New Information on Mapagala

- ADMIN

- Aug 15, 2021

- 35 min read

W.A. KUMARADASA

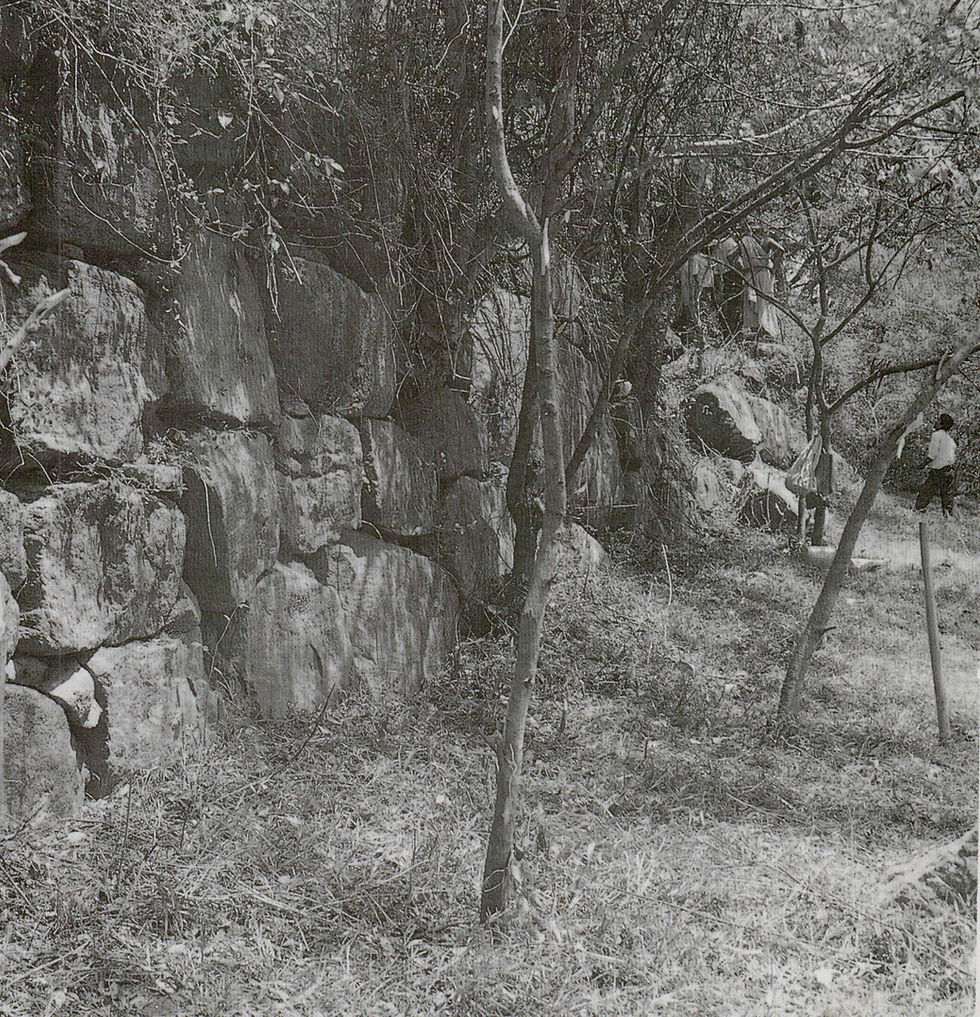

Figure 9:1 Great retaining wall around Mapagala on the western side of the rock. Seen from the north.

Photo: Mats Mogren

INTRODUCTION

About 400 metres south of the Sigiriya rock are two medium sized hillocks, covering an extent of about 17 acres, which today are known as ’’Mapagala”. The site covers 250,000m2, inclusive of adjacent areas around the rocks. It is delineated by the Sigiriya complex on the north, the Sigiri Mahavava on the east, Petangala, the rest house and Kayamvala village on the west and the Sigiriya Oya on the south.The twin rocks which are called Mapagala North and So uth, are about 11 acres and 5 acres in extent respectively. The North rock differs from the South rock in that its summit abounds with natural boulders, whereas the South rock is devoid of such boulders. The surface of the northern summit is a flat area where brickbats and fragments of a small, dil apidated stone wall are visible. There is also a natural pond with a gradient from north to south. No other structures are visible today (Bell 1908, mentions the remains of a brick structure), but potsherds, brickbats and pieces of tiles are fo und. Pieces of quartz are found in plenty in the soil layers upon the summit. Potsherds (Black-and-Red Ware), small quantities of iron slag and rare flakes of chert are also to be seen.

On the South rock, which is covered with thorny jungle, there are large quantities of brickbats. The ruin of a structure of unidentified function has some bricks still in situ and the remains of a dilapidated retaining wall are also to be seen. There are signs of a bridge-like road spanning the pass con necting the two rocks (Bell 1908). This road had been con structed with two lines of stones arranged on either side of an existing stone slab. Traces of retaining walls, which have been subject to erosion, may have been used as flights of steps leading towards the west. Although clear signs of such a flight of steps leading east are not visible, traces of a path are discer nable.

Traces of some sort of constructions are to be found tow ards the east of the North rock, the west of the South rock, and among the boulders. Some steps subjected to erosion, which can be considered the ancient access road to the North rock, are found opposite the southern face of the Sigiriya rock.

There are six small, natural caves in the rocks. Bell refers only to one cave on the eastern front. Although dripledges have been made in some caves, they look very rough com pared to those in Sigiriya. No inscriptions are found. Potsherds, brickbats and other cultural finds are visible. Fragments of Black-and-Red Ware bowls were found in some of the caves. In cave No. 2 there were remains of a wall, built of small pieces of stone, plastered with clay mortar. It seems these caves had been used on several occasions.

The construction that makes Mapagala unique is the ter race wall built around its base. For the main wall, which is up to 4m high and about 2m wide, undressed stones of a size about 2.5x2.5m have been used. The construction, made by connecting natural boulders, has added strength to the wall (Chandralatha unpubl.). The stone blocks used in the construc tion of this wall are much larger than those used in the walls of Sigiriya.

Even though the wall may look primitive, having been built of undressed stone blocks, it is undisputable evidence that the builders of the walls at Mapagala had been masters of an advanced technology; and controlled a mass labour force.

Theie is a second, lower wall running parallel to the main wall, on the west of the North rock. Bell (1908) says this may have been either a street, or a path. In the same area, in the vicinity of the Archaeological Department’s circuit bungalow, there are several lines of stones which seem to have belonged to yet another small wall.

West of the Mapagala rocks is a smaller rock, with bou lders running north-south. South and south-west of this rock formation is an iron production site (SO. 66). To the north west of this small rock is a rock called Petangala. Ruins of a stone foundation are found on its summit. Unlike the Sigiriya gardens, it is very rarely that cut marks for post holes or brick constructions are seen on the rocks of the Mapagala complex.

