them, which they often do, in case many of them fall sick, and two or three die soon after one another: ...Whereupon they all leave their Town and go to another... Thus relinquishing both their Houses and Lands too. Yet afterwards,...some will sometimes come back and reassume their Lands again." (Knox 1981:353).

A situation which would result in a very complicated set tlement pattern for the archaeologist to analyse from a field survey only!

Focusing on the different areas where food procurement activities are carried out, we will discuss the archaeological visibility of those activities in field surveys and excavations.

Irrigated paddy cultivation, livestock tending, fishing

In villages like Talkote, where paddy cultivation today is, and according to our informants has traditionally been more do minant than swidden cultivation, we found livestock tending and fishing to be important associated activities.

There are many descriptions of wet-rice cultivation prac tices in Sri Lanka, more or less detailed as regards cultural landscape, equipment, labour investment, yield and division of labour between the sexes.7 Therefore we shall only present a brief overview of the technological complex of rice-cattle-fish, with focus on the labour process as seen in the study area.

Figure 16:6 Main seasons for various food procurement activities. They vary in time in relation to start of the rainy season and amount of precipitation.

With the Mahavali irrigation scheme giving greater year round access to water in some tanks, the High Yielding Va rieties (HYV) of paddy totally dominant and irrigated cash crops like onions and chilli becoming more important, the yearly cycle is now changing. A difference between the field systems of owners with and without access to the new irriga tion facilities has also been created. Therefore the following description, based on interviews with two households and the three former vel vidanes of the village, on documentation of material equipment and by field-walking, is a reconstruction of past usages in a fast changing environment.

In the modem period before the Mahavali irrigation sc heme was introduced, only locally based water sources were used and the local precipitation was crucial for all cultivation activities. This naturally determined the planning of the ag ricultural year. The most reliable cultivation season, according to our villagers, was the Maha season, starting in mid-October with the North-East monsoon.

Preparation commenced in August, with the maintenance work of tanks and field canals. Ideally, this work was collec tively undertaken by the cultivators of the fields below the tank, each cultivating household contributing labour in relation to their cultivated acreage. Fields were cultivated by the in dividual household (with additional hired labour, or exchange labour) in their capacity as owners, share-croppers etc.

Figure 16:7 Overview of the small-scale irrigation landscape in late August, showing almost dry modern Pidurangala

Temple tank with adjoining paddy fields. Smoke from swidden field burning is seen to the left in background.

Photo: Mats Mogren.

In Talkote village (depending on the variety of paddy used and the timing of the monsoon) sowing in the Maha season was done sometime before end-November, harvesting in Fe bruary-March. If there was water left in the tank, the peasants could also cultivate during what they termed the Madakanne season, sowing in February and harvesting in May. The Yala

Figure 16:8 Maintenance of the tank bund, late August, Talkote Pahalavava. Almost dry tank bed is seen to the left. Traditionally, each cultivator contributed work in relation to

the amount of land he tilled below the tank:

Photo: Mats Mogren.

season (during the less rainy South-West monsoon) started in May, with harvesting in July or August, depending on the paddy used. As the agricultural year was wholly dependent on when the rains started and how much rainfall there was, the practices would vary much between different years.

Hoes (udalla), and long-shafted bill-hooks (katta) were used by male household members for maintenance work on tank embankments and field canals. Hoes were also used to prepare field bunds and boundaries. Buffalo-drawn wooden ards with iron bills (nagula) were used for ploughing. Today the ard has been replaced by a light plough, with a mouldboard turning the soil. One farmer said the difference in field capability between the ard previously used and the present day plough, is that water is necessary to prepare the soil sufficient ly if using the ard, whereas the plough turns the soil, making water at this stage dispensable. According to him, it is possible to cover larger areas per day with the plough. This statement couldn’t be tested.

Manuring (when practised) was conducted thrice at most, between and after the first and second ploughing, by a male household member. Cow or goat dung was used, carried out to the field in a basket. Buffaloes and hand-drawn levellers (po- ruva) were used before sowing, to even the surface, obtaining an even water level throughout the field.

