The Archaeology of Irrigated Agriculture. A Case Study ofVavalavava - Sigiri Mahavava Irrigation Sys

- ADMIN

- Aug 16, 2021

- 26 min read

EVA MYRDAL-RUNEBJER

INTRODUCTION

The present study is an archaeological case study of an aban doned pre-modem irrigation system in Sigiriya, which is in the northern sector of the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka. The full field report on this work is to be presented in a separate volume. What appears here is only an outline of the study and a discussion of its preliminary results.

Previous discussions regarding pre modem irrigation tech nology and wet-rice cultivation in Sri Lanka have focused on dating and technological development and decline in an over all Dry Zone perspective. Apart from the structures visible on surface - most often documented by dedicated engineers and surveyors - the principal basis for such studies has largely been inscriptions and literary sources.

In contrast, the focus in the present study is on a given system of moderate size, with the possibility of relating the data to rural and urban settlements and elite secular and religious structures. The source materials here are the material remains themselves, and the methods are archaeological - that is, field surveys and test excavations to obtain a frame for dating and information about constructional features.

Written sources regarding the construction of this specific system have so far not been found. A few inscriptions can be used to infer a terminus ante quern for part of the system. Moreover - as no historian will deny - in any situation written source material will only provide us with part of the informa tion we seek when we discuss dating, technology and produc tivity potential. The material remains are manifest functional history, the interpretation of which, however, is unfortunately not always obvious, as will be clear from the discussion that follows.

The field survey of part of the system the Vavalavava canal commenced in 1988, although no results furthering a function al or chronological understanding of the Vavalavava canal were reached at that time (Mogren 1990:59). In 1989 two minor trenches were taken up in the tank bund itself, address ing the question of chronological relationship between a cyclopean wall connecting to the tank bund and the stone pitching of the bund (Gunasiri, PGLAR archive report 1989). The canal survey was taken up again during a two week

Figure 12:1 Research area ofVavalavava - Sigiri Mahavava irrigation system survey.

part-time survey in 1990, by the present writer, two assistants and one to two labourers. It was continued during a full SARCP field season in 1991 by a single Lankan archaeologist, one assistant, the Swedish consultant and from two to ten labourers. In 1992 the field team consisted of eight Lankan archaeologists, the Swedish consultant and up to eight lab ourers.

OBJECTIVES

Population, productivity and the organization of labour The key words in this study are human labour and productive potential. The study tries to define the archaeological remains of this irrigation system in terms of function, technique of construction and dating, potential of production and labour investment.

Based on such data analysed in relation to the settlement pattern, it is possible to address three important questions regarding the premodem society of the area during given periods:

(1) the maximum size of the population that could be supported by the system - an upper limit of the system’s production capacity.

(2) the control and appropriation of agricultural produce (the level of which is basically testified to by all forms of non-agricultural construction, in the present area and within the time-frame covered by the study, from peasant houses to the monasteries and iron production sites).

(3) the control and organization of labour.

The first of these questions will be addressed within the frame of the study discussed below. The second, which re quires a more in-depth study of rural settlement sites, along with the related third question, will only be discussed in the coming report as an outline of a possible field strategy and methodology.

HYPOTHESES AND METHODS

Questions at issue

It is a widely recognized fact that a timely supply of water is the most important yield increasing factor in wet-rice cultivation in semi-dry tropical regions like the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka and southern and eastern Tamil Nadu. Artificial irriga tion is a means of establishing control over the water supply. At the same time, while irrigation is the key factor, it is definitely not the only yield-increasing factor. It allows for a variety of productivity-increasing practices to be developed, as shown for example by David Ludden regarding Tamil Nadu and Francesca Bray regarding East and South East Asia (Ludden 1985; Bray 1986).

The difference between the small scale irrigation system based on local precipitation on the one hand and the macro irrigation system, with feeder canals enlarging the catchment area on the other, is to be noted however. They have, as pointed out by many scholars and obvious to every peasant, different implications regarding possible return and labour in vestment and the organization of labour.

Broadly speaking we could distinguish the following pr emodern agricultural possibilites (with different supportive capacities) in the study area (see Myrdal this volume):(1) Polyculture swidden cultivation combined with other forest-based food procurement activities such as gathering wild plants, honey collection, hunting and trapping.

(2) Paddy cultivation based on village tanks which, owing to the irregular supply of water, often has to be combined with swidden cultivation and related practices. This combination still forms the most important subsistence pattern for the pe asants in the study area.

(3) Paddy cultivation based on a macro system of irriga tion, with a larger and more secure water supply which would make paddy cultivation the most important food procurement technique. Owing to the man-created, wet-rice agricultural landscape, several forest-bound food procurement practices would then be ruled out.