The tank bund of the Sigiri Mahavava runs from the sou thern end of the foot of Sigiriya rock up to Mapagala, and from the southern end of Mapagala up to the Kandalama mountain range and further (see new data in Myrdal: "The Archaeology of Irrigated Agriculture" this volume). The present Sigiriya village is situated on a section of the ancient tank floor. The tank as it is today, situated north-east of Mapagala, merely looks like a large pond, but the ruined tank bund indicates that the Mahavava had once been a macro-scale tank (Blakesley 1876; Bell 1906-1908). The bund between Sigiriya rock and Mapagala has had a roadway upon its crest. There are signs of repairs effected to it from time to time (De Silva, R. 1967/68, 1968/69).

THE HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

Chronicles

Historical sources regarding the history of Mapagala are rare. However, judging from the ruins and artefacts found, it is clear that this site is a place where human activity has taken place during various periods of time. It is not unreasonable to consider Mapagala, Sigiriya and Pidurangala as a single ar chaeological complex. These rocks can neither be separated from one another in the research process, nor can they be considered in isolation. Thus Mapagala is part of the history of Sigiriya.

From various sources it is evident that royal patronage was afforded to this area in the Early Historical period (Ranawella 1984; Seneviratne, A. 1983:65-66; Ilangasinghe 1987:7-8). The region had witnessed important state activities since the earliest Anuradhapura period, when the Ritigala fortress con tributed to the siege of Upatissagama by King Pandukabhaya. According to Geiger, places like Giri Laka, Kasa Pabbatha, Thulaththa Vapi, which are connected to the battle between Dutugamunu and Elara, must have been situated in an area between Sigiriya and Minneriya (Mahavamsa, commentary by Geiger 1950: 200-291).

The area also formed an important link in the ancient road system connecting Rajarata with Malaya (see for example Wimalaratne 1984:19). These roads became more important during the Sigiriya Kingdom in the 5th century, in matters of transport and external relations (Wimalaratne 1984). Historical sources reveal constant movement of forces towards the inte rior of the country and that there existed a communication network among the population for defence purposes.

Inscriptions

A large number of inscriptions have been found from Sigiriya and the surrounding areas. (Ranawella 1984; Somadeva this volume). This collection of inscriptions, which is a positive indication of the existence of ancient monasteries, makes it pos sible to generalize on the extent of settlements and development of population during the period, since the patronage of a self-suf ficient people is necessary to support a large monastery com plex.

Some of the Early Brahmi inscriptions mention the title parumaka. Although information of elite social groups who were given this title is sparse, the extension of that class and their activities show that they were a privileged class in so ciety. This was a traditional title which could be used for both males and the females alike, meaning a ‘leader’, ‘head’, or ‘a senior person’ (LiyanagamageT965:194). A social system of aristocracy, based on lineage, or a group of people in the ruling class who held important positions in society, is envisaged by this title. Village leaders who enjoyed some power in their respective villages, high officials who held titles of senpathi, badagarika etc. and property owners can also be considered to have belonged to this group.

Paranavitana is of the view that they were the group of people who assisted the king in governance of the country and implementation of economic activities of the land (Parana vitana 1970). Indrapala contends that the word parumaka is a derivation from the Tamil word parumakan, and that they may be regional leaders who were descendants of Dravidians (In drapala 1965:306).

According to Ilangasingha, the existence of such a large number of parumakayo among those who offered caves in settlements around Dambulla, is strong evidence of the fact that the term parumaka was used to identify only the elite class and not a designation, as was the case during the Kandyan period, when the term nilame was a title used collectively for the elite class. (Ilangasinghe 1987). Apart from religious ac tivities, the parumakayo were engaged in tank building (To- nigala inscription), trade (Paranavitana 1970), teaching, etc. At times they were so powerful as even to be in a position to interfere in the state machinery.

The above-mentioned inscriptions give evidence that there were parumakayo in possession of the area in and around Sigiriya. Although no clear information is available regarding their homes, references such as ‘parumaka naguliya lena9, ‘parumaka abijiya lena\ etc. may refer to the caves which served as their homes. Those caves were subsequently con verted into monasteries by their owners. However, if any con structions had been made, they may have been either destroyed or changed owing to later settlements; or else suffi cient evidence does not remain whereby they can be identified.

There are several inscriptions too, found in this area, which are categorized as Late Brahmi inscriptions (l-5th centuries AD). Inscriptions belonging to the reigns of several kings who ruled during the period from the 5th - 10th centuries have been found (Ranawella 1984; Godakumbura 1964/1965; Tissa Kumara 1990). The common feature of all these inscriptions is that the references are to donations made to monasteries and patronage. However, it is this collection of inscriptions which is the strongest and most authentic evidence of the existence of settlements in this area since protohistoric times.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH

Although more than a century has passed since research in Mapagala was first taken up, actual archaeological fieldwork so far has been very limited. Most has been done at survey level and no further. In 1876 Blakesley evinced some interest in conducting a survey on this site. Emerson Tennent’s Re ports provided him with the necessary sources. He strongly believed in earlier historic constructions relating to Sigiriya and Mapagala.

He further says that if the wall around Mapagala was meant for the protection of the site, Sigiriya would have of fered better protection in view of its location. About the wall on the east, he is of the opinion that such a wall on that side is unnecessary, in view of the fact that it is protected by water, the Sigiriya Mahavava having been built later. Elaborating his point, he says that although the necessity of water was felt for moats.and gardens etc., during the Kasyapan period, there was no necessity for the construction of a large tank, and it was during the time of King Parakramabahu (1164 AD -1197 AD) that such large tanks were built for agricultural purposes. He explains that owing to the very nature of their construction, the dams fell into disrepair on several occasions. Thus it was necessary to build large tanks to facilitate agriculture.

Besides the above contention of Blakesley, his other views are rational and reliable. The historical details put forward by him do not seem to be relevant, in the light of our sources, in the context of Sigiriya or Mapagala. However, he is of the view that the original constructions at Mapagala date back to the pre-Kasyapan era, in the Early Historic period.

The second scholar who did surveys on Mapagala was J.B. Andrews (1909). Drawing attention to the uniqueness of the wall at the base of the rock, he expresses the view that it may be a structure belonging to the megalithic period. He says this stone wall may belong to the Vijay a Rama period, or even to an earlier period before the structures in Anuradhapura were built. Further, while pointing out that stone walls of such magnitude, belonging to the early phase of the Roman civ ilization, are to be found at several places in southern Europe, he cites the example of stone walls near Pyu Ricard in Mo naco, referred to as ‘Ligurian’ (Andrews 1909). Although Andrew’s dating is too early, the rationality of his argument can be accepted. He contends that the constructions at Ma pagala may date back to the pre-5th century AD. When the finds of quartz, Black-and-Red Ware, iron slag, chert, etc. on the summit of the rocks are considered, it is not difficult to agree with him. However there is not sufficient evidence to agree with his megalithic dating.

H.C.P. Bell, who paid attention to the study of Mapagala, reiterates that the history of Mapagala could not date beyond the 5th century AD at all, and emphasizes that it is not prehis toric. He stresses that the residence of the Mahadipada or Mapa of King Kasyapa, who built Sigiriya, may have been built there. He is of the view that the vast wall resembles the large wall of the Incas at Sacsahuman, in South America (Bell

1908). There is no reason to build the walls at Mapagala stronger than at Sigiriya, which was more important during the Kasyapan period.