Figure 16:9 Ploughing of paddy field now watered by the Mahavali scheme. Talkote village, late October.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

By making an opening in the field bund, water was sup plied through gravitation after the first and second ploughings and continuously after the seeds had sprouted. If water was scarce, a trough-shaped, swinging wooden device (yota) was used by the male cultivators in turn, at the end of the cultivat ing season, to draw water from the tank into the field canal and irrigate their individual fields.

For 10-15 days after sowing, the whole family, or at least the children, went to the fields every morning and evening, to scare off seed-hungry birds by screaming and clapping etc.

Weeding was done by hand, by the women, twice - first after one month, then after one month and ten days. Often labourers had to be hired for weeding a two-acre field, to supplement the household women’s workforce.

The paddy field was watched every night, from late Dec ember till harvest, by a male of the household, who used crackers and dried coconut palm flares to scare away elephants and other animals. The watching of swiddens was simul taneously undertaken. See below.

At paddy-flowering time in mid-January, the rice plants were often attacked by insects. Until about ten years back, a man of the household used to light oil lamps in a comer of the field, in the evening, to lure the insects away. This was con tinued for a week.

The threshing ground (kamata) was prepared in uncul tivated highland close to the fields, in February-March, before harvest, by either men or women of the household.8 Paddy was harvested with sickles (dakatta) by men and women tog ether. Often harvesting required labour to be brought in from outside. As the peak harvesting season was common to all peasants, labour might have to be hired. Often however the work was carried out through mutual help, with relatives and neighbours.9 Bundling and carrying these bundles to the th reshing ground was done by men.

After one day of drying, the harvest was threshed by buf faloes trampling the grain. They were led by men. This re quired both trained buffaloes and skilled ploughman. Not every household owned buffaloes. Additional labour is some times hired for this work. This may be a stage of work where power relations are manifest and re-established, although we could not document such aspects, given our few informants.10

The grain was stored in a closed container (vi bissa) built

Figure 16:10 The last yota (water-drawing device) found in Talkote village. Owner now uses it as a door to his house.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

of paddy straw, clay and cow-dung - provided sufficient yield was obtained to make building it worthwhile. Before cooking, the rice was hulled by the women of the household in a wooden mortar (vamgediya) and winnowed with a plaited winnower.

In paddy cultivation, the majority of tasks were considered male work. Weeding was exclusively done by women. Scaring the birds, preparing the threshing ground and harvesting could be carried out by either men or women.

Figure 16:11 Sickle with serrated edge used to harvest paddy. Talkote village. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Archaeological visibility of paddy cultivation

The irrigation constructions themselves, in terms of earth bunds, are of course wet-rice indicators. There will, however, be a problem of relating a given construction to a given settlement if the topographical location of the site does not give a clear indication. To calculate the capacity of a tank during the settlement’s time of occupation (and thereby infer possible returns) will be a further difficulty, as the tank bund may have been enlarged. These aspects, as well as identifying the fields and determining their acreage, will be dealt with in greater detail in the coming report on the archaeology of irrigated agriculture.

We noticed that rice is also grown without irrigation fa cilities. Paddy fields are sometimes introduced in low lying, flat areas, where water naturally collects during the rains, the bunds of the paddy field themselves acting as water storage devices. Ecofact remains from rice-plants (macro-fossils, pol len and phytoliths) therefore don’t by themselves indicate ir rigated agriculture.

With better knowledge of the paddy field weeds, however, we might be able to tell from pollen and other ecofacts of a settlement site if the rice-plants co-existed with plants thriving in long term, waterlogged conditions - conditions that would not be present in a rain-fed field.

The yield from rain-fed cultivation compared to irrigated agriculture should be discussed not only for a given acreage, but over time, as this is a form of cultivation even more vulnerable to local precipitation vagaries than the rain-fed tank.

Bryce Ryan describes the technique used in field prepara tion by paddy cultivators in Bulupitya village, Uva Province, in the 1950’s. Here, no ard is used in field preparation. Earth is turned by hoes and the fields are ‘muddied’ by driving buffaloes over the land, after flooding it. Here, paddy cultivation comes second in importance to chena cultivation, and the peasants are totally dependant on the local precipitation for irrigation (Ryan, Arulpragasam, Bibile 1955:155). No similar practice was reported from our study area.