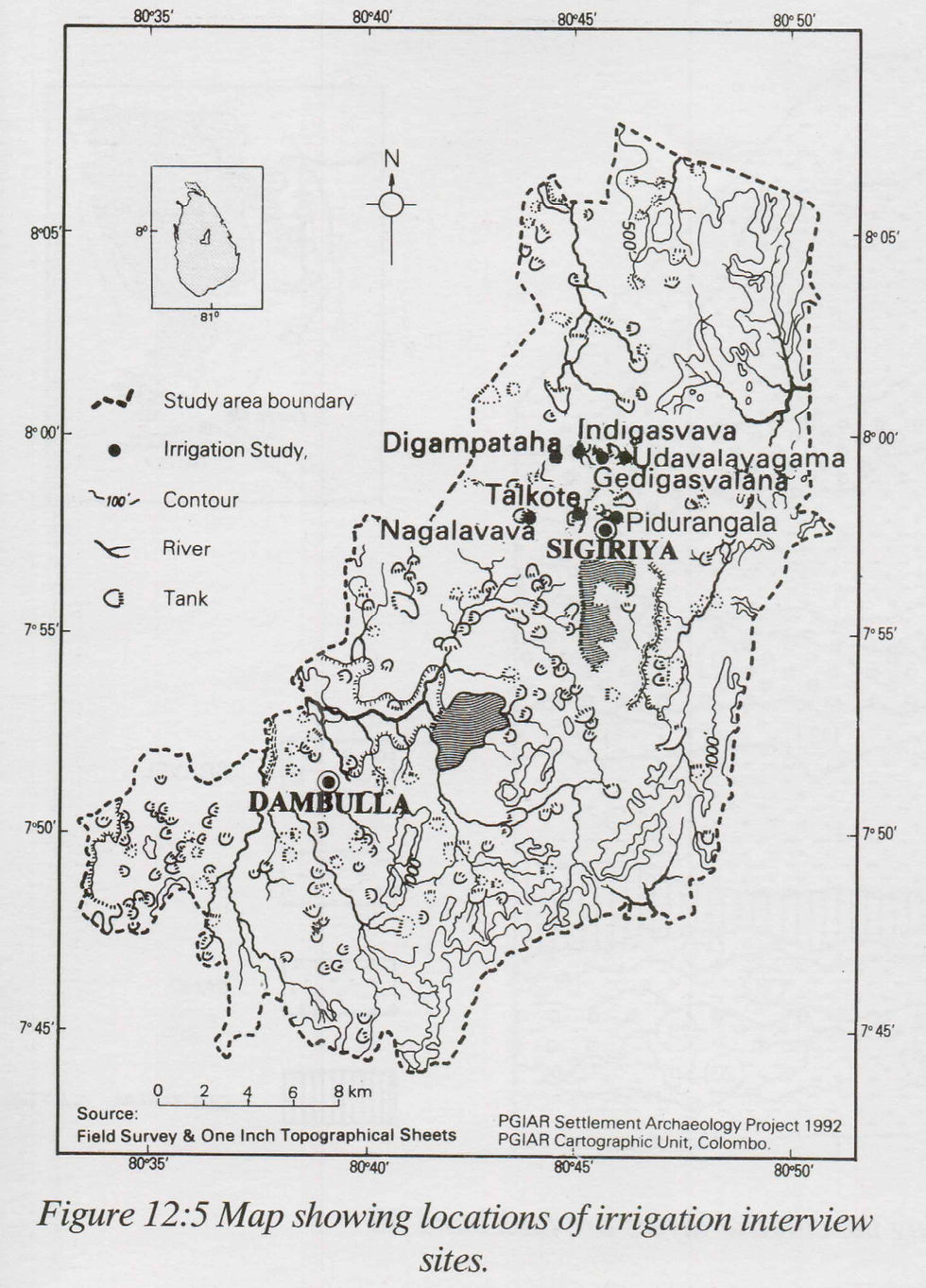

To understand the material pre-requisites of irrigated ag riculture under small scale systems, a series of interviews have been carried out with elderly male villagers (mostly former vel vidanes) in eight villages in the Sigiri Oya basin. These have been followed up in Talkote village by field surveys of village tanks, small few-family tanks (vav kotu) and micro tanks (te rmed amuna by the villagers ) in the paddy fields.

The ethno-archaeological study in Talkote village also pr ovided information regarding paddy cultivation and main tenance work.

MACRO-IRRIGATION SYSTEMS IN THE SIGIRIYA AREA

Macro-tank: Sigiri Mahavava

In the Sigiriya area, the only premodem irrigation system so far discovered which has the potential of increasing the supp ly of water above the localised village tank level, is the Sigiri Mahavava itself and the three canal systems we now know of, that might have been functioning as supply canals to the tank.

As Assistant Superintendent of the topographical survey of the Sigiriya area in 1898, D. Blair was able to establish the outline of the Sigiri Mahavava bund as it is known even on the present topographical map of the area. This was an improve ment, as compared to Blakesley’s survey of the tank bund in 1874, when the bund was traced down to the pathway between Palutava and Polattava only, and the presence of the southern half of the tank was unknown (Blair 1898).