Among hypotheses built on the basis of the architecture of Mapagala, predominant are that this was a fortification (La wrie 1898; Deraniyagala, P.E.P. 1973:10; De Silva, R. 1974; Bandaranayake 1984; 1990), a monastery (Blakesley 1876), and a palace or a residence of the elite, (Bell 1906; 1907;

1908).

According to the above-mentioned research, views on the dating of Mapagala can be divided into three main groups: I. A creation of the prehistoric period. II. A creation of the protohistoric period. III. A creation of the historical period. When the available data is considered, it becomes clear that features of all these periods mentioned above are to be found at various levels. However, no in-depth research has been done with a view to identifying these factors separately.

Adikari (this volume) has identified prehistoric camp sites, not only in caves like Aligala (Sigiriya), Pidurangala, Dambul- la and Potana, but also in open places like Millagala and Tammannagala. He maintains that Mapagala may also have been an open area hunting ground, since there are stone imple ments among the collection of quartz debris found at this site. Also, the existence of a pond, or water hole, on the flat sum mit, strengthens this possibility (Adikari this volume). A stage of inter-relationship or interdependence between the mega lithic and Brahmi periods, or a stage of transition, has been revealed through studies in areas like Ibbankatuva, Dambulla and Pidurangala (Bandaranayake 1990:22-23). Particulars of the resources utilized by societies during prehistoric and pr- otohistoric periods in the Sigiriya and Habarana areas have been confirmed. (Seneviratne, S. 1990).

Interpretations of the name Mapagala

How and why this place was called Mapagala cannot be established with certainty. It may be a corrupt form of another word in use for generations. The name Mapagala is not men tioned in written historical sources, but by the time foreign travellers like Bell, Blakesley and Andrews started visiting the area, these two hillocks were known as ‘Mapagla’. Various interpretations are given to the genesis of this name.

It has been established by Blakesley that the maha paya of King Kutakanna Tissa, and other constructions, are among some of the ruins found near Mapagala. Blakesley is of the view that ‘Mapagala’ was derived from the words ‘Maha- pay a-gala’ or the ‘Great Precipice Rock’. (Blakesley 1876). The precipitous drop on the west and the south of these two rocks lends evidence to this conclusion. But when one thinks of Sigiriya, which has a steeper slope, one begins to wonder why a small rock like Mapagala was thus named by the people in ancient times. This has to be further examined.

The "gala" or rock where the viceroy (Mahadipada or Mapa) resided, may have been called Mapagala. Bell (1886) emphasises that the palace of the viceroy may have been built on this rock by the time Sigiriya became the seat of the kin gdom (477-495 AD) and so later came to be known as Ma pagala. Although the term adipada, or apa (viceroy) is an equivalent of ‘heir to the throne’, very often all royal princes were known as adipada, or viceroys. This designation is first mentioned during the reign of King Silakala in the 6th century.

The term Mahadipada - Mahapa - was a ceremonial title conferred on the ‘heir to the throne’. In chronicles these titles are mentioned during the time of King Dathopatissa (650 AD) (Geiger 1969; Liyanagamage 1965). King Dhatusena appo inted his nephew (Migara Senevi) as his commander-in-chief. Migara served King Kasyapa too, in the same capacity. There fore it can be considered that King Kasyapa had a viceroy, or mahadipada, in keeping with the tradition of the historical line of kings. It can be surmised that subsequently he was known as 'mahadipada' in folklore. The name of the residence of this mahadipada may have lent itself to the place under survey.

A structure found near the Basavakkulama tank, in Anur- adhapura, has been identified as a mapa palace. This is considered the best example of a building of the Lankan elite class (Godakumbura 1976). The structural features on the summit of Mapagala, identified by Bell, closely resemble a large st ructure, with cells, passages and verandahs, of a summer pa lace upon the summit in the ancient city of Sigiriya. (Bell calls them islands: Bell 1908).

A large number of ‘attam inscriptions, which contain in formation regarding the privileges and benefits enjoyed by mapas during the later centuries of the Anuradhapura period, have been found in surrounding areas. They are at Vayaulpota (Sena KK, 853-887 AD); Mihindal Mahapa, Ramakale-Ma- pagala (Kasyapa IV, 898-914 AD); Kasabal Mahapa, Pid urangala (Dappula IV, 924-935 AD); Uda Mahapa (Ranawella 1984, 203-209). Thus the word Mapagala may have come into use after the titles of viceroy, or mapa.

The fact that written evidence which contains the names of these titles found in abundance in this location, leaves room to surmise that this area may have served as a centre of ad ministration, controlled by holders of the title mapa. It can also be considered that subsequently this name found its way into common parlance in the belief that the ‘attam' pillars in Mapagala are those of the mapa belonging to the period of King Kasyapa.

THE SARCP WORK

Within the framework of SARCP, fieldwork on Mapagala was commenced in 1989, when test excavations on the sum mit of Mapagala were carried out. This was followed by the excavation in 1990 of a trench transecting the main wall, at the foot of the western slope.

Questions, hypotheses and objectives

Mapagala can be presupposed to be one of the best places in the region, next to the Sigiriya complex itself, for a study of administrative and socio-economic circumstances in ancient times. At the outset of the investigation, several major ques tions regarding Mapagala were taken into consideration. Wh en were the terrace walls constructed? What was their function? Was the site occupied continuously, or was it aban doned at one time? If so, why?

The fact that the construction of Sigiriya and Mapagala cannot be considered on an equal footing renders it impossible to apply the archaeological theories developed about Sigiriya in the context of Mapagala.

Since there is evidence which reveals that settlements had been in existence in the Sigiriya region prior to the construc tion of the citadel, there is a possibility that Mapagala too, dates back to pre-5th century AD, as presupposed by earlier researchers. So far we do not have a clear idea of what purpose was served by Mapagala, with its enormous embankments; whether it served as a regional administrative centre, or the residence of local leaders, or whether it was a religious centre.

The existence of quartz in abundance around the area also leads to another experimental approach. Does the presence of quartz have any connection with the activities of those people who built this wall and other constructions? Or does it have any connection with previous, or subsequent, activities? Is it waste from the production of microlithic tools on the site; or were these fragments mixed with soil brought from outside, as fill? Is the quartz debris deriving from some other kind of activity during later periods?

The finds of iron slag in considerable quantity from the site and the abundance of iron slag on the west of this rock (SO. 66), gives further significance to the necessity of an ar chaeological study of this site. Could this slag be connected with the large-scale constructions?

Besides the large outer wall, no other traditional com ponents of a fortress are found here. Even though, at first thought, the utility of the large wall may have been to ensure safety from external forces, it may also have served as a social marker. Anyhow, with the enormous labour input evident, it is certainly not to be considered a temporary structure.

The fact that an ‘attanf inscription is found in the vicinity of this site allows the theory that the complex was connected with the ‘Mahanaga Rock Monastery Complex’, subsequent to the original phase of construction (10th century). This be comes further evident as subsequent monastery settlements too, are found in the caves nearby.

Although it can be thought that this may have been in use as a palace, or residence of the elite in the 5th century, it has been hypothesized that its period of origin lies further back. Considerable attention was paid to the protohistoric and Early Historic elite class called ‘parumakas’ (chieftains). Early Br- ahmi inscriptions mentioning parumakas are found at four different sites in the region: Pidurangala, Potana, Dambulla and Kandalama.