Macro-fossil paddy could, therefore, indicate various le vels of cultivation techniques. The ard-share (as compared to the hoe) would indicate the possibility of larger areas, as tilling is a faster process with ards than by turning the soil manually (Sathasivampillai 1967:198-199). The ard-share is a probable indicator of extended areas of paddy cultivation, when found in an archaeological context. As discussed below, we shall probably find ard-shares only in connection with ‘muddied’ fields.

Iron sickles are less certain rice-indicators, as they could have been used for harvesting certain dry grains as well (see below, under swidden).

Home gardens

What was similar though, in most of the predominantly wet rice or swidden cultivating villages in our study area, were the individual home gardens with their wild edible plants, coconut palms and fruit trees. Various minor crops were also grown here. At any time of the year there would be something to pluck, or harvest, from the garden.

The individual home garden is a recent phenomenon how ever in Talkote, which until 50 years ago was a cluster village with a common compound. In Nagalavava gammandiya there are still no individual home gardens.

Livestock tending and archaeological visibility

Poultry is kept to provide eggs and meat. The birds are sl aughtered by any male of the household, for festive occa sions. Hens and chickens receive very little attention in households which keep merely a few birds. A protected place is sometimes prepared for broody hens. Chickens are often protected under the karaka at night. A few, small, hen coops of palm leaves, built on wooden posts, are seen in Talkote. During the day the birds walk around freely, finding their own food. They are given water in the dry season. The picture is changing now, with richer peasants keeping somewhat larger runs.

The osteological material left on a settlement site is pr obably the sole indicator of poultry keeping.

The availability or not of water also determines the season of fishing and the use of cattle, and their maintenance. Fishing is discussed in a separate chapter (see below).

Cows, buffaloes and goats face their most difficult time in July-September, when food and water are scarce. Usually co ws and buffaloes are not milked during this period. After they have calved, they can be milked regularly for four months, from October to May. They are milked by either male or female household members. The milk is further processed by the women.

Goats are not milked. They are kept only to produce meat, and hide for the women’s New Year drums. They are slau ghtered at home, but often by someone in the neighbourhood who is known to be a keen hunter. Cattle flesh is also eaten, though the animals are not slaughtered at home. They are sold to traders and the meat is bought, if the household can afford it. According to the villagers, wild buffalo flesh is eaten if the animals, when caught and tied, die while struggling to free themselves.

The animals graze in the dry tank bed, on harvested paddy fields (adding manure to the soil), along the roads and on the previous year’s swidden fields. The official truth is that the animals are herded, most often by boys. Yet in the village surroundings this is very seldom the case, at least not thr oughout the entire day. During the dry season, when they are not milked, they are often not even taken in for the night.

Young and weak animals are sometimes given additional food during the driest season: paddy-straw preserved from last season’s harvest, or leafy branches, or freshly cut grass ga thered by the children, day by day. In the dry season it happens (less often nowadays, according to the villagers) that a male of the household takes the herd north-east, to the unoccupied area around Gallinda, where water and grazing grounds are more abundant. The open grasslands at Gallinda might be the result of previous human activities, an assumption strengthened by the presence of tanks in the area.

Figure 16:12 Cattle-branding iron. Brands indicate ownership. Talkote village. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Food Procurement: Labour Processes and Environmental Setting

We found, as a contemporary practice, that wealthy buffalo and cattle owners in Pidurangala send their cattle to ho useholds in the remote Kosgaha-ala village, during the dry season. The recipient household is responsible for the animals and given one cow buffalo per year in return.

Today, ownership of cattle is shown by branding the an imals. The branding device is an iron rod (suruttu kolaya). The documented piece had a diameter of about 0.5cm, was 49cm long and bent into a half-circle at one end. No other special features associated with the practice could be documented. Even if similar devices were used previously and are still to be found among settlement site material, it would be difficult to identify them as branding devices.