Supply canals to the east of Sigiri Mahavava: eastern and western canal systems

Commenting on the large size of the tank, Blair suggested that for the Sigiri Mahavava to have functioned properly it would have needed a connection to a wider catchment area than its natural topography affords. He went on to suggest a connection to the Kiri Oya basin, east of the tank. H.C.P. Bell also mentions a canal from Vavalavava as the connection between the Kiri Oya basin and Sigiri Mahavava, and cites the oral tradition in the area that this canal was constructed by King Mahasen (276-303 CE) (Bell, Fernando, Moysey 1914).

The southern extension of an abandoned canal from Va valavava, built over Kiri Oya, was mapped by surveyors be tween 1897 and 1902, and in the 40’s the northern extension of the eastern canal bund and the western, partly parallel canal bund, was depicted in the revised map. In 1990 Chandana Ellepola presented the idea that water was brought from Va valavava to Sigiri Mahavava through a connection between the eastern and western canals (Ellepola 1990:178). If water was brought from the Vavalavava canal to Sigiri Mahavava, this is a trans-basin canal which connected the upper Kiri Oya catchment with the Sigiri Oya basin, and which may thereby have fed not only the vava but directly irrigated the land between the canal and the Kiri Oya itself.

Looking at this closely, we notice that there are, in fact, two systems: one, the eastern canal system, which starts at Vavalavava and continues north, according to the topographi cal map, ending about 800m east of the northern most part of Sigiri Mahavava, on top of a low ridge that constitutes water shed between the canal and the vava\ the other, the western canal system, which starts midway of the eastern canal, runs parallel to it for a short stretch and holds a seasonal stream on its western side. The stream ultimately falls into Sigiri Ma havava.

The preliminary field survey in 1990 and 1992, the recent contour mapping by the Survey Department (ground truth not established), and the l/2m interval contour mapping carried out for PGIAR by a licensed surveyor and leveller in 1992, have not given any evidence that water from the Kiri Oya actually passed into the western system, or that the two canals were connected (see fig. 12:2 and 12:3). The canal bed surface at the end of the western bund is situated about 1.5m above the eastern canal bed, and no indication of a southern continuation of the western bund has so far been found.

The present canal bed surface of the western bund is about 1.2m over the height above mean sea level of the documented ancient sluice in Vavalavava. The present western canal bed surface is about 2.6m above the canal bed base of the trench taken up 1.5km to the south in the eastern canal.1

The western, shorter canal might therefore have had two purposes. One to collect run-off water from the slightly ea stwards slope and further north, hold the water of the stream, ultimately draining into Sigiri Mahavava; and/or to protect the eastern bund from destruction by run-off water.

The eastern canal from Vavalavava might also have had a double purpose: one (which might have been its initial func tion) to irrigate the land between the canal and Kiri Oya. This is an area where it has now been discovered, large scale and technically advanced iron production had been developed du ring the 2nd century BCE and the 3rd century CE (see Fo- renius and Solangaarachchi this volume); the other, to supply the Sigiri Mahavava with water, i.e. the water that was left could have drained into the northern most part of the Sigiri Mahavava.

Whether the eastern canal really joins the northern most part of the tank however is not yet clear. Judged by present day topography it could have continued north, through a present system of minor tanks, and at the end joined Sigiri Oya just south of Hirivadunnavava. The field survey of the northern part of the eastern canal has not been completed at the time of writing.

The trenching of the eastern canal in 1992, in three places, gave evidence of an initial heavy sedimentation of the canal bed. The sediment indicates erosion from the bund and natural slope above the canal by rain, rather than sediment transported and settled in running water. Based on these facts, we have to ask whether the eastern canal was ever put into use or, alternatively, if it had functioned for a very short period only. Soil sample analyses for diatoms in the canal sediment, and char coal dating now under way will hopefully give a more com plete answer than we could gain from ocular observation only.

Ancient sluice at Vavalavava

Preparing the restoration of Vavalavava, the Irrigation De partment documented an ancient sluice at the site where they constructed the new one.2 The modem sluice was constructed

10 feet above the ancient one. Comparing the Irrigation De partment plan with the topographical map, it was indicated that this ancient sluice was identical to the sluice to which the abandoned eastern canal was connected.

As the northern part of the canal bund is restored, the close command area is much changed by activities of new settlers. We were not able to trace the beginning of the canal on the ground either in 1988,1990, or 1992. In 1992 we lost track of the canal about 1.1km north-west of the Vavalavava bund. The contour mapping recently earned out by the Survey Department was not able to depict the beginning of the canal bund either.

This lack of evidence is a problem since there is a reference

by H.L. Moysey, in his field survey of 1884, to two sluices from the then totally abandoned and jungle covered tank. He states that he was able to visit only one of them, but does not indicate anything about where (on the tank bund) the sluices are situated (Bell, Fernando, Moysey 1914). As the location of the ancient sluice documented by the Irrigation Department and the beginning of the canal on the topographical map con- cides, we have decided to base our calculations on the efficien

cy of the system on the height above mean sea level ascribed to the ancient sluice by the Irrigation Department plan. It should be kept in mind, though, that ground truth has not been established by the project itself.