Thus a hypothesis was formed that the site Mapagala mi ght represent a multi-period history of occupation, with func tions changing over time: a) the site could possibly have attracted settlement previous to the construction of the terrace walls; b) the terrace wall constructions could antedate the Kasyapan establishment at Sigiriya and may represent an ear lier societal development, e.g. the central place of zparumaka, c) the site could have been used after Kasyapa’s reign (hence the name indicating a viceroy); and d) late post-Kasyapan occupation could hve ben of a monastic nature.

Excavation sites were selected on the summit and near the wall, with a view to establishing a local stratigraphy and col lecting artefacts for interpretation of the dating and function of the site.

Mapping

Although mapping of the rocks was conducted earlier by H.C.P. Bell in 1907, it was necessary to carry out a new mapping of the site. The survey unit of SARCP surveyed not only the rocks themselves, but extensive areas around the foot of the rocks as well. Detailed plotting of the test pits and the excavation trench was also an objective of this survey (fig. 9:3).

TEST EXCAVATIONS OF 1989

Two test pits, 2x2m, were dug on the summit of the North rock of Mapagala. The contextual relationship between the quartz (prehistoric implements?) and other cultural finds dis covered here, and the utility of the summit for a settlement were taken into consideration in selecting the location of the excavation. An area at the lowest point was selected for test pit no. 1, in view of the fact that the surface of the rock had a southern slope and that the shape of a pond was discernible at this place. The inference that the surface collection found near the location may have been remains which were washed down into this lower point, was the reason for selecting this location. This section, which is completely silted up now, is covered with iluk and mana. The surface layers consist of very fine sand and no cultural remains were found there. The surface elevation of this excavation site is 237.34m above sea level.

The second test pit was dug in the north-eastern sector, which was the highest point on that front. A few pieces of stone, probably parts of a small stone wall, were found about one meter east of that point. Grass had grown very luxuriantly on this site. Throughout the site quartz, a small quantity of brickbats and pottery were found.

Methods

The Harris’ matrix system was adopted (Harris 1979). Ar bitrary sub-strata were designated when necessary. These were reported under the same context number, e.g. context 1, level 1.

Each stratum was sieved using a 5x5mm sieve and sea level was reported at every 10th cm. Every stage, from com mencement onwards, was photographed in black and white and colour; and slides were made. The excavation was carried out using small pickaxes, trowels, hand shovels and hand brushes.

Results

The occurrence of artefacts relevant to our objective was very low at test pit no. 1. Both layers (see fig. 9:4) can be described as alluvial, non-cultural layers. At the end of the excavation there was no possibility of arriving at any conclusion on the basis of surface collections. Therefore test pit no.l did not yield any results.

Test pit no. 2 was very rewarding (see fig. 9:5). Excava tions were carried out on the hypothesis that the microlithic implements spread around the surface of the layer had em erged as a result of the erosion of the uppermost soil layers.

The soil strata were divided into three contexts. Quartz and stone implements, which are to be seen even on the surface, were found in large quantities in the third context, where they were mixed with Black-and-Red Ware.

The findings can be summed up thus:

1. Microlithic imple ments belonging to a stone age technology.

2. Black-and-Red Ware pottery belonging to the protohistoric period.

3. The existence of Black-and-Red Ware in the last context alone is not a coincidence.

4. Features of a common economic system brought about by the mixture of implements belonging to two cultures.

5. Environmental factors in a mixed culture. The existence of microlithic implements belonging to a mesolithic culture, from the surface right down to the bottom, has given rise to some complicated conclusions. Finds of Black-and-Red Ware pottery in the bottom layer compound the issue. Similar relationships were found in excavations of settlements in Pomparippu and Anuradhapura, and there are instances of the mixing of both these economic systems (De- raniyagala, S. 1972; Begley 1981). It is also not easy to build up interpretations based on megalithic implements alone, al though they are found extensively. A people with a knowledge of using pottery can lay claim to an agricultural economic system and a system of minor trades, based on small village units with a household economy (Seneviratne, S. 1984).

The occurrence of Black-and-Red Ware from the third context alone is not a coincidence. Although microlithic im plements are found spread almost everywhere, there is no Black-and-Red Ware pottery. Since this type of pottery was discovered very close to the bedrock, about one meter below the surface, it can be considered an undisturbed deposit.

If this is the first instance where Black-and-Red Ware pottery was found at a point very close to Sigiriya, it may be an important incident. It is also interesting in the light of Andrew’s theory on megalithic settlements in Sigiriya and the surrounding area (Andrews 1909)

In view of the above factors, it is possible to elaborate on the hypothesis:

1. That the lack of historic artefacts and occurrence of microlithic implements from the surface itself, makes it pos sible that historic strata have been destroyed.

2. That the remains of brickbats and tiles mark the last stage of the historic strata.

3. That the remaining strata relate to the prehistoric period.

4. That in view of the fact that Black-and-Red Ware were found in the last context, there is a possibility of the existence of a megalithic (cultural) settlement with microlithic usages.

5. That according to the natural location of the summit of the rock, there is a possibility of its having been a prehistoric hunting ground.

Two test pits were excavated on the tank bund, in the southern sector of Mapagala (see report by Gunasiri, PGIAR Archive). Two major factors were revealed through these ex cavations:

(1) Finds of earthenware pottery belonging to a settlement prior to the construction of the tank bund.

(2) That the main wall of Mapagala was constructed before the construction of the tank bund.

THE EXCAVATION OF 1990

A test ditch 29x2m, which covered the main wall of the western axis of the Mapagala North rock and the second wall, was selected for excavation this year. In the selection of the excavation site, attention was paid to the fact that walls on the western section were still intact, and that it was necessary to have some idea of the nature of constructions and evolution of local settlements.

Methods

The context matrix system was followed as the method of excavation (Hanis 1979). The area belonging to three terraces (malakas) was marked in a single line, as a ditch of 29x2m. These terraces were marked A-B-C and divided A 100-115, B 88-99 and C 86-88. The south-north axis was marked from 300 upwards, towards the north, and the west-east axis from 100 upwards and downwards, towards east and west respec tively. Thus, in reporting a square meter, a number was in cluded (300/100 etc.).

Contexts which were extensively thick were divided into sub-numbers or arbitrary strata of 20cm (e.g. context 1 - level 1). Context numbers were given according to the texture of natural and artificial soil layers (colour and composition); pits, cut marks, special features (brick walls, stone walls, termitaria,etc.) etc. Accordingly, for excavation ditch A context no. 1-28, B 30-41 and C 50-53 were

Results

According to the study of stratification in this excavation, the strata can be divided into seven consecutive phases. They have been tentatively named according to their relation to the main ‘cyclopean’ wall.

Phase I: Pre-construction phase.

The excavation did not give evidence of prehistoric activity at the site. The first period is depicted in context 7 (see fig. 9:9 and 9:10), the first undisturbed cultural deposit formed on the gravel layer (context 8). It contains Black-and-Red Ware to a relatively small extent only. The nature of a settlement deposit is evident. The main stone wall (context 34) is built in a cut (context 18) through context 7. Therefore it can be considered that the people who lived before the construction of the stone wall are represented by context 7. Also, lumps of iron slag were found. Although it could be surmised to belong to the protohistoric and Early Historic period, the 14C-dating of context 7 gives evidence of a 3rd century settlement (see below). Slag has also been found in large quantities around Mapagala, especially towards the west, at site SO. 66. The dating of the latter site is yet unknown.