The wet-rice environment then, does not provide for ideal grazing during the cultivation season, for the animals have to be kept away from the fields and the tank is full. Also the livestock population seems too large - at least as it is presently organized - for a paddy cultivating village to support it in the dry season.

What is obvious, however, is that animal power is much more important in wet-rice cultivation (for field preparation and threshing) than in swidden cultivation (where no animal power is utilized).11 Bullocks and buffaloes are also used for transport, as draught and pack animals.

To infer cattle keeping the osteological material is probably the most important, though the animal pen should be identifi able in case larger surfaces are opened up during excavation. In the cattle pen there will be a considerable accumulation of dung, which might be possible to trace through phosphate analyses. The enclosure, built of wooden posts, might also leave post-hole traces as indicators. A community in settled conditions, using the animals also for milk, should have had an interest in keeping the animals penned, at times.

Goats are kept in smaller enclosures. For example, in Di- gampataha village, the goats were seen occupying a hut built on a low, wooden platform raised on wooden posts. Here identification might be more difficult.

Talking of the wet-rice landscape proper, there are few species available for collection, compared to the swidden field or jungle paths. Certain stalks and seeds and mushrooms are available in and around the tanks, mainly during the wet se ason: November to January.

Concluding discussion.

To sum up, wet rice cultivation requires a certain degree of coordination and cooperation between the cultivators below a given tank. Each field has its specific owner and cultivator (which need not be the same person). Animal power is impor tant in field preparation and threshing. More animals for draught-and-trampling power, milk, meat, manure and, to some extent, their horns and hides (goat) are kept in the predominantly wet-rice cultivating village, as compared to the subsistence-swidden dominated village.

Figure 16:13 Largest cattle-pen in Talkote village, with brand-marked cattle; mid-September. Posts in background once carried a thatched roof. Previously, most of the dung

was sold to Tamils from the north. Now thrown outside

enclosure. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Additional labour has often to be hired for weeding, har vesting and threshing, tasks which are conducted in a con centrated period of time. On the very tentative data gathered in our interviews, we get an indication of a larger amount of man hours and a bigger yield area-wise in wet-rice cultivation, as compared to swidden cultivation.

Important food-procurement activities are collective fish ing in the tanks during the dry season, followed by individual wet-season fishing in tanks and streams. Fishing probably will be seen through osteological material only. Hooks and the iron blade of the kastana patiya might have been used, however, in the pre-modem situation as well (see below, under fishing).

Finally we shall observe that the combination of wet-rice cultivation with other water-related activities is not exclusive to Sri Lanka. The elaborate system of rice-fish-silk production practised in east China and south Japan for centuries, is a well known example of this.12

Chena cultivation, foraging, trapping, hunting, fishing

Swidden cultivation in our study area obviously can’t be viewed as static, either spatially, through time, or as regards crops grown, or degree of subsistence orientation. The study area also has to be related to the overall Lankan picture. The main problem is that no (published) field studies have been carried out focusing on the history of swidden cultivation.

Figure 16:14 One type of goatshed in Digampataha village. There are no walls; goats are tied in the shed.

A construction with low archaeological visibility.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Regarding the environmental setting in an islandwide pe rspective, De Rosayro states in 1949 that in Sri Lanka, in contrast to other Asian countries, flat land in dry, mixed ev ergreen forest which is not under irrigation, is preferably ch osen for swidden cultivation, instead of hilly areas of wet evergreen forests (De Rosayro 1949:51). The lack of shifting cultivation in the up-country, however, developed during the 19th century, depending on the establishment of plantations as pointed out, for example, by Michel Gelbert (Gelbert 1988:38- 39).

Regarding spatial and chronological development, we kn ow nothing of the beginning of swidden cultivation. As po inted out by R.A.L.H. Gunawardana, the first mention of dry grains on swiddens occurs in inscription material not before the 9th and 10th centuries (Gunawardana 1971:15). This, of course, reflects the interest of those who ordered the inscrip tions and is no indication of the beginning of swidden cultiva tion.

Regarding crops and location, we can discern four stages of development based on written source material and today’s changing situation.