Southern supply canal

One hundred and eighteen years after Blakesley’s initial sur vey of the Sigiri Mahavava bund, SARCP field team mem bers, guided by peasants living in the area, found that Sigiri Mahavava was connected by a canal bund continuing from the southern end of the tank to the Vegollavava and from there by a still existing waterway, termed ‘ancient irrigation channels’ in the topographical map, probably to the Mah- agona Oya. This canal could then have provided the vava with an additional supply of water without a canal connection to the Kiri Oya basin (see fig. 12:3).

post quern for the bund of the eastern canal, south of the possible connection and the western bund.

The eastern canal itself is of course one project, in the sense that it must have been built from the south northwards, always in relation to the known level of the outlet and water head of Vavalavava. Whether this took place, gradually or as one single effort, could be tentatively tested by obtaining a terminus post quern of the bund along the canal.

Three probable stages could be hypothesized:

(1) from Vavalavava up to a seasonal stream that joins from the west, now continuing through a breach to the Alakolavava tanks in the iron production area. Here the canal bed is slightly bowl-shaped, forming a local watershed to the north in the canal itself. This was probably to protect the bund from the inflow of water from the west, and to trap silt car ried by this water.3 It might also have been possible to end the canal bund here, regulating the water outlet from Vavalavava in relation to the watersupply from the natural stream. The present breach might have been the site of a sluice.

(2) from there up to a hypothesized connection to the western canal leading to Sigiri Oya,

(3) from the hypothesized canal connection northwa rds.

Regarding the Sigiri Mahavava itself, we will test the as sumption that it was built in stages. Minor streams coming up to the abandoned bund, two minor tanks which today function independently along restored parts of the ancient bund, signs of local gathering of water behind the abandoned bund, and cultural remains visible in the bundfill are cases in point.

Five different areas of possible independant functioning have been identified, together with one stretch of the bund - the midway narrow passage where Blakesley stopped his sur vey, terming it a canal - that might specifically belong to the unifying project. These initial observations will be followed up in the field by mapping, documentation of visible construc tional features and, if time allows, trenching of bunds to obtain a terminus post quern.

Study area

After the preliminary field survey, the study area was delineated to comprise Sigiri Mahavava, the possible irriga- tion/feeder supply canals east and south of the vava, the storage tank supplying the canal - that is Vavalavava, and a feeder tank ‘competing’ with the eastern canal and maybe with Sigiri Mahavava for water from the same catchment - that is Peikkulam tank. This tank mainly feeds the other side of the east-west watershed. Water from this tank ultimately flows into the Elahera canal, just south of Konduruvava (see fig. 12:1).

What the physical properties and possible datings tell us of maximum water-holding capacities in given periods and the maximum command area, could be termed the potential Va valavava and Mahagona Oya canal/Sigiri Mahavava function al history - that is, the physical limits of its yield increasing potential in given periods, and its labour investment implica tions.

Further studies

But what did this mean at the village level? How was the potential realized? The manifest functional history of the vava is of course found in the command area. To address these questions, a settlement study area could be delineated com prising the direct command area of the tank in the south and the Sigiri Oya basin up to, but not including Hirivadunnavava in the north, and the area between the Vavalavava canal and Kiri Oya (see fig 12:1). This however is not included in the present study.

Regarding the additional water supply to the tank, there are seven possible connections that could have functioned con temporaneously:

- a connection only to the Sigiri Oya basin - or to the Sigiri Oya and Kiri Oya basin - or Sigiri Oya and Mahagona Oya,

- or Kiri Oya

- or Mahagona Oya

- or Kiri Oya and Mahagona Oya - or all three at the same time.

We also do not know if all, or some of the various pos sibilities were realized at different times.

At least eight important questions have to be answered:

(1) Was there any flow of water from the eastern, Vav

alavava canal to the western, Sigiri Oya canal?

(2) Where did the eastern canal end?

(3) Did the eastern canal have the double purpose of irrigation and feeder supply?

(4) What is the time-frame for the construction of the three canals?

(5) What is the time-frame for the usage period of the canals?

(6) What is the time-frame for the construction of the tank?

(7) What is the possible volume of water that could be transported through the system, considering the va rious possibilities?

(8) How many man-days went into its construction and maintenance?

Another important question is to find out which areas could benefit from the water of the large tank and the canals. In this connection, several statements by villagers from neigh bouring villages regarding water courses from the tank, should be followed up by field surveys.

FIELD WORK SEASONS 1989-92 Village based systems

In 1989 commenced the study of present day village-based systems. The interview part of that study is now complete. The most important conclusion to be drawn from these inter views, regarding maintenance and water management, is wh at has often been pointed out in literature - namely, the possibility of maintenance and management of rain-fed village irrigation to be carried out within the limit of the village itself. An expression of this locally managed system was a former vel vidane’s statement that "the tanks have always belonged to us" (that is, the cultivating peasants in the vil- lage).