Cut marks, which could be those made for posts, and the fill in those postholes, were given numbers 24, 25, 41 and 37. These holes may be contemporary with or prior to the period of construction of the main wall. Though this factor is not helpful in our hypothesis, our personal view is that this was done prior to the construction of the wall.

Phase II: Construction phase

The major and the minor terrace walls (contexts 34,33) were built after the cut context 18 had levelled the ground, and behind the main wall soil was filled to form a terrace (con texts 11, 10,14, 15, 12, 6, 5, 28, 23, 17, 9, 22, 21, 19, 20 and 3) (see fig. 9:9 and 9:10). Black-and-Red Ware was found sparsely from these contexts. This can be identified as the main construcion stage of Mapagala.

Phase III: Occupational phase

Contexts 38 and 52, below the main terrace, have been iden tified as occupational deposits. These are cultural layers where plain Red Ware and tiles are found in large quantities and Black-and-Red Ware only in small quantities. The pieces of tile found near the wall, on either side, provide evidence of the existence of some structure, like a roof, along the wall. The 14C-dating of context 38 indicates occupation in the Kasyapan period.

Phase IV: Abandonment

Contexts 2, 32 and 51 have been interpreted as a period of abandonment. No clear signs of settlements have been retrieved from these contexts.

Phase V: Reconstruction phase

Above the natural layer (context 2) there are traces of rec onstruction of the main wall, in contexts 16, 4 and 13. This probably belongs to the post-Kasyapan period and can be considered the last phase of use depicted in this excavation. No idea can be formed as to the duration of this period. According to artefacts found in context 2, it can be considered as dating back at least to the 10th century.

Phase VI: Destruction

This phase is represented only by the stones fallen from the main wall (context 35).

Phase VII: Post-destruction phase

There are traces of settlement remains also in the last strata (contexts 1, 30, 50) but the evidence is not clear enough to identify the nature of such a settlement. However, instead of distinctive features of rural and urban settlements, what is found are those common to monastery settlements.

Pottery

The collection of pottery discovered from Mapagala can be divided into three groups of wares. 1. Black-and-Red Ware 2. Red Painted Ware and 3. Plain Red Ware.

Only a very small quantity of Black-and-Red Ware has been found. Among them there are only two identifiable rim sherds, while those remaining are body sherds. The technol ogy displayed is very poor, not as high in quality as those found at the Gedige, in Anuradhapura, or the Jetavana, etc. They are more like some of the earthenware bowls from the Ibbankatuva megalithic culture site.

Red Painted Ware too, has been found in very limited quantity. The outer coating is red and has a composition of clay. The pieces seem to have been made of a mixture of finely sieved clay, and are similar to the Red Painted Ware found at other places in Sigiriya. This Red Ware can be divided into two types: Red Ware with a very delicate finish, and with a very rough finish. The clay composition of the first type is very fine and mainly used for very small ware. The clay content in the second type of pottery is very low and the finish not so advanced. For a study of diagnostic rim sherds found in almost all contexts, the pottery can be divided into several basic types. The speciality of contexts 7 and 38, where Black-and-Red Ware are found, is that these artefacts are similar to pottery found from sites like the Early Historic Gedige (Deraniyagala 1972), Tissamaharama (Kuna 1985), etc. These finds are limited to artefacts such as urns, plates, pots, etc. The cultural characteristics revealed through contexts 1, 2, 32, etc. show a continuity from the middle-Anuradhapura period up to the post-Anuradhapura period. However multi-period relation ships too, are to be found from certain contexts, i.e. context 32. Certain types represent the early Anuradhapura period.

14 C-datings

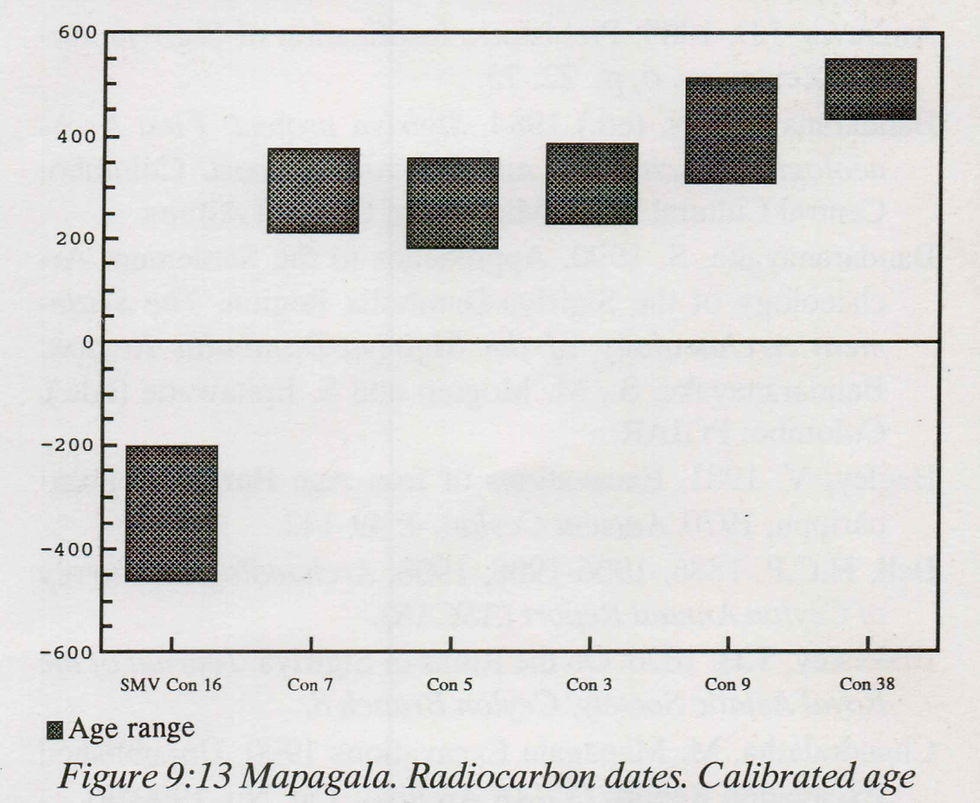

Charcoal samples from five different contexts were sent to Sweden for analysis (see "14C-datings" this volume). Context 7 is a pre-constructional settlement layer; contexts 5 and 3 are fill belonging to the construction phase; context 9 is fill belonging to the construction phase, or the occupation phase; and context 38 belongs to the occupation phase.

The results (see fig. 9:13) must be considered to be fairly coherent - and hence reliable - and fix the construction and first occupation phases between the 3rd and late 5th centuries.

CONCLUSION

It was possible to gain new knowledge of the chronology of the settlements in Mapagala through the excavations con ducted on the North rock of Mapagala in 1989, and at the foot of the rock on the west side in 1990. Although there were not sufficient facts to identify separately the structural relation ships among settlements, it was possible to distinguish the qualitative features of different settlement layers.