One stage - which we don’t have to think of as the first - testified to inscriptions regarding taxation, which mentioned sugar cane, sesame and cotton as important swidden field crops, each the base of important cottage industries. We don’t have to think of them as the only crops grown on the swidden field. What the inscriptions tell us is only what crops were interesting from the taxation point of view.

Then there is the possible expansion of swidden cultiva tion after the decline of the dry-zone civilization, as indicated by the Sinhala and Tamil swidden place-names analyzed by Michel Gelbert. The new swiddens were taken up in the wet zone, up-country, in areas of Anuradhapura, Madavacciya, Vavuniya, Padaviya, the Colombo-Puttalama-Kurunagala ‘C- oconut Triangle’, in areas from Trincomalee to Tirrukkovil and in the Pottuvila and Kataragama areas. According to this study, the establishment of swidden place-names should have started not before the 14th century and ended not later than the 18th, or early 19th century (Gelbert 1988:38-39).

An important question: is this only a picture of expanding subsistence-swidden cultivation, or were the clearings also a means to open up the wet zone for economic expansion?

Then we have the situation of yesterday and partly of today, of subsistence oriented swidden cultivation characte rized by household labour and consumption, combined with various additional food procurement activities.

In the 17th century, Robert Knox mentions some of the dry grains on swidden land that we found during our field survey, and he describes cultivation practices that are very similar to what we find today.

Michel Gelbert calculates from studies of aerial photog raphs that the swidden cultivators of today, producing solely for their own consumption, constitute no more than 2% of all swidden cultivators in Sri Lanka (Gelbert 1988:137).

And finally today there is an increasing amount of cash crops grown on the swidden field. As in the case of wet-rice cultivation, subsistence-swidden cultivation is fast changing. More of the cultivator’s crops are grown for sale, and the traditional dry grains, such as kurakkan, are pushed back in favour of cash crops like tobacco and vegetables. In some cases the peasants in our study area declared that they have stopped growing kurakkan and similar grains altogether.

This trend towards cash-cropping is not specific to our few studied villages. In 1983 the Department of Census and Statis tics pointed out in a report that swidden cultivation had ex panded throughout the Dry Zone, and swidden cultivators produced a growing amount of cash crops.13 Also, forest pr oducts in our study area, like honey, are now largely sold instead of being stored and consumed by the household.

Land use and labour process in the study area

An outline of the seasonal planning and associated ac tivities of subsistence-swidden cultivation will now be given, based on nine interviewed households, documentation of eq uipment and field-walking. However, the changing situation and the fact that the traditional, subsistence oriented swidden field also contained some cash-crops, as for example aba (mustard) must be kept in mind.

The Maha season is the most important swidden season. One less important swidden season coincides with the Yala season in May-June. The sites of the Maha swidden field are selected in June-July. When asked what physical factors deter mined the given farmer’s selection of land for swidden cultiva tion, the answer was: depending on what was to be grown in the chena. Regarding dry grain such as kurakkan, our inform ants stated that dense jungle on a small hill was the best location. Flat lowland where water could collect during the rainy season was not desirable. The place should have lain fallow for at least five to eight years. A ten-year fallow is even better, but nowadays almost impossible to find.

Michel Gelbert discusses the selection of chena land based on interviews carried out in three regions of Sri Lanka. We found that our informants looked in the first place for a su itable topographical setting, with the hydrological implications in focus. For Gelbert’s northernmost study area, which is north-west of our own, we find however that quality of soil and type of vegetation were the most important criteria for selection of a chena site (Gelbert 1988:80-83). The soil quality could, of course, also depend on the topographical setting.

Often the new swidden site is selected while the male cultivator is doing other things in the jungle, like hunting with gun and dogs, or collecting honey.

In our study area we found examples both of smaller swid den fields, cleared and cultivated by an individual household, and larger swiddens cleared by males from neighbouring households, or relatives, and subsequently divided into in dividual plots.

Clearing starts in mid-July and the cut vegetation is then left to dry for about one month and fired for the first time around mid-August, by male household members (one or two from each household). Larger trees are left standing. After burning they generate fresh buds and leaves. From some sp ecies of trees these are plucked to be used as food, or as a beverage.