In one case it was described how a vava (Nagalavava Mahavava) was built on the villagers’ (‘the ancestors’) initia tive, but by specialized labourers from outside the village. They were called "otteruwo", and were said to have come from India. According to the tradition, they were paid in kura- kkan (PGIAR archive report Herath, Yasapala 1989/1990).

The field survey in 1989-90 corroborated this assumption of locally organized labour and management. Several aban doned vav kotu were mapped. Some of them had a known history of a "few-families-tank" in a cultural landscape con stantly changing regarding subsequent restoration, abandon ment and construction of small scale irrigation facilities.

Our attention was also drawn to what the villagers termed amuna. In this case the term designates a minor embankment within the paddy field, building a waterhead to irrigate paddy fields on a slightly higher level than the fields between the tank bund and the amuna (but naturally below the level of the tank). This way of enlarging the cultivable area is another example of a locally based irrigation technique, though of course we know nothing of its time of origin. It is a labour-saving technique, as water would otherwise have to be lifted up to the fields.

In 1990 we further documented an abandoned and miscal culated minor canal project, initiated by the villagers in the 1950s. The intention was to connect the biggest rain-fed tank of the village with a seasonal stream further south, in a then jungle covered area.

Having dug approximately 250m starting from the tank, the participants found that the water drained the wrong way, and the project was abandoned. No levelling instruments were used. According to one participant they simply dug, under the leadership of the village headman. The project was undertaken on the assumption that the land further south was on a higher level. This is true, though the difference is slight. Such a trial-and-error technique couldn’t have been used when major projects were successfully undertaken 4

Eastern irrigation and feeder supply canals

The eastern canal is built mainly along the gentle eastern slope on the other side of the watershed that constitutes the boundary of the Sigiri Mahavava’s direct catchment area. The canal would not only have brought water from the Va- valavava, it would also have gathered run-off water through its entire length. It consists of an earthen bund mainly built along slightly inclining ground. For most of its length there is thus but one constructed side; the bund material taken from what then becomes the canal bed. There are, however, st retches where a double bund could be discerned. About 2km from the ancient documented sluice, it further crosses a low sandy/gravelly ridge. Here the canal bed has been dug more than 3m into the ridge. Water will be transported and col lected on the upper side, in this case the western side, of the bund.

The bund along most of the surveyed canal was eroded and only between 0.3-lm high. A bund height of up to 2m was documented however. The canal bed at its widest was 15m.

The canal now carries water for short stretches during the rainy season, but breaches in the bund have changed the direc tion of drainage along the bund in several cases. No other constructional features such as stone lining or sluices were noticed during the survey.

Vavalavava is now restored and as discussed above, we have not been able to trace the beginnings of the canal. Instead, we started from the crossroad near Alakolavava, close to where the western canal also begins. From here we could follow the bund about 2km to the south, where it disappeared a short stretch after the major breach (see below). The field situation here is difficult owing to newly undertaken dry land cultivation, where the ground has been partly levelled by bu lldozers. Spot-height levels were taken along the present canal bed (see fig. 12:2).

Late in the field-work season in 1990, we found the con tinuation of the bund further south, but lacked the time to continue the spot-height survey. In 1992 we continued the ground survey down to ca 1.1km from the Vavalavava bund, where the trace was completely lost.

North of the crossroad, we could follow the bund only a few hundred meters, halted by the presence of elephants. Pr essed for time, we started northwards instead, from where the canal crosses the road from Polattava to Peikkulam tank. The bund was found to have been rebuilt into a tank bund (Pahalamakarayavalavava) north of the road. Soon after the (now abandoned) tank bund ended, we lost track of the bund in the jungle. Seasonal streams within the area were found to drain north-west. According to the topographical map, the bund ends about 800m east of the vava.

Because of dense scrub jungle in this elephant infested area, it was not possible, during this preliminary survey, to find the northern most part of the canal bund, to check on a probable connection to the tank or to a possible outer moat of the Sigiriya complex.

Villagers who had been doing swidden cultivation in the area north of the road, said the bund was visible for short stretches, but much dilapitated.

Our hypothesis, that this canal was used directly for irriga tion purposes, is built on the following observations:

At many places it will not be possible to use the Kiri Oya itself for directly irrigating fields to the west, as the bed is below the adjoining land.

That arable land exists below the canal is seen from the small abandoned vavas in the area, draining towards Kiri Oya, and also from the fact that part of the canal bund had been rebuilt into a separate tank (Pahalamakarayavalavava).

We further suggest that the canal was intended for irriga tion also along its southern course. As mentioned above, there is between the canal and Kiri Oya an area that must have been of great economic importance, at least during the centuries around the beginning of our era. We also suggested a site for an outlet to irrigate this area, a bowl-shaped watershed, in the canal itself (see above).