There are three common factors that emerge from the ex cavation on the summit (test excavation no. 2)

1. The absence or destruction of strata belonging to the historic period.

2. Extensive finds of quartz, with microlithic imple ments from all contexts.

3. Finds of Black-and-Red Ware from the lowest con text (no. 3).

The fact that quartz and microlithic implements are found in large quantities and brickbats, tiles and other finds in very small quantities from the remaining soil strata, shows signs closer to an earlier period than the historic. Therefore informa tion regarding a historic period is not revealed through the strata on the summit. The existence of Black-and-Red Ware in the bottom context and quartz from all the contexts, has given rise to certain complicated conclusions. That is because the economic structure of the society which used microlithic implements was a society of hunters and food gatherers, while the society that produced Black-and-Red Ware was an ag rarian economy. Two suggestions can be made to solve this problem.

Firstly, the test pits selected for the excavation are not sufficient to solve all the problems. There is insufficient ev idence upon which a complete vision of the social structure of those societies could be built, while the structural relationsip of those finds which were discovered is not clear either. The discovery of Black-and-Red Ware from the lowest bottom strata, while quartz is found everywhere, poses the question whether the strata were turned upside down at a certain stage. But it is clear that these soil layers are not those brought from outside. On the whole, the excavation is insufficient to throw light on these basic questions.

Secondly, the entire stratigraphic sequence shows one co mmon characteristic. The above finds are seen mixed in vary ing quantities in all the strata. There is a similarity between the stratum in colour and composition too. This shows that it is not possible to highlight the transitory features of settlements. What is revealed very clearly are not distinctive features that separate one settlement from the other, but those which show inter-relationship and interdepedence between them. This is evident not only in socio-economic factors, but in the technique as well. Such features are also found in places like Dambulla and Pidurangala (Bandaranayake 1990: 23).

In the trench excavation (see fig. 9:9 and 9:10) conducted on the west side of Mapagala (1990), the order of strata, various activities, the order of pottery and the results from

14C-analysis were observed and upon that data conclusions were drawn. There is a settlement sequence here which can be divided into three main categories.

1. Protohistoric settlement

2. Early Historic settlement

3. Middle Historic settlement

Proto and Early Historic ‘pre-wall’ settlements are rev ealed through context 3 in test pit 2 (1989) and context 7 of the trench (1990), as well as through the stratigraphic sequence, from context 24 upto context 16 in test pit 1 of the Sigiri Mahavava bund excavation, in 1989 (see report by Gunasiri in the PGIAR Archive). Although the factors revealed through the excavations conducted below the rock do not relate direct ly to protohistoric settlement features, these are confirmed through the excavation on the summit of the North rock. There is no similarly between the Black-and-Red Ware found on the summit and those found below.

The Black-and-Red Ware remains found on the summit are similar to the megalithic cultural ware found in Pomparippu (Begley 1981) and Ib- bankatuva-Polvatta (Karunaratne this volume and forthc oming). The Black-and-Red Ware found in the 1990 trench show a certain similarity to Early Historic pottery. They are very similar to those pottery finds discovered from sites like Anu- radhapura Gedige (Deraniyagala 1972), and Tissamaharama . (Kuna 1985). When these similarities and dissimilarities are considered, two interpretations can be made about the original settlements, depending on the possibility of arriving at definite conclusions.

1. The strata on the summit (especially context 3) repre sents the megalithic culture. megalithic cultural group using microlithic implements in a mixed economy.

Secondly, the major settlement period is the one repre sented by the main wall. This shows a stage of a more de-

2. The first cultural layer below (context 7) represents the Early Historic period.

The iron slag here is a special feature. The fact that it is found from both strata may be due to some technological relationship. But the existence of microlithic implements and quartz, as on the summit, is not evident from the strata below the rock. And thus it is clear that of the two, the settlements on the summit are the older. It cannot be concluded with certainty that these quartz pieces are remains of a prehistoric usage. Their utility and related activities are not clear.

Firstly, what is evident from this is the fact that qualitative characteristics of one settlement are reflected in some manner in the other settlements as well. The continuity of and inter relationship between the technology found in the prehistoric settlements and the technology found on the summit, shows a certain connection. But the settlement below is the second stage of its evolution. As a rough reference to the people of the first settlement, it can be said, as a suggestion, that they were a megalithic cultural group using microlithic implements in a mixed economy.

Figure 9:13 Mapagala. Radiocarbon dates. Calibrated age ranges from cumulative probability, one sigma (68.26%).

CalibETH 1.5b (1991). In the diagram is included age range for sample from cultural deposit south of Mapagala, under

the Sigiri Mahavava bund (SMV Con. 16).

Secondly, the major settlement period is the one repre sented by the main wall. This shows a stage of a more developed and organized nature. According to stratigraphical evidence discovered, it can be concluded that the vast con struction stage, which included the main wall of Mapagala, be longs to the second stage (see fig. 9:10). However, evidence of its activities apd utility was not revealed, therefore it cannot be exactly determined whether it is a fortress or a monastery. The phase represented by contexts 16, 13 and 4 (see fig. 9:9 and 9:10) can be considered a major reconstruction phase. Rough ly, it can be considered a result of activities in the 5th century.

Characteristics of monastic settlements can be observed in a study of subsequent stages, contexts and pottery. Although such traits are not distinctive from each other, this place can be considered a monastic centre upto the 9th and 10th centuries, in view of the fact that a monastery complex like Mahanaga Pabbata Vihara is situated on the west of this complex. This is confirmed by the discovery of ‘attani pillars’ close to this site.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The co-operation extended by Manel Fonseka, who furnished Archaeological Administrative Reports and other necessary particulars, was very helpful in this study.

REFERENCES

Andrews, J.B. 1909. Prehistoric fortification of Sigiriya. Sp- olia Zeylanica. 6, pt. 22: 75.

Bandaranayake, S. (ed.) 1984. Sigiriya project: First Arch aeological Excavation and Research Report. Colombo: Central Cultural Fund, Ministry of Cultural Affairs.

Bandaranayake, S. 1990. Approaches to the Settlement Ar chaeology of the Sigiriya-Dambulla Region. The SettlementArchaeology of the Sigiriya-Dambulla Region.Bandaranayake, S., M. Mogren and S. Epitawatte (eds.). Colombo: PGIAR.

Begley, V. 1981. Excavations of Iron Age Burials at Pom- parippu, 1970. Ancient Ceylon. 4: 49-142.

Bell, H.C.P. 1886, 1906-1908, 1908. Archaeological Survey of Ceylon Annual Report (ASCAR).

Blakesley, T.H. 1876. On the Ruins of Sigiriya. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Ceylon Branch 8.

Chandralatha, M. Mapagala Excavations 1990. Unpublished Excavation Report. PGIAR Archive. Cat. No. 1990/06.

Deraniyagala, P.E.P. 1973. Some sidelights on the Sinhala monastery-fortress of Sihagiri. Spolia Zeylanica. 26, pt. 1: 69-75.

Deraniyagala, S.U. 1972. The Citadel of Anuradhapura 1969: Excavations in the Gedige Area. Ancient Ceylon 2\ 48- 164.

De Silva, R. 1967/68, 1968/69. Archaeological Survey of Ceylon Annual Report (ASCAR).De Silva, R. 1970. Sigiriya. Colombo: Department of Ar chaeology.