Two or three days after the first firing, women (one or two from each household) pile up what was not burned at first and set fire to it. The fence is constructed during the first week of September, by male and female household members together. Each household is responsible for the fence bordering that part of the swidden field used by it. For clearing, the big, long- shafted billhook (loku katta) and the smaller, long-shafted bill hook (katta) are used. For fence construction, the hoe is used for digging and the axe and katta for cutting. Several techni ques are used in fence and hedge construction. If binding is necessary,‘wickers are used.

Sowing and planting takes place from the first rains in mid-or-end October - or, in case swidden is combined with wet-rice cultivation, during the second week of November (after wet-field preparation is completed). Sometimes relatives exchange labour for sowing and planting. The top soil of the area to be sown/planted is loosened by a hoe. Males and females work together: men mainly hoeing, women mainly sowing.

Figure 16:15 Chena field divided between different cultivators; seven types of seeds are simultaneosly broadcast.

Diyakapilla village, late October. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

tinues until horse gram is harvested at the end of March. Panicum millet is cut low, in bunches, with the ordinary sickle, as is swidden rice (which is grown in separate fields in other topographical settings) at the end of February, or early March. The other dry grains are cut ear by ear with a small sickle (kurakkan katta). Finger millet (kurakkan) is cut in mid February, sorghum (idal iringu) in late February or early March. Traditionally, a bowl-shaped basket (kude) made of kirival was used to carry the harvested ears. The one docu mented was made by the householder’s old father. A bigger variant was used in the kurakkan harvest that was studied.

Harvesting with the kurakkan katta is women’s work. It is carried out by household members, sometimes with the help of near relatives who will, in turn, get help to harvest their own fields. Carrying the harvested produce from the swidden (sometimes after drying) is, in theory, male work. Usually only one harvest is taken from the swidden field. The fields are not weeded.

Robert Knox witnessed the dry land cultivation of the 17th century. He mentions "Coracan’, "Tanna", "Moung", "Omb", "Minere", "Boumas" and "Tolla" growing on dry land (Knox 1981:112-113). The ear-by-ear cutting of certain grains by women harvesters was noticed by Knox: "The way of gather ing it (tana) when ripe, is that the Women (whose office it is) go and crop off the ears with their hands, and bring them home in a basket. They only take off the ears of Coracana also, but they being tough, are cut off with knives." (Knox 1981:112).

Figure 16:16 Ear-by-ear harvesting of kurakkan.

A1 1 /2 acre chenafield of mixed cropping. Ilukvava village close to Gallinda Mahavava, late February. Harvested ears are placed in a basket kept beside the harvester. Photo: Eva

Myrdal-Runebjer.

Davy says from his early 19th century horizon: "...reaping, or, when the straws are not saved, of gathering the heads of corn." (Davy 1983 (1821):201).

Regarding the dispersed harvesting of swidden fields in the mid-19th century, Samuel Baker says: "Thus may be seen in a field of korrakan (a small grain), extensive coracana, Indian com, millet, and pumpkins, all growing together, and har vested as they respectively become ripe." (Baker 1983 (18- 55):35).

Henry Parker describes both the implement and the cutting technique used at the end of the 19th century. He also notes women to be the harvesters in swidden cultivation: "The Si ckle, Dae-Kaetta, has two forms, a long-bladed one... and a diminutive one of similar shape which is only used for cutting off the heads of millet and other grains grown in the temporary clearings called Hena, or by Tamils Chena, this reaping being

Figure 16:17 Basketful of kurakkan ears is carried to the field hut and emptied. It took 20 minutes for the harvester to

fill the basket, which contained approximately 2kg of kurakkan ears. Ilukvava village, late February.

Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

invariably performed among the Kandyans by the women alone." (Parker 1984 (1909):554)

The ear-by-ear harvest makes it possible to make use of every single ear. During the kurakkan harvest we saw the women taking care to cut even the straw that had been tr ampled down.