Judging by the lay of the land outside the canal bund, the watershed did not result from erosion caused by the major breach. The bund seems to have been deliberately constructed ‘down hili’, where a stream joins from the west. As mentioned above, one functional explanation could be that it was de signed to meet the inflow of water, and to act as a silt trap for the stream from the west. The bund must once have been considerably higher, for the water to ‘climb’ the watershed northwards.

We will not be able to prove the irrigation hypothesis: we can only show it to be probable. A more thorough settlement site survey in the command area of the canal would strengthen the hypothesis, but knowing the thorny, elephant infested, dense scrub jungle terrain and the available resources, this is not suggested at present.

A way of finding out if the canal was ever in use along its northern-most stretch and to obtain a terminus post quern for the construction, would be to trench the bund north of the point where the western and eastern canals might be connected. Indications of a waterflow in the eastern canal, north of this possible connection, would indicate that the eastern canal has been functioning. Other parts of the bund that are important to trench and date, are south and north of the major watershed in the canal, as discussed above.

In 1992 trenches were taken up at all three locations.5 The analyses of sedimentation phases in the canal bed however are not yet completed, hence the excavation campaigns in 1992 are to be discussed in the final report. There are, however, indications of a short time of use and neglected maintenance.

Western irrigation and feeder supply canal

The western canal bund is much shorter. Judging from the topographical one-inch sheet, it is about 1km. It begins in slightly high ground, east of a small seasonal stream, and turns east, close to the eastern canal bund. No signs of a continuation further south were seen during the preliminary survey.

It ends about 1.2km south of the Polattava village vavas. Here a seasonal stream continues, ultimately draining into the ancient Sigiri Mahavava.

We could follow the bund through the scrub jungle only for 520m before a herd of elephants approached us. It was clearly visible where we could follow it, and though it is abandoned and densly overgrown, we saw only one minor breach. From the lay of the land it could be inferred that it collects water coming from the west, and it keeps it on that side. There were no signs of water passing east to west.

Its main purpose must have been to hold the water from the stream on its western side, so that it could be brought to the vavas, and maybe more importantly, to protect the eastern bund during the rainy season.6

The important question is whether water was allowed to pass from the eastern canal to this one. Unfortunately, the field situation at this crucial point is very difficult. The Vavalavava canal bund is cut away first by the newly built road to Va valavava, directly after that by the Lenava-Alakolavava road. It is faintly visible continuing through a newly abandoned home garden. From here however it is clearly visible, running parallel to the west of the road until it turns northeastwards into the jungle. The contour survey conducted in 1992 gave no indication that the western canal was connected to the eastern one, as discussed above.

Sigiri Mahavava bund

From the preliminary survey of the tank bund, started in 1990, we have decided to divide the further study of the vava into five parts.

One concerns the northern-most part of the vava closest to the Sigiriya complex itself.7 As proved by the present situa

tion, this part of the tank can function as a rain-fed tank (Sigirivava) independently of the abandoned parts to the south.

Here, trenching of the tank bund, the tank bed and part of the outermost rampart in the vava bed, was commenced and completed in 1991. The major questions were of the relation, regarding chronology and function, between the tank bund and the Sigiriya complex.

The Sigirivava bund has recently been restored, but in 1991 there remained unrestored parts to the north and south. No traces of protective pitching of stones have been found along this northern-most part of the ancient Sigiri Mahavava bund.

It was observed that the direct command area falls partly within the area of the outer rampart of the Sigiriya complex, west of the tank.Trenching the bund at a breach in the northern-most part, it was further found that the bund has been built on cultural layers containing bricks and tiles. On top of these there are thin layers of pure sand, indicating a period of total abandonment.

Stones probably fallen from a demolished wall on the hillside were resting on the lowest sandy layer, further st rengthening the abandonment theory. They had later been built into the bund. Charcoal samples were taken from the cultural layer to obtain a terminus post quem for the construction of the bund.

Inside the tank there is a l-1.5m high earthen bund. It continues also outside the tank bed, running approximately east-west for about 2km. In the east it joins high ground, a low ridge running north-south. To the west it doesn’t come up to the present tank bund, but ends about 150m east of it. It runs almost parallel to the Eastern Precinct rampart. It was assumed that this bund at one time constituted the outermost rampart of the Sigiriya complex (Karunaratne this volume).

One possibility that was followed up in the field was that the Vavalavava canal, which according to the topographical map ends below the bund on the same ridge, might have supplied water to an outer moat held by the outer rampart.

Along the ridge running north-south, there were no signs of any watercourse or sluice construction that indicated a water supply. A possible connection must therefore be situated fur ther west. No conclusive evidence could be found, neither of a joining canal bund nor sluice. There is a breach in the rampart, but here the ground slopes steeply to the south, and that is why it seems unlikely that water could have been brought in at this point.

From what was found regarding the outermost rampart in the vava we now suggest that the canal water drained directly into the vava; if there was indeed a connection between the canal and the vava.