Geiger, W. 1969. Madhyakaleena Lanka Sanskruthiya. (Sinh, transl. of "Culture of Ceylon in Medieval Times" by M.B. Ariyapala) Colombo: Gunasena.

Godakumbura, C.E. 1964/65. Archaeological Survey of Ce ylon Annual Report (ASCAR).

Godakumbura, C.E. 1976. Architecture of Sri Lanka. Colom bo: Ministry of Cultural Affairs.

Harris, E.C. 1979. Principles of Archaeological Stratigraphy. London: Academic Press.

Ilangasinghe, M. 1987. Dambulla Viharaya. Kelaniya (Wa- ragoda): Empier Printers.

Indrapala, K. 1965. Samaja Torathuru. Anuradhapura Yug- aya. Liyanagamage, A. and R. Gunawardhana (eds.). Ke laniya: University of Vidyalankara.

Kuna, M. 1987. Local Pottery of Anuradhapura: A Way to its Classification and Chronology. Pamatky Archeologicke LXXVIII:5-66.

Lawrie, A.C. 1898 (1988). A Gazetteer of the Central Pro vince of Ceylon. Vol I and II. Colombo: National Mus eum.

Liyanagamage, A 1965. Anuradhapura Yugay a. Liyanagam age, A. and R. Gunawardhana (eds.). Kelaniya: University of Vidyalankara.

The Mahavamsa. Geiger, W. (ed). 1950. Colombo: Govern ment Press.

Paranavitana, S. 1970. Inscriptions of Ceylon. Vol 1. Colom bo: Department of Archaeology.

The Rajawaliya. Suraweera, A.V. (ed) 1976. Colombo: Lake House Investments Ltd.

Ranawella, S. 1984. Epigraphy. Sigiriya Project: First Ar chaeological Excavation and Research Report. Bandar anayake, S. (ed). Colombo: Central Cultural Fund, Ministry of Cultural Affairs.

Seneviratna, A. 1983. Golden Rock Temple of Dambulla. Colombo: Central Cultural Fund.

Seneviratne, S 1984. The Archaeology of the Megalithic- Black-and-Red Ware Complex in Sri Lanka. Ancient Ce ylon. 5: 237-307.

Seneviratne, S. 1990. The locational significance of early iron age sites in intermediary transitional eco-systems: A preliminary survey study of the upper Kala Oya Region, North-Central Sri Lanka. The Settlement Archaeology of the Sigiriya-Dambulla Region. Bandaranayake, S., M. Mogren and S. Epitawatte (eds.). Colombo. PGIAR.

Tissa Kumara, A. 1990. Perani Lakdiva Atthani Vidhy. Kel aniya: University of Vidyalankara.Wimalaratne, W. A 1984. Palath Seema Mammawath Ha Matale Ithihasaya. Ithihasika Matale. Wijesuriya, S.S. (e-

d.). Matale: Matale District Cultural Board.

Appendix: Context Descriptions

Test excavations in 1989. Test pit No. 1

The excavation was done down to bedrock and the depth was 80cm at the end of excavation. This is described from the lowest context up to the surface stratum from the bedrock (see section drawing fig. 9:9).

Context No. 1

This is a reddish brown (2.5 YR 4/4) layer with a high composition of sand subject to erosion. It is very fine and soft. Slopes from the north to the south. Texture: Clay 55%, Sand 40%, Silt 4%, Pebbles 1%

Cultural finds are very rare in this context. Thickness 70 cm. Excavations were done upto 10cm, according to artificial strata. At the last stage (6th stage) a few brickbats, a piece of tile and small fragments of pottery were discovered.

Context No. 2

A reddish brown stratum (2.5 YR 4/4) with a high quantity of pebbles. Moisture was high and hence the soil was soft. Texture: Clay 50%, Pebbles 40%, Sand 8%, Small Pebbles 2%.

This takes a gradient from north to south. Cultural artefacts are a little more than those in context 1. Very limited quantity of potsherds was found. All were body parts made thin by erosion. There was some quartz and granite too.

Test pit No. 2 Context No. 1

Dark reddish brown and very fine (2.5 YR 3/4). Sand grain is very rare. Very small fragments of potsherds, a few tiles and brickbats were found here. Microlithic artefacts were found too. Slopes from north to south. Texture: Clayey soil 70%, Cultural debris 13%, Sand 5%, Silt 5%

Context No. 2

A dark reddish brown soil with a little fine sand (2.5 YR 3/4). A fine soil layer with high content of clay, 70cm thick. From the upper part, level 1-5, small brickbats, potsherds, tiles, quartz and two lumps of iron slag were found. From level 5 no other remains were found except quartz. Slopes from north to south. Texture: Clayey soil 65%, Sand 20%, Cultural debris 10%, Silt 5%.

Context No. 3

A reddish brown (2.5 YR 4/4) and lighter brown than context 2. Full of fine sand. Takes a southern gradient from the north; thickness is 10cm. Washed away stratum. Microlithic artefacts were discovered in large quantities and Black-and-Red Ware to some extent. Texture: Clay 75%, Sand 20%, Silt 5%, Cultural debris 5%.

The excavation in 1990.

Excavations were done up to the sterile gravel, to a maximum depth of 3m and minimum depth lm. For convenience of reporting, each context from the bottom up to the surface (recent period) is described upwards.

Context No. 1

This is the humus soil on the surface and the surface soil layer of the excavation ditch. Dark brown. 7.5 YR 3/4. Tex ture: Clay 83%, Silt 10%, Sand 5%, Cultural debris 2%.

Context No. 2

An alluvial soil layer. Dark brown. 7.5 YR 4/4. Texture: Clay 77%, Silt 15%, Cultural debris 5%, Sand 2%, Stones 1%.

Context No. 3

A filled soil layer about 50cm thick, where small stones are found in plenty. Context 4 seems to have been built on this. Grayish-brown layer. Texture: Clay 33%, Silt 2%, Cultural debris 5%, Sand 5%, Pebbles 5%, Small stones 50%.

Context No. 4

This is a structure located behind context 34 (main wall) and built at a secondary stage. It seems that context 4 is built upon context 3.

Context No. 5

This layer, which is about 30cm thick, slopes westwards, extending throughout the entire trench. Reddish brown .7.5 YR 6/5. A layer filled with soil for the construction of the terrace. Texture: Pebbles 35%, Clay 30%, Fragmented stones 21%, Sand 8%, Cultural debris 5%, Silt 1%.

Context No. 6

A layer extending up to the wall from 300,302,107 limit. A filled layer about 50cm thick. Yellowish red. 7.5 YR 6/6. Texture: Clay 67%, Sand 6%, Pebbles 4%, Cultural debris 2%, Silt 1%.

Context No. 7

A soil layer upon context 8. Situated between 300/102-

109 and 302/102-109. Strong brown. 7.5 YR 5/6. Average thickness about 20cm. Among cultural debris found from this layer are charcoal, tiles, potsherds, etc. People who settled in this context have dug context 34 and built the main wall. Texture: Clay 75%, Sand 10%, Cultural debris 5%, Granite 4%, Silt 3%, Other 3%.