The dispersed harvesting season is noticed by Michel Gel- bert in the 1980’s. He states that harvesting is either done day by day, according to the needs of the family, or at one time. That this has implications for mobilization of labour is further noticed: "Grain has the disadvantage that if it is planted or sown simultaneously, the entire crop will mature and has to be harvested at the same time, thus requiring a big labour input within a short period." He further describes three harvesting techniques: hand-plucking of grain heads, hand-knife cutting of grain heads and sickle-cutting of stalks, observing all three techniques to be used for grains on swiddens in his three study areas. Tubers and roots, on the other hand, are dug out by crowbars, or sticks and hoes, if the soil is hard. Vegetables are cut, fruits and pulses are plucked (Gelbert 1988:159). This was stated to be the case in our study area as well.

The swidden grains which are cut ear-by-ear are stored intact in an airy ‘storehouse’ built of palm leaves, on a wooden floor raised on wooden posts (atuva). They are threshed, ‘me al-wise’, in a wooden mortar (vamgediya) by the women of the household and ground on a rotary quern of stone (kurakkan gala).

Vegetables are consumed directly after harvest, as are tu bers which are left in the ground until needed. Spices are dried and stored, if not sold.

After the harvest, cows, buffaloes or goats are allowed to graze in the field. Compared to the wet-rice village, less open ground is usually available in the swidden village for animals to graze upon in the dry season.

Fishing is carried out by men of the household, as in the mainly wet-rice village.

On their way to the swidden field, or in the swidden itself, the women find a variety of wild edible roots, stalks, leaves, berries and fruits. Our informants stated that several wild plants will preferably grow in the chena field. Siriweera men tions at least one of these (tibbatu) as cultivated in the swidden field today and in ancient times.14 This might be an example of different levels of intensification in swidden cultivation, in different periods and areas.

Approximately 70 different wild species, including four species of mushrooms that used to be gathered, were men tioned by our informants. Their local names were given in each case. However, several still remain to be botanically iden tified. They are collected for food, for making beverages and for medical purposes. Most of them are consumed on the spot (as berries) or within one or two days. Apart from those used for beverages or medical purposes, only a few species (‘vegetables’) are cut and dried and stored for about six or eight months. While men also pluck berries and fruits, the planned and everyday gathering is done by women.

Figure 16:18 Discussing wild plants with an elderly woman from Ilukvava village. With increased cash-crop cultivation it

is now mainly the older people who have knowledge of different wild plants, roots, fruits and mushrooms that can be

used for food. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

Another jungle related activity is collecting honey. The most important season is from May to September, which is the dry season. Beehives are found high up in trees and in cave sites in remote forest areas. Often three to four men (relatives or neighbours) go out together. They leave in the morning and come back before sunset. Trees are climbed with the aid of a foot-rope. Parker, quoting Nevill, mentions frail ladders made of cane being used in the late 19th century, to descend steep rocks, to reach the hives (Parker 1984 (1909):71). This was not mentioned by our informants.

Clearing and cutting tools made of iron, such as axe blades, clearing knives with broad blades (vak pihiya), billhooks (katta) and small knives (ul pihiya, kopi pihiya) were used to hack branches and cut the honeycombs. For the latter purpose, whittled wooden sticks were also used. Earthen pots were used for long-term storage. All the other materials for honey collec tion are perishable: the big leaves folded around the honeycombs for transporting to the village, the coconut husk ‘sieve’ and the labu kataya (the hollow, dried bottle gourd) to keep the honey. Previously, honey was collected mainly for household consumption, but it is now collected mostly for sale, and the plastic sheets and glass bottles have made their entrance.There is no equipment of non-perishable material that is specific to honey collection. It could be investigated however whether honey could be traced chemically from storage jars.

Swidden land from an archaeological perspective.

What is interesting as regards dry zone cultivation is that, to my knowledge, we do not find ploughed dry land sown with dry grains-as seen, for example, in the interior of Tamil Nadu. Panabokke suggests this is determined by the texture of the soil, which according to him makes dry land plough agricul ture next to impossible in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka (Panabokke, personal communication, October 1990).