Following the straight line of the rampart westwards, we end up about 40m north of what is left of the higher outer rampart, in the south-western comer of the complex. This part of the rampart was trenched as a part of the Cultural Triangle Project. Comparing what was revealed of the constructional features in the trench there, and in the trench of the low bund inside the vava, we suggest that they represent two building phases. This assumption is strengthened by the fact that they wouldn’t meet if the direction of the nearly 2km long straight bund is followed westwards.

The inner moat at the southern side of the Sigiriya complex is built in sections, probably due to the ground sloping westwards. The outer moat at the south-western comer might also have been such a section.

The bund inside the vava was built on a former stream bed at its western end, where our trench was taken up. In streambed sedimentation layers below the bund, Black-and-Red Wa re potsherds and iron slag were found. Red Ware from a variety of vessel forms was found in the bundfill itself, giving the lower time limit to the construction of the bund if a more precise Sri Lankan pottery chronology could be built up.

Just to the north of the bund, decaying limestone bedrock reaches up to 0.5m below the present surface. Only 0.2m of the sedimentation layers above are from a ‘post-bund’ situa tion, as seen from the profile below the bund construction. There are no signs of a dug out moat bed. The grain size indicates sedimentation in still, or slowly flowing water.

The tank bed has approximately the same height above mean sea level on both sides of the bund. This situation makes the assumption that the bund retained an outer moat (as seen in the south-western corner of the complex) on its northern side a bit unlikely. Neither are there any signs of a canal bed. There is a 160m wide slowly rising tank bed to the north of the bund.

A test pit in front of the end of the bund yielded no traces of a bund construction. Either the bund was never extended to the west, or was completely removed when the tank bund was built.

To obtain a terminus post quem, soil samples were taken for charcoal from the layer immediately below the bund con struction. Soil samples were also taken for particle size an alyses, and for macro fossil, pollen and diatom analyses from tank sedimentation layers, and from the stream bed layers below the bund. Charcoal samples were also taken from these layers.

Preliminary conclusions - Sigiri Mahavava

There were activities in the area before the building of the outer rampart, as indicated by Black-and-Red Ware and iron slag (which wouldn’t have been moved a very long distance from the iron production site itself) found below the bund.

The outer ramparts of the Sigiriya complex seem to have been built in several stages.

The use of the land west of the tank for agricultural pur poses seems to have been taken up after the decay of the outer rampart, as the paddy fields under the tank fall within the limit of the outer rampart to the west.

The tank bund is also built after two phases of elite related structures (bricks and tiles) had been existing at the southern side of the Sigiriya rock and after the following abandonment and decay (sand layers and fallen stone wall).

South of Mapagala, the bund has a different character. The inner side of the bund is pitched with stones, and there are remains of a probable sluice construction (a nicely cut, long stone slab) in a breach in the bund. It is to this part of the vava that the Sigiri Oya flows. EVA MYRDAL-RUNEBJER

Two test pits were taken up in 1989 to date the stone pitching in relation to the Mapagala cyclopean wall, and to obtain a date after which the bund was built (PGIAR archive report, Gunasiri 1989). It was found that the Mapagala wall predates the tank bund and the stone pitching. From the ex cavation of the Mapagala wall we know that the wall was built after 306-517 CE but before 432-550 CE (Kumaradasa this volume). The former date also gives an absolute terminus post quern for the building of the tank bund south of Mapagala.

Below the bund there are several cultural layers. Black Ware and a still undated Roman coin indicates a settlement with outside connections, from a period before the present tank bund was built.

As Blakesley pointed out, there are other indications that the Mapagala wall might predate the maximum extension of the tank. The wall runs along the eastern side of Mapagala as well, though this side would have faced the tank when it was fully developed (Blakesley 1876:59).

The Sigiri Oya might have been embanked further south east, before the building of the present bund. The features of the latter (stone pitching and possible sluice, with nicely cut stone lining) however indicate a tank ‘above’ village based irrigation. The stone pitching might be a later addition. It is not found anywhere else along the bund. It might be an unfinished project to protect the bank, started when the volume of water was enlarged (the maximum extension of the tank bund and the completion of, or planning for the eastern and/or southern supply canals).

As indicated by the cyclopean wall, labour not related to the basic production and on a larger scale than would be expected of a subsistence agricultural village, had already been undertaken before the stone pitching at least was completed.

Further south, at Kayamvala, there is now a village tank made up of a reconstructed part of the Sigiri Mahavava bund. As seen from the present situation, it can function indepe ndently of the major tank. It is now fed partly by a small seasonal stream.

There is much cultural material in the present bund fill, indicating a settlement at least before the reconstruction (whi ch is modern). To find out the relationship between the or iginal bund (at the site that has proved to function independently) and signs of settlements, we will try to locate an abandoned part of the bund close to the reconstructed sec tion and take up a test pit.