Context No. 8

This is the lowest bottom soil layer. Reddish brown in colour (7.5 YR 5/4). Both context 39 found in the second excavation ditch, and context 53 found in the third ditch to gether form the same layer. Context 33 and 34 walls are built upon this layer, which slopes to the west from the east.

W.A. KUMARADASA

Context no. 9

This is the sub-layer on the surface of the above mentioned pit. Mostly gravel is seen. Reddish brown. 75 YR 6/8. Texture: Stones 75%, Clay 14%, Sand 5%, Pebble 5%, Silt 1%.

Context No. 10

This too is filled soil in the above pit. Dark brown. 75 YR 5/6. Texture: Clay 43%, Sand 35%, Pebbles 21%, Cultural debris 1%.

Context No. 11

Filling of the pit cut for the construction of context 34 wall. Reddish brown. 5 YR 4/4. Texture: Clay 90%, Cultural debris 5%, Silt 3%, Sand 2%.

Context No. 12

A sub-layer with a thickness of about 5cm extending up to the wall from 300,302/106 limit. Yellowish red. 5 YR 4/6. A filled soil layer. Texture: Clay 73%, Sand 20%, Pebbles 5%, Silt 1%, Cultural debris 1%.

Context No. 13

The soil filled in the pit cut for the construction of context

4. Brickbats are common. Dark reddish brown. 7.5 YR 3/4. Texture: Clay 50%, Cultural debris 40%, Sand 5%, Silt 5%.

Context No. 14

The surface layer filled in the above pit parallel to context

7. Dark, reddish. Texture: Clay 87%, Sand 5%, Pebbles 4%, Small stones 2%, Cultural debris 2%.

Context No. 15

A layer of about 5cm upon context 7. Spread over sub squares 302/100-302/108. Small stones mainly found. Dark brown 75 YR 4/4. A filled soil layer. Texture: Clay 50%, Small stones 40%, Pebbles 4%, Sand 4%, Silt 1%, Cultural debris 1%.

Context No. 16

A cut mark in the pit dug for the construction of context 4 wall.

Context No. 17

Boulders in the terrace fill, deposited before context 9. Context No. 18

This is the cut mark of the foundation cut for construction of the main wall, context 34. This is dug from context 7. It seems filled with sub-layer contexts 10,14 and 11.

Context No. 19

Filled soil of the above mentioned pit. Situated between 300/111-112. Small stones are found in large quantities. Yel lowish red. 5 YR 5/8. Texture: Small stones 70%, Clay 9%, Pebbles 5%, Sand 5%, Cultural debris 1%.

Context No. 20

A filled soil layer on the surface of the above pit. Reddish yellow. 7.5 YR 6/6. Texture: Pebbles 41%, Small stones 25%, Clay 20%, Sand 16%, Silt 2%, Cultural debris 2%.

Context No. 21

Cut mark of a pit dug from context 5 into context 8. Context No. 22

A sub-stratum situated below context 3 and upon context 9. Strong brown. 7.5 YR 6/6. Texture: Sand 52%, Clay 40%, Pebbles 5%, Silt 2%, Cultural debris 1%

Context No. 23

A sub-layer situated on the lowest bottom of context 28. Dark brown. 75 YR 5/6. Texture: Sand 90%, Pebbles 5%, Clay 5%.

Contexts No. 24 and No. 25

Context 24 is a cut pit. Context 25 is its cut mark. It has been cut into context 8 from context 22. Yellowish red. 5 YR 5/8. Texture: Clay 50%, Sand 50%.

Contexts No. 26 and No. 27

Context 26 is a pit dug with context 27 as the cut mark. It was noted that it is cut into context 8. Dark brown soil; 7.5 YR 4/4. Texture: Clay 46%, Sand 20%, Grain sand 20%, Pebble 10%, Silt 3%, Cultural debris 1%

Context No. 28

A cut mark. The pit cut into context 8 is filled with sub layers, context 23 and 9.

Context No. 30

This is the surface soil layer between 90-97. Strong brown in colour. 7.5 YR 4/6. Thickness is 5 cm.

Context No. 31

This is a termite hill, found at the foot of the main wall between 97-100.

Context No. 32

An alluvial soil layer about 50cm thick. Dark brown. 7.5 YR 4/4. Cultural debris found in large numbers, among which are Black-and-Red Ware. Appears to be a few stones fallen from the main stone wall (context 34). Texture: Clay 70%, Cultural debris 20%, Silt 6%, Sand 4%.

Context No. 33

This is the small wall on the second terrace. Built upon contexts 39 and 53. This wall, about one meter in height, is medium sized compared to the main wall. The measurements of the blocks of stone used for its construction are appr oximately 1.50mxl.00mx0.80m. The type of stone, used in the main wall, is used here too.

Context No. 34

This is the main stone wall, 3.34m high and 1.80m wide. Each stone used generally measures about 2x1x1 l/2m. A single stone may weigh approximately 5 tonnes. This wall is constructed by connecting large, live stones. Of the walls built round Mapagala North rock, which are largely washed away, only this wall is left. Built entirely of granite.Context No. 35

A few pieces of stone from the main wall, fallen upon context 32. Sunk up to context 38. Found spread over a space of about 3m, 180cm away from the main wall.

Context No. 36

A line of stones which shows marks of a construction upon context 32. Located horizontally between 302/94-95. Built of stone about 20cm in diameter.

Context No. 37

A cut mark dug into context 39. Probably a garbage pit. Context No. 38

An alluvial soil layer between contexts 39 and 40. About 20cm thick. Dark brown. 7.5 YR 4/4. Cultural debris found in large numbers: Black-and-Red Ware, potsherds, tiles and ch arcoal. The majority of Black-and-Red Ware is found from this context. According to the cultural artefacts and location of this layer, it can be that this shows a stage of decay of the wall. Texture: Clay 50%, Sand 20%, Cultural debris 20%, Silt 5%, Small stones 5%.

Context No. 39

Same as context 8 and 53. Context No. 40

This is the soil layer upon the one on context 39. Expands upto 97-92/300. On the 302 front it ends at 94. It has the appearance of a pit, but cannot be considered as soil filled in apit because it is very hard, with kabook too. Therefore it is not certain whether it is a transition of the context 39 pebble layer itself. It cannot be decided whether it is a decayed kabook stone. Yellowish red. 5 YR 5/8. Texture: Kabook 75%, Clay 15%, Pebbles 15%, Sand 5%, Cultural debris Nil.

Context No. 41

Soil filled in the pit dug for context 37. Dark brown. 7.5 YR 4/2.

Context No. 50

Same as contexts 1 and 30. Context No. 51

An alluvial soil layer on context 52. Dark brown in colour and 30cm thick (7.5 YR 4/4). Among cultural debris found here are Black-and-Red Ware and Red Ware. This layer, being a natural deposit, resembles contexts 2 and 32.

Context No. 52.

An alluvial layer on context 53. Dark brown in colour. 7.5 YR 4/4. This layer, which is 45cm thick, had a steep slope towards the west. The Black-and-Red Ware, Red Ware and brickbats are similar to those found in context 38. According to the nature of the deposit of cultural debris, this layer has some similarity with context 38 and 7. Texture: Clay 55%, Sand 20%, Cultural debris 18%, Silt 7%.

Context No. 53

Same as contexts 8 and 39.

Comments