In Talkote however, we found that rice was sometimes sown on swidden fields in flat lowland, where water could collect. We were told that flat land minimized erosion. Flat fields were often turned into a kind of permanent ‘dry land field’ for paddy, enclosed by the usual paddy field bunds (see above, under wet-rice cultivation). The fields were manured by letting the cattle graze after harvesting.

Paddy fields not linked to any tank were seen on flat land below small hills, during the field survey in the Kiri Oya valley, in 1988. Fields such as these can be ploughed after the rains have started, as in Tamil Nadu, but their water-logged state during the rainy season would probably rule out the growing of dry grains like kurakkan. The question whether dry grains found in archaeological material indicate swidden cul tivation on unploughed fields, needs further investigation.

In a field survey situation however, we will find it difficult to determine a given settlement’s potential chena land, as swidden cultivation in this environment is very flexible re garding topographical requirements; and the distance from the homestead varies, depending on the availability of land and utilization of the surrounding land for other purposes.

During our field survey we found most swidden fields to lie within 30-45 minutes’ walk from the village. Male ho usehold members lived on the chena to protect it from wild animals, not because it lay too far off. The rest of the family stayed in the village. This situation corresponds to what Gel- bert found in his northern study area (Gelbert 1988:90-93). This however is dependent on the overall land use situation, and we can’t count upon it as a static model for our study area.

Is there, then, any possibility of detecting and dating pre modem chena cultivation apart from the indications found in the settlement site material?

Any once inhabited area which is not covered by primary forest could have been used as swidden land. To test if datable layers of charcoal from swidden cultivation could be found, a small test-pit was dug in 1990.

The test-pit was dug in traditional swidden land, within the traditional boundary of Ilukvava village. The area had been fired three years back and was now covered by bushes and small trees. We selected swidden land with a flat topography, so that not much erosion or deposits of soil would have af fected the soil profile.

Figure 16:19 Test pit in fallow, flat chena field, in an area where swidden cultivation is traditionally conducted - to test

archaeological visibility of chena cultivation. Ilukvava village, late August. Photo: Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

After digging 0.53m we still found the usual red-brown earth profile, but no layers of charcoal. Small particles of charcoal however, were seen dispersed in the soil all the way down.

The conclusion was that where no soil deposits have taken place, the vegetational cover and the swidden technique (leav ing larger trees standing) don’t supply enough material to form a layer of charcoal, in the Lankan context. Unlike temperate regions such as Sweden, where the abandoned swidden is overgrown with a thick vegetational layer, the surface of dry zone swidden will remain exposed to forces of wind and water, dispersing the charcoal fragments that have formed. That the charcoal particles were dispersed throughout the pr ofile was tentatively interpreted as caused by biological forces (worms and roots). The technique of loosening the upper sur face with the hoe could also play a part, although it doesn’t explain the downward drift of the charcoal.

Tank sediment was also suggested material for tracing the history of swidden cultivation on a larger scale. The idea was that erosion from the catchment area of a tank would form sedimentation layers in the tank, making it possible to identify and date distinct soot and charcoal layers which have formed.

The study of tank sediment was taken up in 1991 and we found clearly distinguishable layers formed, some containing charcoal. The impression so far, however, is that this results from settlement activities above the tank.Cooperation with soil scientists of various disciplines is urgently needed to pursue this field of research. The selection of suitable test pit sites for sedimentation studies has to be further discussed: for instance, flat land below a hillock, where erosion deposits its layers above the swidden surface.

Another possibility would be to study sedimentation layers in abandoned irrigation canals, for the presence of charcoal and catchment area vegetation residue, in the form of macro fossils, pollen and phytoliths. This will be discussed in future irrigation studies.

Studies such as these would add information regarding the relative importance of swidden cultivation during the wet-rice based civilization and after its decline.15

Turning to what would indicate swidden cultivation on a settlement site, we have already mentioned the macro-fossils that might be found. Given poor preservation conditions, we should also consider using the indications provided by ar tefacts. Hoes, axes and bill-hooks are used also in wet-rice cultivation. Regarding harvesting implements however, we have found a specific implement, the kurakkan katta, which is used in the ear-by-ear harvesting of dry grains only.