South of Kayamvala, the possible water-filled area nar rows (as understood by the cartographers following the high water contour of the tank). Finally, it has more the charac teristics of a canal than a tank. This is also seen in the field. Blakesley suggested that this was a canal with the purpose of bringing water into the tank to the north (Blakesley 1876:56). We now know that the bund continues south, with a possibility of holding approximately the same amount of water as the tank below Mapagala.

From Kayamvalavava, Sigiri Mahavava has at present a low earthen bund. No protective stone pitching is visible, and no signs of sluices were seen during the preliminary field survey. The tank bund continues into a canal bund down to Vagollavava as was documented in the field season 1992.

No major stream is known to be embanked by the vava bund south of the canal joining the northern and southern part. There is one seasonal stream (now draining to Kaluagalavava) that might have been embanked before the larger bund was built.

To conclude: the following hypotheses regarding the Sigiri Mahavava are to be tested in the field and further discussed:

That there existed smaller tanks, for example embanking Sigiri Oya, Kayamvala-ala and the stream to the south before the unification of the bund into the Sigiri Mahavava.

The case of Sigirivava is to be further studied. Our hypo thesis is that the outer rampart predates the vava. There are indications from the pre-bund layers north of the bund that there is no tank sediment prior to the bund construction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Much material evidence relating to the premodem Vava- lavava and Sigiri Mahavava irrigation systems has vanished through modernisation. Without the possibility of consulting maps and archive material related to previous documentation of these systems, there would have been a much less substan tial base for the present study. These background studies were made possible by the kind assistance of the department heads and staff of the Survey Department, Colombo and the Irriga tion Department, Colombo, and the irrigation engineer and staff of the Dambulla office of the Irrigation Department. To all these institutions we convey our deepest thanks.

A special word of thanks also to the head and staff of the cartographic unit of the Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology, Colombo, who supported the field team by obtaining indispen sable aerial photographs and maps to be used in the field.

1. Technical excavation report. SARCP: Vavalavava c- anal 1992. Eva Myrdal-Runebjer. Archive report, P- GIAR.

2. Irrigation department. Matale subdivision. Vavala vava. Tank contour and dataplan. 17.12.69.

3. See for example D. Blair, cited in Brohier (1934) 1979:7 regarding the layout of canal bunds to meet adjoining streams.

4. See Leach 1961:224, 314-315 regarding an indiv idually undertaken field canal project that failed due to a similar lack of proper levelling.

5. Technical excavation report. Vavalavava canal. 1992. Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

6. I am indepted to Martha Prickett for the latter sug gestion.

7. Technical excavation report. Vavalavava canal. 1992. Eva Myrdal-Runebjer.

REFERENCES:

Bandaranayake, S., M. Mogren and S Epitawatte (ed.) 1990. The Settlement Archaeology of the Sigiriya-Dambulla Re gion. Colombo: PGIAR.

Bell, H.C.P., W.M. Fernando and H.L. Moysey. 1914. Ap pendix - Nuvaragala Kanda. ASCAR 1914

Blair, D. 1898. Report of the Topographical Survey and An cient Irrigation works in the Tamankaduwa District. As sistant Superintendent. Annexure B Administrative Report

1898. Colombo: Ceylon Government Press: B 12-B 18. Blakesley, T.H. 1876. On the ruins of Sigiri in Ceylon. Jour

nal of the Royal Asiatic Society Ceylon Branch 8.

Bray, F. (1986) 1989. The Rice Economies. Technology and Development in Asian Societies. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Brohier, R.L. (1934) 1979. Ancient Irrigation Works in Cey lon. Part 1-3. Colombo: Ministry of Mahaweli Develop ment.

Ellepola, C. 1990. Conjectured hydraulics of Sigiriya. Ancient Ceylon. 11: 169-227.

Gunasiri, R. Sigiri Mahavava. Unpublished Excavation Rep ort. PGIAR Archive. Cat. No. 1989.

Gunawardana, R.A.L.H. 1971. Hydraulic Society in Early Medieval Ceylon. Past and Present 53: 3-27.

Herath, K. and A. Yasapala. Unpublished Irrigation Study Interviews. PGIAR Archive. Cat. No. 1989/1990.

Leach, E.R. 1959. Hydraulic Society in Ceylon. Past and Present 15: 2-26.

Leach, E.R. 1961. Pul Eliya - A village in Ceylon. Cam bridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ludden, D. 1985. Peasant History in South India. Princeton: Princenton University Press.

Mogren, M. 1990. Project Strategies: Methodology and Per spectives. The Settlement Archaeology of the Sigiriya- Dambulla Region. Bandaranayake, S., M. Mogren and S. Epitawatte (eds.). Colombo: PGIAR.

Myrdal-Runebjer, E. Vavalavava Canal. Unpublished Tech nical Excavation Report. PGIAR Archive. Cat. No. 1992.

Maps:

Polonnaruva sheet G/12.

Pt.board G21/1A; G21 3A. Survey Department. Colombo. Tank contour and data plan. 17.12.69. Irrigation Depart ment. Matale sub division. Archived at the Dambulla office of the Irrigation Department.

Comments